The October Twins: Pablo Picasso and André Salmon

When the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso revolutionized art in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, his friend André Salmon, a young French poet, turned to art criticism in order to promote the new avant-garde movements. While Salmon’s reputation as an art critic increased, he used his leverage to bring attention to his pal. In some cases, it bordered on the absurd, but Salmon didn’t care. His loyalty to Picasso never wavered, even during the period Picasso refused to acknowledge their friendship.

Salmon was born in Paris on October 4, 1881, three weeks before Pablo Picasso, who was born in Malaga on October 25th. The two friends met in Picasso’s ramshackle, pest-infected Bateau Lavoir studio (destroyed by fire in May 1970 and reconstructed in 1978). The date remains in question but was probably during the early winter of 1904-5. Their mutual friend, the Spanish sculptor Manuel Hugué, known as Manolo, commandeered Salmon to Picasso’s studio/home late one evening. Salmon returned the following day and almost every day afterward, moving into the building in 1907. He met the poet/art critic Max Jacob at the doorway just before that second visit, and the two, along with poet/art critic Guillaume Apollinaire established the “rendezvous des poètes,” scribbled above the door by Picasso himself. Apollinaire knew Salmon since 1903, when the two poets founded the short-lived literary magazine Le Festin d’Esope (November 1903- August 1904). Picasso met Apollinaire in February 1905 at the bar Austin Fox.

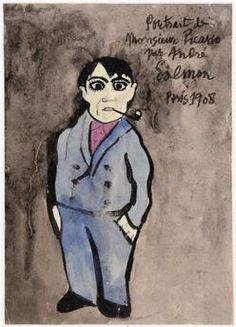

André Salmon, Portrait of Pablo Picasso, 1908 Musée Picasso. Copyright: Salmon Estate

Louis Marcoussis, The Three Poets: Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, André Salmon, 1929 Photo (C) Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jacqueline Hyde Public Domain

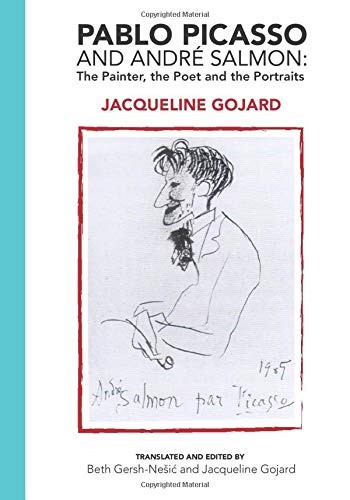

According to Salmon expert Jacqueline Gojard (Professor Emeritus, University of Paris III, Sorbonne nouvelle) in her book Pablo Picasso and André Salmon: The Painter, the Poet and the Portraits (Za Mir Press, 2019), Salmon and Picasso’s “October Twinning” established a special bond between the two within their intimate circle known to outsiders as “Picasso’s Gang.” However, Salmon was well aware of their different traits. Relying on Max Jacob’s astrological birth charts, Salmon blamed these contrasts on their respective sun signs. He wrote in memoirs Souvenirs sans fin: “October 4. Libra at 12 degrees: living in the moment, yet anxious about the future while thinking about the past. . . October 25. Scorpio at 3 degrees: A lover of solitude (even alone in a crowd), taciturn, a deep thinker . . .”

Different temperaments, true, but they also had much in common too. They were sons of artists who moved their families around to earn an adequate living. And even though both fellows chose the bohemian atmosphere of Montmartre, their families gave them a life filled with bourgeois comforts shaped by Left leaning values. Both Salmon and Picasso moved in international circles, seeking out likeminded individuals from all walks of life. Both loved poetry as well as art. Picasso retained his Spanishness while soaking up the French culture he admired. Salmon blended his brief Russian experience (with his parents and then on his own working for the French embassy, 1897-1902) to his Parisian roots, nurturing friendships among the Eastern European and Russian artists who immigrated to Paris. More significantly, as young men Picasso and Salmon thrived in their rather rough Montmartre neighborhood, but once married, they settled down with wives and property (Salmon on the rue Joseph Bara, near the Boulevard Montparnasse in the 6th arrondissement; Picasso on the Rue La Boétie, off the Champs-Élysées, in the 8th arrondissement). Then as they approached “retirement,” they moved to the south of France: Salmon died at 87 in Sanary-sur-Mer; Picasso died at 91 in Mougins.

For wives, Salmon chose an artists’ model Jeanne Blàzy-Escapette, whom he married on July 13, 1909. As a gift, Apollinaire wrote his famous poem about their wedding day, which began at the Église St. Merri, followed by a luncheon and then dancing in the streets on the eve of Bastille Day (so poor was the young couple it was the least expensive way to celebrate with all their guests). Picasso married the ballerina Olga Khokhlova on July 12, 1918 (almost three years after the death of his beloved Eva Gouel in December 1915). Their wedding took place at Alexander Nevsky Russian Orthodox Cathedral, 12 rue Daru. Apollinaire, Max Jacob and Jean Cocteau served as witnesses. Salmon attended. Both wives made great demands on their husbands which tested the strength of their friendships cultivated from the Montmartre days. Nevertheless, Salmon maintained the relationship through his visits to Picasso’s studios and writing about what he saw. It was their most enduring bond.

Much has been written about Picasso’s side of the story. Here I will explore Salmon’s perspective on Picasso, gleaned from his articles about the protean artist’s work on view in galleries or in the privacy of his studios.

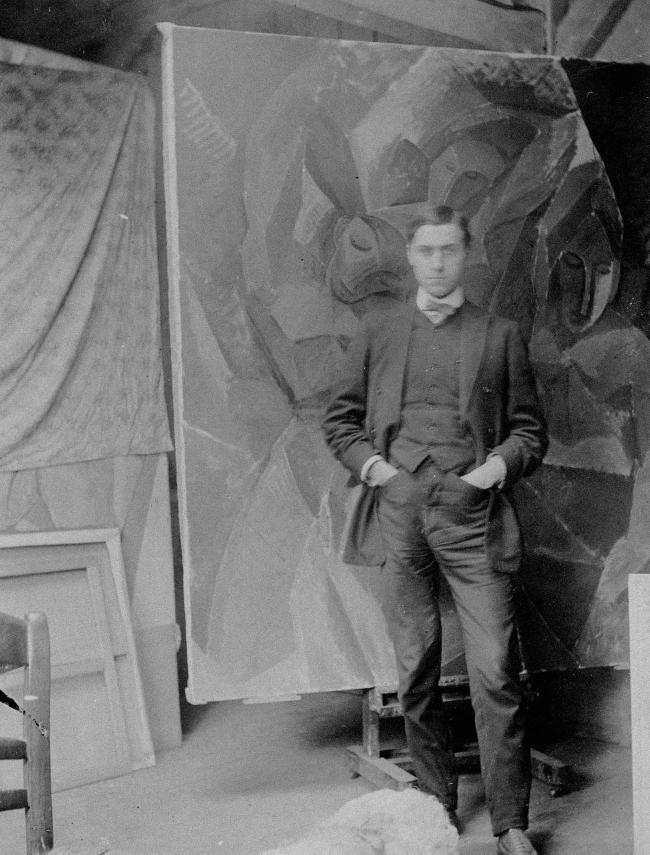

André Salmon (in front of Three Women in Picasso’s Studio), 1908

We begin with Salmon’s December 22, 1910 review of Picasso’s solo exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery, 6 rue Lafitte, Paris, published in Salmon’s daily art column “Courrier des Atelier,” Paris-Journal:

“Picasso is not one of those who is easily satisfied with himself; every day his rare secrets bring surprises, . . . Some knowledgeable art lovers admire both Matisse and Picasso. These are happy people whom we must pity.” So much for Salmon’s opinion of Matisse, whom he appreciated but did not consider Picasso’s equal.

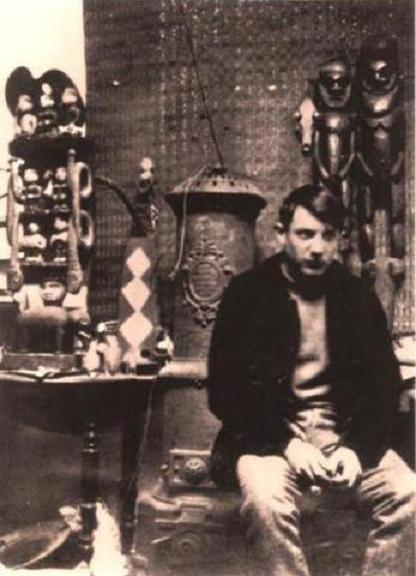

Picasso in his studio, 1908

A year later, Salmon published his impressions of Picasso’s new studio at 11 Boulevard de Clichy in Paris Journal (September 21, 1911):

“He left the Trapper’s Cabin [aka La Bateau Lavoir], perched on the hills of Montmartre, for a more conventional studio located not far from the Médrano Circus. The décor is picturesque and unexpected. Grimacing on the furniture are strange wooden figures, the best examples of African and Polynesian works. Before showing you his own artworks, Picasso wants you to admire these simple marvels. Welcoming and irreverent, Picasso dresses like an aviator. Indifferent to praise as much as criticism, he finally shows you the canvases collectors come for, and which he has the cheek not to exhibit in any Salon. Here are the colorful rogues from 12 years ago, obviously influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec; here are the beggars, the cripples, the supplicant women, all painted in blue and white, sorrowful and tragic, that make us think of El Greco; here are the Harlequins, the acrobats, and the mystical itinerant actors who revealed Picasso’s true personality. And finally, here are the most recent works that are for most people less tenderhearted. The astonishment of some art lovers delights Picasso, who doesn’t contradict them. At the most, he denies being the father of Cubism, which he simply suggested. A younger fellow asks him if one should draw feet round or square. Picasso replied with a great deal of authority: ‘There are no feet in nature!’ This fellow is still on the run, much to the amusement of his mystifier.”

Salmon’s detailed characterization of Picasso, seasoned with their preference for arcane humor, surely entertained the artist and their tight circle of friends. At the time, there was no Picasso exhibition to review. Nevertheless, Salmon decided to keep Picasso in the spotlight by enumerating, once again, his prodigious output thus far: the flashy cabaret scenes from his Post-Impressionist Period (late 19th century); the melancholic Blue Period (1901-1904); the mystical Rose Period (1905-1906); and the shocking African though Analytic Cubist Periods (1907-1911).

Salmon published his almost daily art column “Courrier des Atelier,” signed “La Palette,” in Paris-Journal from January 15, 1910 to March 31, 1912. Then he joined Gil Blas (May 6, 1912-March 31, 1914), invited by his conservative colleague Louis Vauxcelles, best known for dubbing Matisse and his followers “Les Fauves” (the Wild Beasts) and claiming Georges Braque’s 1908 paintings, exhibited at Henri-Daniel Kahnweiler’s gallery, were merely made of “cubes,” thus launching the notion his and Picasso’s work were “Cubists.”

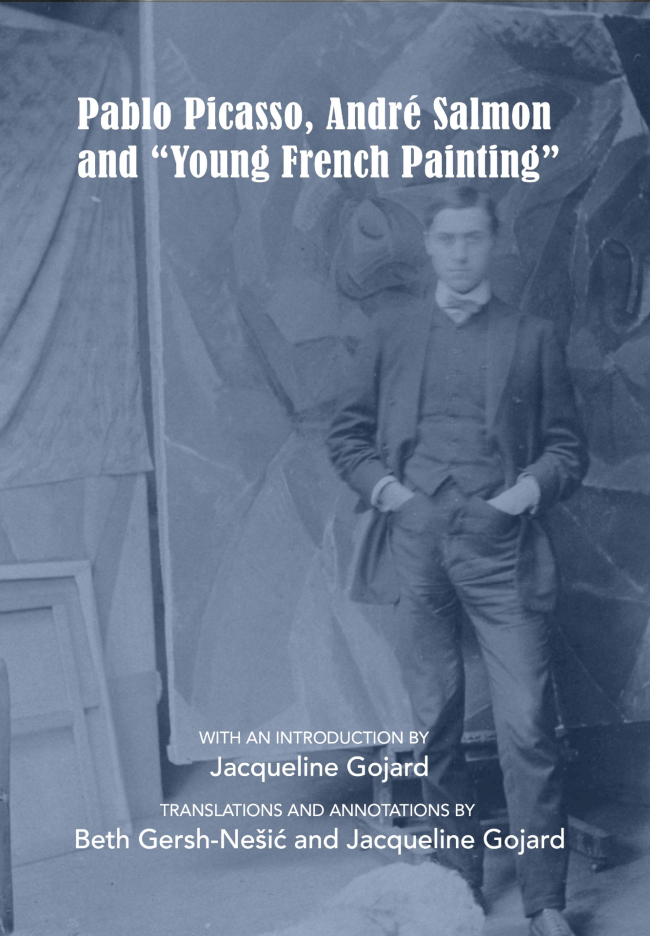

Between his stint at Paris-Journal and Gil Blas, Salmon wrote his first book on art, La Jeune Peinture française (Young French Painting), a combination of his critiques from the last two years and his concept of “art vivant,” art that begets other art through its energy. The second chapter called “An Anecdotal History of Cubism,” set down for the first time in a book a chronological perspective of the movement. Salmon’s unique insight into Picasso’s role, beginning with his infamous giant painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon benefited from his frequent visits when he lived next door to Picasso in the Bateau Lavoir in 1907. He studied the preparatory drawings and witnessed the various stages unfold. In a revised translation of Young French Painting (Za Mir Press, 2022), Jacqueline Gojard points out, in her introductory essay, the courageous position Salmon chose by claiming that this work of art, still unavailable to public eyes, constituted the foundation for all Cubist art.

Bateau Lavoir, c. 1910.

Moreover, Salmon’s description of this shocking masterpiece tried to woo an audience that knew French government officials feared this dangerous blight upon the landscape of French culture. In solidarity with these modernist warriors, Salmon judiciously appealed to his readers’ respect for self-disciple and intelligence. He invented an artist-hero on a quest for truth in art, driven by an esprit (mind and spirit) grounded in reason, rather than shallow sentimentality:

“The artist was already passionately fond of the Africans, elevating them well above the Egyptians. His enthusiasm was not based on a vain appetite for the picturesque. Polynesian or Dahomeyan images seemed ‘rational’ to him. Revising his work, Picasso inevitably would give us an appearance of the world that did not conform to the way we learned how to see it.”

That year, 1912, the two men were turning 31, and their youthful endeavors had brought them to a place of restlessness and need for experimentation. Salmon was writing poems inspired by Picasso’s collages and still working on his Manuscrit trouvé dans un chapeau (1905-1919) published by the Société Littéraire de France in 1919; Paris, Stock in 1924, and in facsimile, Fata Morgana in 1983, with a preface by Jacqueline Gojard.

In his next book on art, La Jeune Sculpture française (Young French Sculpture), completed in 1914 and published in 1919, after World War I, Salmon described a visit to Picasso’s astonishing studio at 242 Boulevard Raspail:

“I visited Picasso’s studio, when he put aside painting for an instant to construct this immense guitar out of sheet metal pieces that he believed any imbecile in the universe could assemble together as well as the artist. More chimerical than Faust’s laboratory, this atelier, which some people would claim had no art in any sense of the old term, was furnished with the most novel objects. Every object I could identify seemed innovative. I had never seen such unprecedented things before. Up to then, I did know what “new” could possibly be. Some visitors, already shocked by the things they saw covering the walls, refused to call them paintings, because they were made of oilcloth, packing paper, and newspaper. They pointed with an air of superiority at the object Picasso’s clever pains placed there, saying: ‘What is it? Does it rest on a pedestal? Does it hang on a wall? Is it a painting or a sculpture?’ Picasso, dressed in his blue Parisian artisan’s clothes, responded in his beautiful Andalusian voice: ‘It’s nothing. It’s el guitare!’

And there you are! The watertight compartments are demolished. We are freed from painting and sculpture, which already have been liberated from the idiotic tyranny of genres. It is no longer this or that, it is nothing. It’s el guitare!”

Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso and André Salmon standing outside of the Café de la Rotonde, 1916. Photographed by Jean Cocteau. Public Domain.

Less than one year later, in May 1920, Salmon presciently announced in L’Esprit Nouveau: “The life of this great artist will not be long enough to pursue all the avenues that his oeuvre illuminates. Art in the present and Art in the future emerges from his beneficial tyranny. Picasso invented everything.”

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Dora Maar), 1941 Laurent Prache Square behind St. Germaine-des-Prés Church, dedicated in 1959.

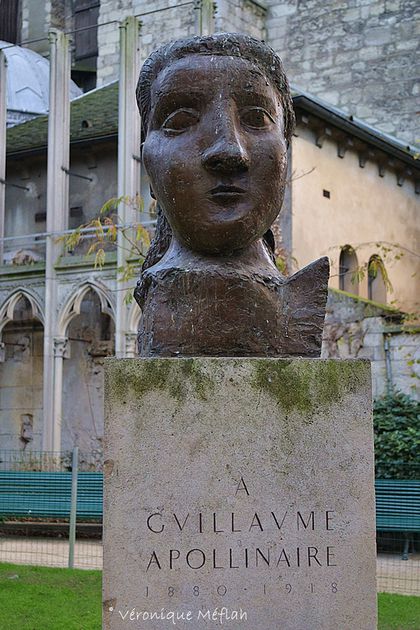

As Picasso broke ground in numerous directions for art, inventing objects and techniques unimaginable by his peers, Salmon followed him into the studio again, 11 years later, to discuss, contemplate, and understand. His essay for La Revue de France (March 1, 1931) praised Picasso’s latest direction, a soldered metal sculpture known today as Woman in a Garden (1930). It was intended for Apollinaire’s gravesite to fulfill a commission extended to him by the Apollinaire Memorial Committee (on which Salmon served). The Committee rejected it. The final choice was a bust of Dora Maar, Picasso’s mistress from 1936 to 1943, a person Apollinaire had no relationship with at all.

In this long March 1931 article, Salmon published a list of Picasso aphorisms:

“Cubism (of which he was known as the chef, resisted the title, but did not deny it either) has been explained through mathematics, geometry, psychoanalysis, etc. It’s pure literature. Cubism is its physical incarnation.”

“I don’t evolve. I am.”

“In art there is no past or future. Art that isn’t in the present will never be so. Greek art and Egyptian art are not passé; they are more alive than ever.”

Unfortunately, during the summer of 1936, their friendship hit a wall when Salmon agreed to interview the Spanish poet, writer and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno in Salamanca. The Spanish Civil War was raging. This period predates Picasso’s Guernica, completed in June 1937 for the Spanish Pavilion in the Paris World’s Fair of that year.

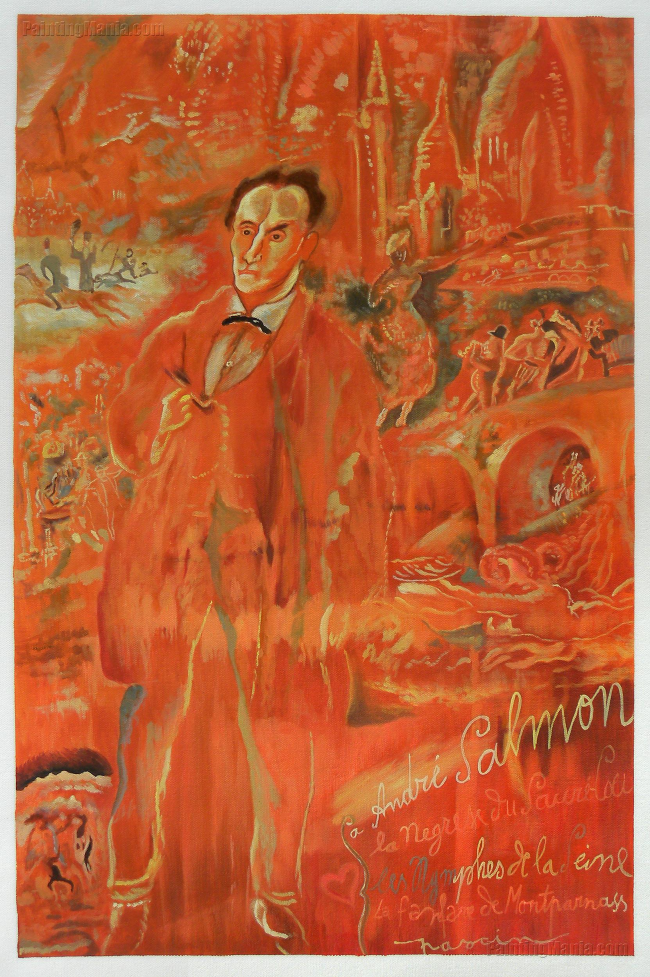

Jules Pascin, Portait of André Salmon, 1921 Oil on paper laid down on canvas Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Japan Public Domain

History tells us that Unamuno distanced himself from both sides, as Salmon’s interview on August 14, 1936 for Le Petit Parisien seems to verify: “May I ask you, Monsieur le Professor, to explain to Le Petit Parisien the main reasons that you, an indisputable leader of the Left, had joined a movement which to this foreigner is considered on the Right?”

Unamuno’s “immediate and rapid” response was: “Why? Because it is a battle for the survival of civilization over barbarity… A collective mental illness has descended upon the world. What else? I hear the respect expressed for the ideas. What a pity! First, there must be ideas that one can respect. An unhappy illiterate person ecstatically talks about Russia. I ask you: what does he know about this country, he who knows so little about his own country? … Can one truly support burning churches in Barcelona because they have no artistic value? Artistic or not, we should respect them. Now, hear me out, I want to complete this thought. I might understand invading the churches to steal from them. But burn them! Destroy them! Evil for evil.” Miguel de Unamuno continued: “There is a word in Spanish that has also entered other languages: Desperado. Alas! It’s desperation that burned the churches. Desperation from believing in nothing…”

Miguel de Unamuno died four months later, on December 31, 1936. History always claimed it was suicide. However, two researchers published in 2020 evidence that he was probably murdered by a militant fascist, posing as a former student.

Salmon accepted the Unamuno assignment because his colleague Andrée Viollis reported on the Republican side of the conflict. In her excellent book about Salmon’s journalist career, Polvere di Storia: André Salmon Giornalista (1936-1944), Marilena Pronesti, PhD, points out that Salmon refused to align with either side once he witnessed the war’s atrocities. Written in Italian, she thankfully reprinted in her scholarly book several Salmon articles and quotations in French. Dr. Pronesti and I discussed this chapter in their friendship on many occasions. We are both convinced that Picasso stubbornly held a grudge because he felt betrayed and disappointed in Salmon’s pacifist position.

What Picasso failed to consider was Salmon’s financial situation. At this point, Salmon depended on his journalist assignments, art reviews, catalogue essays, novels, and nonfiction books that, altogether, just barely provided home and hearth for his wife Jeanne, who had become an opium addict, and her mother.

Meanwhile, Picasso could easily shoulder the expenses for his wife Olga and their son Paulo (who lived on their own), his mistress Marie-Thérèse and their toddler daughter Maia, and a new relationship with the photographer/artist Dora Maar, begun in 1936 and fizzled out by 1945, replaced by Françoise Gilot. (Picasso bought Dora a home in Menerbes, Provence, which now serves as a retreat for artists and writers.) Picasso’s Surrealist friends, most notably Man Ray and Ady Fidelin, rubbed shoulders with wealthy patrons. Salmon’s entourage, the Polish artist Moïse Kisling, Aïcha Goblet, and Marc Chagall, among others, enjoyed more modest circumstances.

Salmon’s career with Le Petit Parisian began in 1928 and lasted through to the end of World War II. At the time Le Petit Parisien came under Nazi control during the Vichy Government’s Occupation, Salmon had just returned from reporting on conditions in Syria. His bank account was empty, and Jeanne lived on very little food and heat in Paris. Salmon naively believed that his art reviews had nothing to do with politics and, therefore, indicated no sympathy for the newspaper’s fascist collaboration. It was a poorly reasoned decision which led to his condemnation after World War II and five years of prohibition from publishing under his own name. (Friends who knew his true character, remembered his 1938 articles in Le Petit Parisien condemning the systematic elimination of Jews during the Nazi Occupation in Austria, provided opportunities for Salmon to write under their names in order to stay afloat financially.)

Was he a double agent? We do not know. We do know that he protected a member of the Resistance by corroborating his alibis and he hid papers for an officer in the British military, taking on the risk of imprisonment if these papers were found by the Nazis. Salmon also hid all of the Jewish artist Moïse Kisling’s works before the Nazis could confiscate them.

Tragically for Max Jacob, Picasso refused to see Salmon when he came to Picasso’s door to ask for help to rescue Max from the detention camp in Drancy in early March 1944. Jacob died from pulmonary congestion on March 5th, the next day.

Jules Pascin, Madame André Salmon, 1923. Public Domain

After illness and suffering during the war, Jeanne died on January 1, 1949, in Saint-Joseph Hospital. In 1950 Salmon met a former model for the haut couturier Paul Poiret, Angèle Myey, whom he called “Léo.” They married on October 29, 1953.

After Salmon moved permanently to Sanary-sur-Mer, he ran as a Leftist candidate for a seat on municipal council in 1963 and won. He received the Grand Prix for poetry from the French Academy in 1964, and in 1967, he became a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters.

The two surviving members of Picasso’s Gang reconciled in November 1951 when they met at the premier of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and her Children at the Théâtre de Suresnes, Paris. Witnesses say Picasso embraced Salmon and nothing more was said. The “October Twins” continued to see each other in the South of France until Salmon’s death on March 12, 1969.

Yes, André and Pablo were quite the team: scrappy, irreverent, intuitively receptive to each other’s artistic directions, and ultimately quite sentimental about their youthful days in Montmartre: “We were truly happy then,” Picasso told Salmon. As we look forward to a year of celebrating the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death on April 8, 1973, we must remember that his celebrity began with Salmon’s willingness to promote his radically new art and defend him in the face of derision, rejection, and dismissive silence.

Joyeux Anniversaire, André Salmon and Pablo Picasso, the “elders of the Bateau Lavoir.” (The final words in Salmon’s mammoth memoir Souvenirs sans fin).

For more information about André Salmon, please visit the official website.

And the André Salmon Blog.

Lead photo credit : Salmon and Picasso in Sanary, 1957, photographed by Hélène Parmelin, At the villa “Les Restanques,” rented by Hélène and her husband painter Édouard Pignon Rights of Reproduction: Jacqueline Gojard.