Art Historian Wendy A. Grossman on Man Ray’s Muse Adrienne Fidelin

Photo credit: Man Ray, Ady Painting “Le Beau Temps,” 1939, gelatin silver print, Paris, Eva Meyer Collection, © Man Ray Trust 15/ADAGP Paris 2020

The First Black Model in a Major American Fashion Magazine Was French

About a year ago, I reviewed the ground-breaking exhibition The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse, which was on view at the Musée d’Orsay from March 26 through July 21, 2019. In preparation for that review, I attended a symposium in New York organized by the curator Denise Murrell, Ph.D. during her exhibition Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, at the Wallach Gallery on Columbia University’s Manhattanville Campus (October 24, 2018-February 10, 2019), the show that gave birth to its Parisian version. At that symposium, I met the vivacious art historian and curator Wendy A. Grossman, Ph.D., who was investigating the life story of the Guadeloupean dancer and model Adrienne Fidelin. Fortunately, Dr. Grossman stayed in touch and sent me her April 2020 publication on Fidelin, available for open access on the Modernism/modernity website.

Dr. Grossman is a Curatorial Associate at The Philips Collection in Washington, D.C., and a Senior Lecturer at the University of Maryland in College Park, Maryland, where she offers courses on art history and the history of photography. Her prodigious list of publications on Man Ray, African art, photography, and the reception of these images can be found in anthologies and academic journals produced in the U.S., France, Austria, Germany, Denmark, the U.K, and other international publishers. Among the exhibitions she has curated, Man Ray, African Art and the Modernist Lens, 2009, is still available for study in her magnificent award winning catalogue (University of Minnesota Press, 2009). She has won numerous awards, fellowships and grants for her research on Man Ray. For Adrienne Fidelin, well, here she shares her experience and observations.

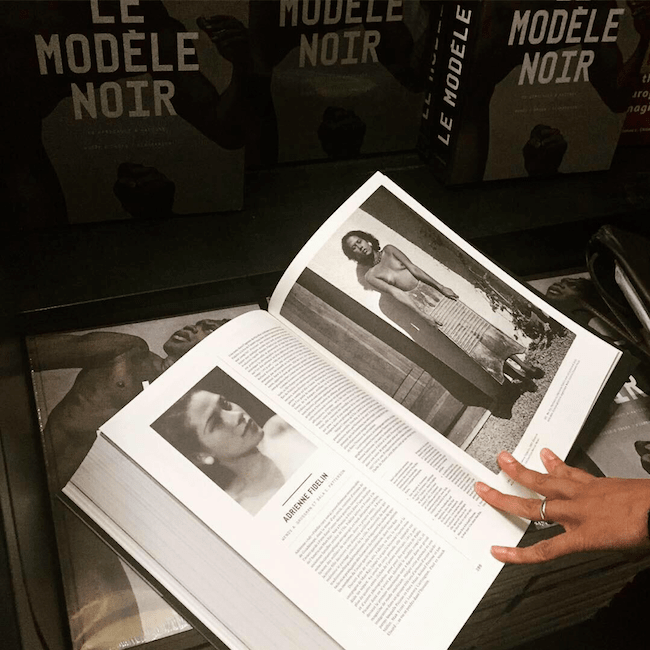

In addition to her most recent essay, Dr. Grossman’s publications on Fidelin include two collaborations with writer Sala E. Patterson: an essay for Le Modèle Noir catalogue and an entry for The Dictionary of Caribbean and Afro-Latin American Biographies (edited by Franklin W. Knight and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Oxford University Press, 2016). Dr. Grossman is at work on a book-length manuscript that expands upon these publications.

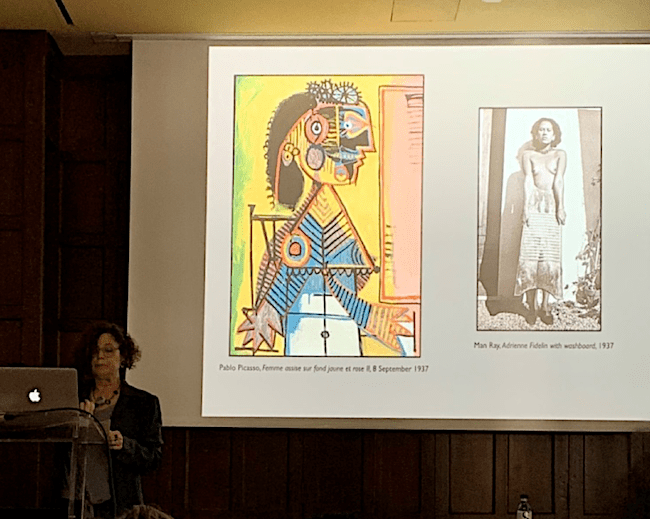

Wendy A. Grossman, Ph.D., presenting on Adrienne Fidelin’s portrait by Picasso at symposium in conjunction with Le Modèle Noir at the Musée d’Orsay, 2019.

Beth Gersh-Nešić: Dr. Grossman, you recently published an exciting article entitled “Unmasking Adrienne Fidelin: Picasso, Man Ray, and the (In)Visibility of Racial Difference,” in Modernism/modernity vol 5, cycle 1 (April 24, 2020), in which you reveal the previously unknown identity of the sitter for Picasso’s Seated Woman Against Yellow and Pink II, aka Portrait of a Woman (September 8, 1937). You convincingly argue that this is Adrienne Fidelin (1915-2004), a young dancer from Guadeloupe, who met Picasso through her current lover Man Ray.

Please tell us, which came first: discovering the mysterious Picasso portrait from 1937, the year Picasso and Dora Maar spent a summer holiday in the South of France with Fidelin and Man Ray, or your work on Man Ray, whom you have written about for quite a while now?

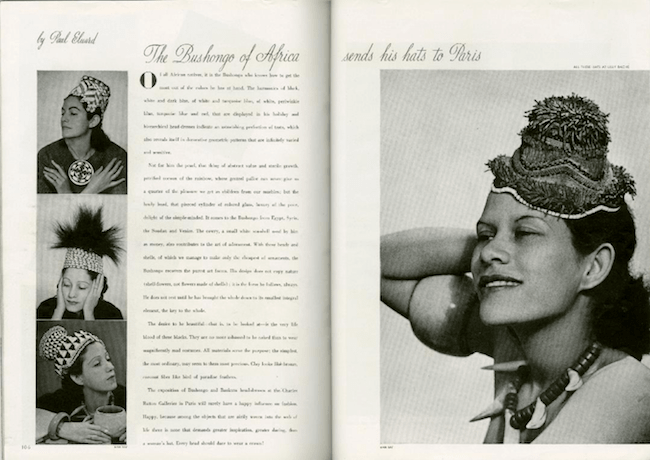

Wendy A Grossman: I was introduced to Ady, as I’ve come to know her through years of investigating her life’s story, literally through the lens of Man Ray. The starting point for my research was a critical examination of photography’s instrumental role in the transformation from artifact to art in the Western reception of African objects. This was in 1991 in the wake of the controversial 1984 exhibition at MoMA, Primitivism in 20th Century Art. As a photo aficionado, I was struck by how marginalized the medium as an art form was in that project. And intrigued by a brief passage in one of the opening essays that mentioned in passing Man Ray photographs of models sporting Congolese headdresses. Ady, it turns out, was the model most frequently featured in the artist’s so-called Mode au Congo series. One image from that suite of photographs was featured in a 1937 issue of Harper’s Bazaar, inadvertently and unceremoniously making Fidelin the first black model to defy the fashion industry’s intractable color barrier and appear in a major American fashion magazine. My curiosity about the Mode au Congo images and the story behind them launched me on a journey that ultimately led to the discovery of the Picasso painting in which Fidelin has been hidden in plain sight.

Man Ray, “The Bushongo of Africa Sends His Hats to Paris,” Harper’s Bazaar, September 15, 1937, Collection Wendy Grossman, © Man Ray Trust 15/ADAGP Paris 2020

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin photographed for Mode au Congo series, 1937, gelatin silver print, © Man Ray Trust 15/ADAGP Paris 2020

BGN: Can you tell us a bit about Adrienne Fidelin. How did she meet Man Ray?

WAG: Piecing together disparate bits of evidence to recreate Fidelin’s story has often seemed like solving a giant jigsaw puzzle. There is no memoir, significant body of personal writings, or meaningful accounts of this figure either by her contemporaries or scholars of the era. It is through the mining of correspondence, archives, genealogical sites, and the plethora of images in which she appears that her story is finally starting to come together.

Ady was born on March 4, 1915 in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe to one of the island’s oldest Creole families. The exact date she moved to France is uncertain. But we know that it was subsequent to the 1928 cyclone that devastated the Caribbean and killed her mother. Following her father’s death a few years later, she came to Paris where at least one of her older siblings was already living. She was a devotee of the vibrant diasporic entertainment scene in Paris, especially the Bal Blomet, where she was able to fuel her passion for traditional Antillean dance.

Although no evidence has surfaced to confirm that Ady and Man Ray met at one of these locales, it is easy to imagine such a scenario based on the artist’s documented involvement in that milieu. Her name first appears in his address book in December 1935. In the ensuing years before his abrupt departure from Paris in the face of the German occupation in the summer of 1940, she was a steady fixture in Man Ray’s life. He chronicled many of their adventures together in close to 400 photographs. Particularly revealing about the many roles she played in his life is a photograph in which she is seen paintbrush in hand working on one of his most famous paintings, Le Beau Temps. She is also the subject of several drawings, paintings, prints, and appears in a short film clip.

Man Ray was not alone in finding Ady an alluring model. She is an animating presence in a number of photographs by Lee Miller and Roland Penrose, both members of the elite avant-garde circle to which she was introduced by Man Ray. Beyond this circle, she was also a model for the German artist Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schultze), who was making a name for himself as a photographer in Paris in the interwar period. Evidence has surfaced that she had a fledgling film career as well.

Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson’s essay on Fidelin in Le Modèle Noir exhibition catalogue, photographed during the opening reception at the Musée d’Orsay on March 27, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Sala E. Patterson

BGN: When did you decide to investigate Ady’s story? How long have you been pursuing this research?

WAG: Ady’s story was a component of research I began in 1995 that evolved into my dissertation topic. Even as she featured in several of my publications beginning in 1996 and in the 2009 traveling exhibition Man Ray, African Art, and the Modern Lens, I was acutely aware from the onset how little was known about her. I couldn’t find even basic information about her birth or death dates. When I was invited in 2016 to write an entry on her for the Oxford Dictionary of Afro Latin American Biographies, I became determined to redress the lacuna. I joined forces at that time with Sala Patterson, a writer and equally indefatigable researcher who shared my preoccupation with this lost figure and brought her unique insights as an African American woman to this endeavor. We co-authored both the dictionary entry and the essay in the catalogue for Le Modèle Noir.

Wendy A. Grossman, Ph.D., in front of Adrienne Fidelin’s apartment door in Albi, October 10, 2018. Photo courtesy of Eva Meyer.

BGN: Did you and Sala travel to France in search of Ady? We see you in front of her apartment door in Albi, in the South of France. When did she live there? When and where did she live in Paris?

WAG: Sala and I each independently traveled to France on multiple occasions over the years engaging in our respective research. I took advantage of a trip to visit a Man Ray exhibition in Albi in 2018 to do double duty, using the opportunity to track down the apartment house where Ady lived. The photograph was taken outside the door of the apartment where she spent the last decades of her life with André Art, the man she married after learning that Man Ray had moved on during the war. Ironically, the last photos Man Ray took of his former lover were with his wife Juliet, made when the couple returned to Paris in 1947 to retrieve artwork and property, some of which he had left in Ady’s care. Although she became estranged from the avant-garde circle that had been her virtual family before the war, correspondence between the two couples show that they stayed in touch until at least 1961. She led a modest life in this apartment until her death in 2004, stories about which I was able to learn from a close neighbor who was still living there when I visited. Unfortunately, Lucien Treillard, Man Ray’s assistant in his final years, claimed in a widely circulated interview in 1998 that Ady was no longer alive, effectively short circuiting any final opportunity to track her down and hear her tell her own story.

Figuring out her various domiciles in Paris is more complicated. Census records are spotty. It is not clear where she lived when she first met Man Ray, although we do have the phone number he registered in his address book. But by 1938-1940, evidence points to her living with him in his apartment in Paris at 40 rue Denfert-Rochereau and accompanying him on regular excursions to his house in St. Germain-en-Laye. After Man Ray fled, she remained in the Paris apartment and maintained it for as long as she was able to with limited resources under the Occupation. After the war, her correspondence with Man Ray puts her first at 18 rue Wurtz, Paris 13 and then at 1 rue du commandant Guilbaud, Paris 16, for a few years before moving to Albi.

BGN: Your tireless search for the details about an artist’s model and muse who lived in Paris reminds me of Eunice Lipton’s book Alias Olympia, which recounts her search for Édouard Manet’s model and muse Victorine Meurent. You too looked through countless records, letters, documents, etc., to piece together Ady’s story. Were there any memorable moments in Paris that might give our readers a sense of your journey to learn more about Ady? What keeps you going when you hit a roadblock?

WAG: My search for Adrienne Fidelin was in many ways similar to Eunice Lipton’s search for Victorine Meurent. I, too, was challenged by the dare of my subject’s gaze. After years of encountering so many images of her, I remained perplexed as to why she had become such an obscure figure in scholarship where her presence hovered.. She is glaringly absent in accounts of Surrealism, even those dedicated to the group in which she was so warmly embraced. Likewise, she is excluded from consideration in publications celebrating the women customarily deemed Man Ray’s most significant muses. This distinction is reserved principally for Kiki (Alice Prin), Lee Miller, and Juliet Man Ray. The few contemporaries who acknowledged Ady even marginally in their writings—particularly Penrose and the British Surrealist artist Eileen Agar—reduced her to an exotic figure characterized by the color of her skin. She was a storyless character in the Surrealist drama of this circle of key protagonists in that movement. Like Lipton, I felt compelled to find and make visible this woman’s story.

One of my first stops in this journey was the Centre Pompidou, where Fidelin’s correspondence with Man Ray is housed in the Kandinsky Library. Additionally, I had an enlightening engagement with the hundreds of photographs in which she appears that are stored in the Fonds Man Ray of the museum’s photography collection. Reading the correspondence gave me a sense of her voice, while studying the photographs gave me a sense of her vibrant, uninhibited spirit and youthful exuberance. Also evident in many of the photos I encountered was the warm embrace Ady received from the community of creatives with which she became involved during the summer holiday of 1937, including Picasso.

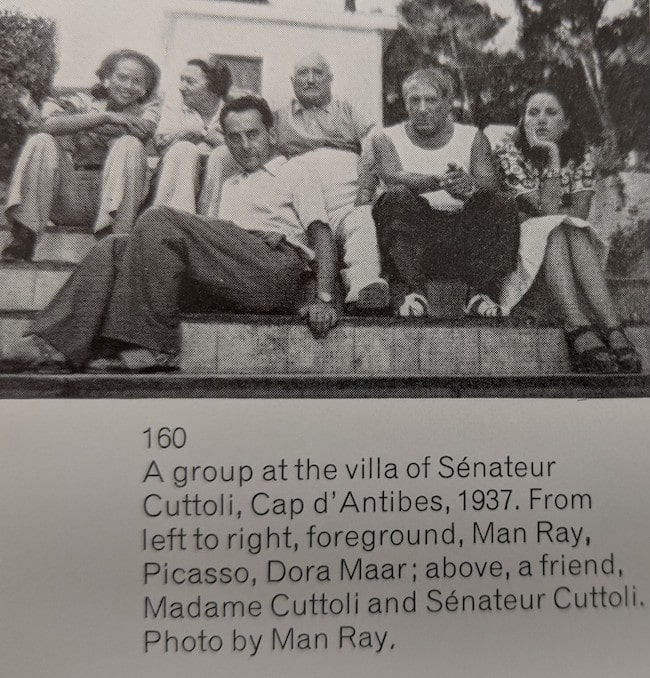

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin, Pablo Picasso, Dora Maar, 1937, Gelatin silver print, 6,1 x 8,7 cm, Collection Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI AM 1994-394 (4428) © Man Ray 2020 Trust 15 / ADAGP Paris 2020

These images piqued my interest. Armed with knowledge of the activities in Mougins that summer chronicled in these photographs, I turned my attention to Picasso’s creative output during this period, focusing on iconic portraits of fellow vacationers Lee Miller, Dora Maar, and Nusch Eluard. Despite Ady’s unassailable presence in Mougins when these other portraits were painted, she curiously never surfaced in this well-trodden territory in writings on Picasso.

It was unfathomable to me that she would not also have captured the Spanish artist’s imagination. My hunch that somewhere in the trove of Picasso’s work lingered an unidentified image of Fidelin took me to the Musée Picasso-Paris, where several breakthroughs took place. Colleagues in the archives there obliged me in my perhaps fanciful notion, helping to limit possible candidates to a handful of portraits of unattributed sitters. The minute I set eyes on a reproduction of Seated Woman Against Yellow and Pink II, I knew my hunch had paid off. While my predisposition toward finding Ady undoubtedly influenced my reading of the painting’s subject, both the racialized manner in which the figure is rendered and the composition’s striking resemblance to a contemporaneous photograph by Man Ray made the sitter instantly recognizable to me as this overlooked figure. Additional discoveries in the museum’s archives and collection records ensued: two prints of this photograph previously owned by Picasso—now in the museum’s collection—further supported my new attribution.

As for what keeps me going in the face of constant headwinds, I think on some level it is Ady herself. She has entered my psyche in ways I can’t fully explain. Images of her are indelibly implanted in my mind’s eye; it is almost as if she has leapt out of the picture frames and into my life. Pursuing her story has become an irrepressible obsession.

BGN: You noticed that Ady was photographed so often by Man Ray during their relationship, which lasted close to five years, from December 1935 to July 1940, when Man Ray went back to the U.S. during World War II. And yet, you describe Ady as “storyless.” In your essay you quote Denise Murrell’s apt remark, she was “invisible even while in plain sight.” Why do you think she received so little attention in the literature on this period in Man Ray’s life and on Picasso’s life during that extremely well-known summer holiday among the Surrealists?

WAG: That’s the million-dollar question. Clearly at play here are issues of power inequities as well as racial and gender biases that have served to determine whose stories get to be told. More than once in response to my inquiries about Fidelin to Man Ray and Picasso scholars I heard the declaration that “she wasn’t important.” One grant application evaluator for a book proposal about Ady went so far as to say they couldn’t imagine that her story would be of interest beyond a “narrow targeted audience.” This reviewer gave my application the lowest possible score, presumably knocking out of competition my otherwise very positively evaluated proposal.

From Roland Penrose, Portrait of Picasso, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971, p. 64.

© Man Ray Trust 15/ADAGP Paris 2020. Photograph courtesy of Beth S. Gersh-Nesic

That said, it is notable how little her own contemporaries revealed about her in their own accounts of this period. Even Roland Penrose, who according to his son Antony was enthralled with Ady and probably was a paramour, erased her from the narrative of his biography on Picasso. This omission is made more egregious by a group photograph included in the 1971 edition of the publication with its accompanying caption in which is she is identified only as “a friend.” In Penrose’s biography of Man Ray, she fares only slightly better, being accorded one sentence. Man Ray himself in his autobiography marginalizes the woman he affectionately called his “little black sun” in his correspondence. Of course, when he wrote his memoir (published in 1963) he was married to Juliet Browner, the woman who replaced Ady only months after he abandoned her on the heels of passionate missives about his undying love. Be that as it may, I do believe that her racial identity played a role in her invisibility and the failure of scholars to actually “see” her even as they continued to exploit images in which she appears. Art history’s implication in the devaluation of people of color is no secret. Ady’s story of erasure has countless parallels, as a number of recent exhibitions and publications have underscored, most notably Le Modèle Noir.

BGN: Your answer reminds me of how we met at the symposium for Posing Modernity in New York. I had been researching Laure in Olympia, the centerpiece of Denise Murrell’s exhibition at the Wallach Gallery. How did you learn about Dr. Murrell’s work on the black model in art history?

WAG: About a year prior to the opening of Denise’s exhibition in New York, I read something online about her project and immediately contacted her to share notes about our shared interests in recovering lost stories of black models. She was very receptive and enthusiastic to learn about Adrienne Fidelin, which led her to incorporate brief mention of my and Sala’s research in the catalogue for the exhibition. While it was too late to impact the New York iteration of the show, Denise was instrumental in insuring that Ady’s story found its way into the expanded version in Paris.

BGN: You then presented a paper in Paris on Fidelin and your discovery of the Picasso portrait during the symposium Dr. Murrell and her French team organized for the Musée d’Orsay exhibition. Could you detect a difference in the New York vs. the Paris audiences’ receptions? If so, what stood out particularly?

WAG: That is a very interesting question. The exhibition was an important intervention into public discourse on race and representation in French culture, a largely taboo topic in France prior to this event. It received wide attention, was very well attended, and apparently largely well received. It certainly garnered wide press coverage. But I don’t think I’m in a position to make a comparison about the reception for the show between New York and Paris. I was only in Paris for the symposium, which also was well attended. There was a lot of interest in my revelation about the Picasso painting, which found its way into a new entry on Fidelin that suddenly surfaced in French Wikipedia. I had the distinct impression that the exhibition was mixing things up, moving the needle one recovered black model at a time.

BGN: Your article identifying Ady as the model for Picasso’s Seated Woman Against Yellow and Pink II (1937) was published in April 2020, before the eruption of Black Lives Matter protests worldwide, including Paris, the city where Le Modèle Noir took place in 2019. When did you send Modernism/modernity your manuscript for publication? Have you reflected on the timeliness of your article and the Black Model exhibition last year in light of our current BLM movement?

WAG: Indeed, this is something I have reflected upon a great deal. In the lost and found of Ady’s story we see in microcosm the manner in which art history and its cultural institutions have been instrumental in marginalizing the history of black figures and perpetuating racial inequality. I submitted the article for review in July 2019, two months after my presentation at the symposium at the d’Orsay. I chose to publish it in the open access platform of the journal Modernism/modernity because I wanted to make it widely accessible and more quickly available than it otherwise would have been, were it to appear in a print edition of an academic journal. While the concerns of the article certainly resonate with today’s Black Lives Matter movement, I think the publication also signals the prescient nature of the two exhibitions on the black model in which this scholarship first found a receptive audience. Interest in representations of black figures in the history of art of course predates those shows; but I think they spoke to and channeled the zeitgeist in ways we are only just beginning to realize now. They also presaged many of the challenges currently facing the art world and its institutions in the shifting landscape wherein fervent issues of racial inequity can no longer be ignored. The genie is out of the bottle; recognizing the manifold ways black figures have been marginalized throughout art history and taking action to change that dynamic have become increasingly critical and timely undertakings.

BGN: Where do you go from here? Are you planning to write more about Adrienne Fidelin?

WAG: I have an ambitious to-do list on this front. My research is ongoing, as are my efforts to publish additional material in various forums. I continue to lecture to different audiences on this topic. Or at least I hope to once such activities are again feasible. My search persists to locate Picasso’s portrait of Ady, which the artist kept in his personal collection until the end of his life. It has mysteriously fallen off the radar screen since its single exhibition in Arles in 2005. This endeavor is related to an exhibition proposal I hope to see realized sometime in the not too distant future. Finally, I would very much like to see my efforts culminate in the recognition of Adrienne Fidelin as worthy of a book contract and to bring that publication to fruition.

BGN: Thank you so much, Dr. Grossman, for pursuing this significant topic. We hope that your valuable research and revelations about Adrienne Fidelin, especially her place in art and fashion history, finds its way into a luscious book or, better yet, an exhibition with an accompanying catalogue.

For more information about art historian Wendy A. Grossman and her other publications, please click here.

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY