Spotlight on Laure, Manet’s Other Model in “Olympia” in the Musée d’Orsay

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

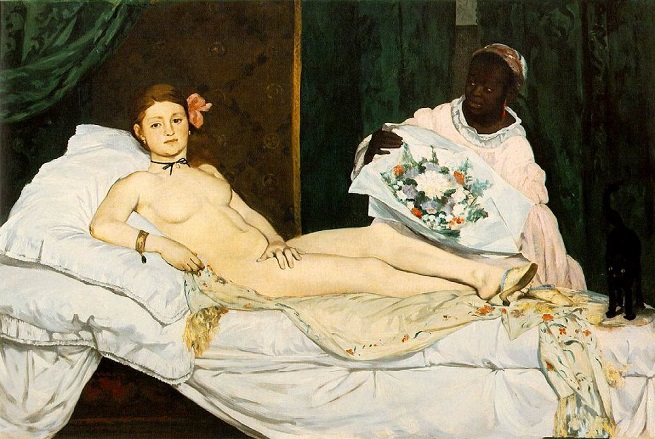

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863 (debuted in the Paris Salon in 1865)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

A few months ago, Hazel Smith wrote a superb article about Victorine Meurent, the favorite model of Édouard Manet during the 1860s. I followed up with a review of Eunice Lipton’s book Alias Olympia, which weaves together an imagined journal written by Victorine and the New York art historian Lipton’s adventures as she tracked down proof of the model’s existence. Victorine’s face and body captured the modern white woman’s claim to power through sexual congress: not only the physical but also the mental. She dared to stare with a touch of arrogance from a body unfettered by clothing (society’s armor). The best-known examples are Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia (both completed in 1863), currently on view in the Musée d’Orsay. Today, scores of pages lavish attention on this brazen red-head while ignoring her companion, the black maid who holds the copious bouquet of flowers that brighten up this severe composition. Let us now shine our light on Laure (sometimes referred to as Laura), the other model in Manet’s infamous painting of brothel life in 19th-century Paris. Her presence, along with the featured prostitute, projects the scope of modernity in Paris that accompanied Baron Haussmann’s renovations in the 1860s.

Fortunately, within the last few years, three substantial studies dedicated to Laure have pieced together her life and times: Emma Jacob, in her unpublished senior thesis for Vassar College, and Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby in Art Bulletin (December 2015). Most recently, Denise M. Murrell presented a paper on Laure during the 2017 College Art Association conference in New York City, which I had the good fortune to attend. Thanks to their work, I can write about Laure’s career in art and speculate a bit beyond their illuminating endeavors.

What do we know about Laure, this sparsely documented woman of color who posed for one of the most reviled artists in his day? In her 1999 book Differencing the Canon, art historian Griselda Pollock claims that she found a birth certificate for a woman named “Laure” dated April 19, 1839. No race or nationality is provided. If this person was indeed Manet’s model, Laure might have been born in France to parents from a Francophone region in Africa or the Caribbean. We know that she lived at 11 rue de Vintimille, in today’s 9th arrondissement, residing on the third floor (French style), according to Manet’s jottings in an 1862 notebook. This fact has been verified by a rental agreement located in municipal archives. While Laure modelled for Olympia, she would have walked all the way to Manet’s studio at 81 rue Guyot, renamed rue Médéric, in the 17th arrondissement, about 30 minutes along Boulevard des Batignolles and Boulevard de Courcelles (given this name in 1864).

Édouard Manet, Children in the Tuileries Gardens, c. 1861-2,

Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art, Providence, RI

We believe that Laure sat for Manet as early as 1861, beginning with Children in the Tuileries, 1861-2 (Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art). Some art historians claim that he met her while working as a nanny. Eunice Lipton imaged the situation differently, describing Laure as a friend of Victorine Meurent who recommended her to Manet for the painting. Another possibility may be that Laure modeled for the students in Thomas Couture’s atelier, where Manet trained from 1850-1856.

My guess is that Laure was a nanny and model for a select group of haut-bourgeois artists who knew her employers. In Children in the Tuileries, Manet placed her in a situation that seems quite familiar to an artist from the upper class: well-dressed children frolicking through the park with a governess or older sibling overseeing their every move. Children in the Tuileries seems to anticipate Manet’s larger work Concert in the Tuileries of 1862, wherein no servants (therefore no women or men of color) appear within our point of view. The difference between the two paintings marks the difference in social occasions. Daily romps in the Tuileries would be supervised by babysitters, whereas concerts offered social networking. The fashionable clothing tells it all.

In Children, we notice a slender black tree separates a black nanny and her young charge from a group of well-dressed bourgeois children who walk in unison with their backs to the audience, overlapping in white pleated frocks like modernized Greek muses. They are female and harmonious, connected by gender, class and painted surfaces. On the other side of the tree, Manet’s integrates Laure’s soft pastel pink dress into the creamy pyramid of her little client whose sprightly cocked hat is rendered simply in black and brown—a brown that blends into her nanny’s exposed arm. In paint and in life, Manet shows us that they belong to each other. Aware that the central group of girls commands the viewers’ attention, Manet cleverly enlivened the right edge with Laure’s deep rose-colored turban, saving her from pictorial oblivion. What might we glean from this decision? Is Laure a social indicator (a “marker” art historians tend to say these days)? Yes, she conveys an aspect of Manet’s interpretation of urban modernity: the park, the fashionably dressed occupants, and the influx of non-white immigrants into the community, bringing into the homogenous character of France this new element of diversity. Iconographically, Laure’s separation from the group reminds us that the new “post-slavery” black in France may seem integrated into modern Paris, but she is still marginalized and not fully assimilated into French society, despite her western clothing.

Édouard Manet, Laure (aka La Négresse), 1862-5

® All Right Reserved / Pinacoteca Gianni e Marella Agnelli

A Negress, also known as Portrait of Laure, 1862-5 (Pinoteca Giovanni e Marcello Agnelli, Turin) may be a preparatory sketch for Olympia’s black maid or a genuine attempt to individualize this “beautiful negress,” as Manet remarked in his notes. Here Manet studies Laure’s face, struggling to apply the right tones to her dark complexion. Her red, green and yellow turban sings out among the somber hues, drawing attention to the colors associated with Africa. Therefore, she becomes a type, a curiosity, like Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1685, Maurihuis), here recast in contemporary Paris instead of Delft, Holland. The comparison is not too farfetched. We see Laure’s prominent shiny earring, like the one Vermeer chose for his unknown model. We know that Vermeer’s fame surged around 1859-66, as the critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger, who appreciated Manet’s work, prepared the first catalogue raisonnée on this hitherto little known Dutch Master. Vermeer’s famous blue-turbaned young lady belongs to an artistic category called “tronies,” studies of unusual physiognomies or ethnic types in society. A tronie is not a portrait that records an individual’s identity. Manet’s seems to treat Laure like a tronie, a novelty, who offered a challenge to his artistic repertoire. The choice had nothing to do with equalizing the status of non-white and white French sitters. Manet’s paintings consistently confined women of color to situations this artist deemed appropriate for their race, class and gender.

Jacques-Eugène Feyen, Le Baiser Enfantin/Baby’s Kiss, 1865, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

In the same Salon where Manet’s Olympia made its debut, Jacques-Eugène Feyen’s Baby’s Kiss also appeared in public for the first time. Shelden Cheek identified Laure in Feyen’s painting, which depicts an Alsatian mother (in regional dress) with the family’s nanny, encouraging sibling love between an infant daughter and toddler son. Laure’s bold red shawl and blue frock contrast with the sober Alsatian clothes. Her mustard yellow headscarf seems Creole here, framing her merry eyes and amused expression. While the mother encourages this awkward exchange, Laure’s character plays along, powerless to do anything other than keep the little tike on her lap and surrender to her employer’s volition.

We know that the life of a woman of color, who was born in Africa or the Caribbean or to immigrants already living in France, suffered from limited possibilities for employment. The images of Laure and other black women in modern art offer a glimpse of their professional circumstances as maids, wet nurses, nannies, and servants, who were often treated like slaves. Even though Louis X outlawed slavery in 1315, the government rarely enforced this practice among French merchants who profited from it elsewhere. In 1794 slavery was abolished in all France’s territories and possessions. In 1848, slavery was abolished in France’s colonies as well, thus the image of a “free” black person in society entered the visual vocabulary of French art by the 1860s. Olympia’s black maid demonstrates this trend.

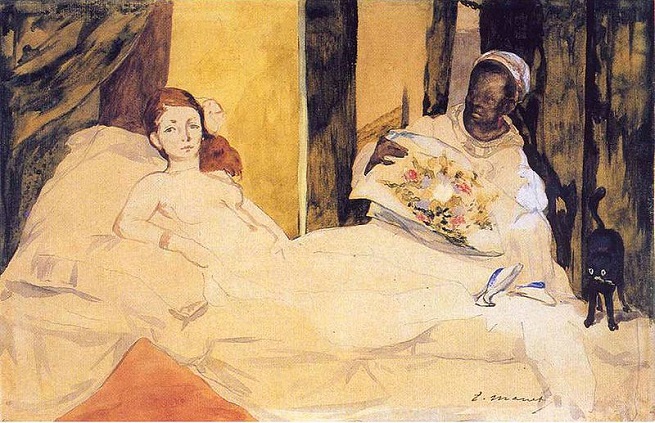

Édouard Manet, Olympia, watercolor study, c. 1863-5, private collection

Nevertheless, Laure’s servile position in Olympia reassures the viewer about social norms among the classes and people of color. The watercolor study of Olympia, which postdates the finished painting, reaffirms Manet’s intentional mapping of the prostitute’s relationship to her black servant, who verifies Olympia’s status within the pecking-order of her profession. Although this display of a courtesan captured in the act of receiving her client shocked polite society in the 1865 Salon, the accessorizing of her servant did not shock at all. In this version, the freshly offered flowers lightly dot the surface with their red, green, white and blue, transitioning the bodies from Laure in her pinkish cream dress to Olympia’s chalky white legs and shawl. The light pink of Laure’s dress matches Olympia’s linen, thus connecting the two women to each other.

Some art historians see the bouquet as a symbol that unites the two women, hinting at a relationship between two – a bit titillating and deliciously subversive along with the rest of the narrative. Other scholars have noted that the women and flowers represent the materialistic aspect of Realism, its bourgeois origins that satisfy a consumerist mentality. For both the women and the flowers are subject to a commercial transaction; they are bought and sold.

The presence of a maid also indicates the price-range for this establishment. Notice the embroidered Kashmir shawl in the Musée d’Orsay’s masterpiece, conspicuously arranged underneath Olympia’s child-like petite body. This coveted gift spoke to the viewer of wealth and status. For he who knows that a woman desires this kind of token of affection could well afford to offer it in exchange for sexual favors. The assistance of a maid confirms this assumption: this licentious setting is not a flee-bag joint. Olympia is either in an exclusive maison-close where the prostitutes had their regular customers or in her own private apartment. Most upper-middle-class male spectators caught Manet’s drift and probably wished the artist hadn’t so blatantly directed these codes toward their apprehension.

François-Léon Benouville, Odalisque or Esther, 1844

Musée des Beaux Arts, Pau

However, Olympia is not only about contemporary sexual mores. It is also about contemporary art conventions. Directing his critique toward traditional academic themes, Manet’s deliberately depicted the black and white female ensemble that often appeared in Orientalist paintings. Orientalism was the Western artists’ interpretation of Middle Eastern subject matter. To understand the “norm,” we might consider Théodore Chassériau’s Esther Preparing Herself to Meet Ahasuerus, from 1841, which belongs to the Louvre. Here we see the contemporaneous concept of racial types: an Arab, a Jew and an African (supposedly the eunuch Hagar). Esther, the Jewish heroine who passes for Persian in her book in the Bible, is understood as a racial type in 1840s Paris, here “passing” as a white notion of French beauty. Surprisingly eroticized for this biblical subject, Chassériau demonstrates the commonly held stereotypes imposed on people from various backgrounds. Chassériau himself was of mixed race, a Créole from Hispania, today’s Dominican Republic. We might also consider François-Léon Benouville’s Odalisque or Esther of 1844, which may have influenced Manet’s Olympia. Both Benouville and Chassériau exoticized and eroticized the Jew as well as the Black in their respective paintings, in keeping with their fellow Orientialists’ racist perceptions.

France’s concept of racial types was based on their imperialist position in the Middle East. Moreover, Orientalist art served as a popularized version of these exotic regions for most French audiences. Laure in modern Western dress turns this Orientalist motif into a contemporary Parisian scene and becomes another symbol of a rapidly changing Paris, now invaded by immigrants from France’s global colonies. Thus, the painting Olympia ruffled the feathers of French nationalism. Also, like Feyen’s Baby’s Kiss, it teamed up a black woman and a white woman in the act of collusion. However, in Manet’s case, the narrative was not benignly adorable, but, to everyone’s horror, unspeakably vulgar!

Frédéric Bazille, The Negress with Peonies, 1870, Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France

In response to Manet’s modernized Orientalism, Fréderic Bazille painted three much less controversial works that include women of color. We might wonder whether Laure posed for these paintings as well, since Bazille and Manet knew each other before Bazille tragically perished in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. We have no evidence that conclusively provides an answer. My gut feeling is that Bazille worked with another black model, who looks very different from Laure. (I mention these paintings to encourage you to see the Bazille retrospective at the Musée d’Orsay, a rare occasion to study his small body of work in one venue, on view in Paris through March 5, 2017.) In Bazille’s paintings of The Negress with Peonies (1870), the title identifies her Otherness. She is still an exotic type in society. Her headscarf seems to indicate she has a foreign background. She seems to be a servant arranging flowers in someone else’s home, just as Olympia’s maid takes the flowers from us, the client in order to arrange them in a vase for her mistress. Then, compare her activity to Edgar Degas’ Woman Seated Beside a Vase of Flowers (Madame Paul Valpaçon), completed in 1865 (Metropolitan Museum of Art), where a lady of leisure performs her privileged position as simply ornamentation. Perhaps, this painting also inspired Bazille’s composition. Now consider Bazille’s La Toilette (1870), which makes the servile position of a black woman quite clear. All three paintings remind us that the presence of black maids in mid-to-late nineteenth century French settings portrayed the look of modernity within the artists’ own milieux, but rarely – if ever – characterized women of color as equals in society.

Our spotlight on Laure is not complete. Denise M. Murrell’s exhibition Posing Modernity is scheduled to take place at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Gallery, Columbia University, in 2018. Therefore, consider this limited investigation a promissory note to return to the subject of Laure and “sisters” in French art within the not-too-distant future.

Frédéric Bazille (1891-1870): The Youth of Impressionism, Musée d’Orsay through Sunday, March 5, 2017. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., on view from April 9 to July 9, 2017.

Frédéric Bazille, La Toilette, 1869-70, Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Lead photo credit : Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863 (debuted in the Paris Salon in 1865) Musée d’Orsay, Paris

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY