10 Things You Must See in the Musée d’Orsay

Before embarking on a visit or treasure hunt at the Musee d’Orsay, I like to salute the exquisite edifice housing the world’s most important collection of Impressionism. Built in only two years (for the 1900 Universelle Expo), the Orsay was only a train station until 1939 (its short platforms being barely big enough for suburban commuters). During WWII it was the postal depot for POWs, then it made a brief cinematic foray (Orson Welles filmed Kafka there). Then it was temporarily home to Drouot, Paris’s oldest auction house, while they were building their permanent home in the 9th arrondissement. The western façade, where the museum’s current entrance is, was a hotel for a long stretch.

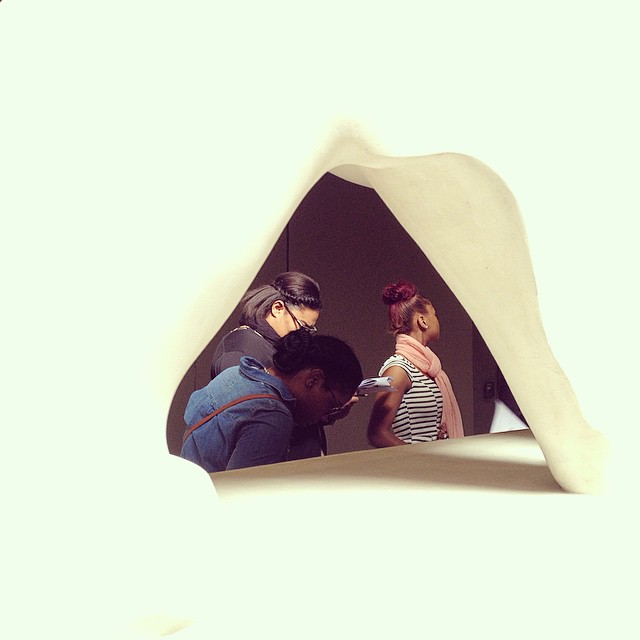

Between each of these incarnations, the building was frequently at risk of being destroyed, with many a valiant preservationist fighting developers (and the city) tooth and nail. Finally in 1986 Mitterand bought it, in order to showcase the art, chronologically, where the Louvre – viewable across the Seine – lets off in the mid-19th century. With photography recently allowed (thanks to a Fleur Pellerin, Minister of Culture, gaff), don’t neglect to focus your eye through the lens of the magnificent clocks overlooking the Right Bank. For those with limited time, here’s a round-up of the top 10 masterpieces you must see in this world-class art museum.

Closed Mondays, open until 9 pm Thursdays, all other days 9h30-6 pm; full-price admission 14€

Edgar Degas, Small Dancer Aged 14 A founding member of Impressionism, Degas was a self-described “Realist”. This celebrated version of Marie (a ballet student at Paris’s Opera) is made of bronze, but the original — which Degas exhibited in the much-criticised Impressionist Exhibition of 1881 — was sculpted in a skin-colored wax, dressed in real fabrics and topped off with real hair tied with a ribbon.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass Any PR maven knows that the best publicity is bad publicity. Manet calculated every inch of shock factor that this painting unleashed; the large canvas (reserved for important historical subjects), roughly painted background lacking any depth (is that woman floating or bathing back there?) and unrealistic shadow-less photographic light were all screams for attention, let alone the risqué subject! Sealing his rejection from society (he exhibited it in the 1863 Salon des Refusés), Manet made the subjects close to him (the two men are his brother & brother-in-law, and the nude has the body of his wife and head of his favorite model). Parodying Raphaël, Giorgione and Titian (painters the Beaux-Arts coveted), Manet received his hotly-deserved spurn from Redon, Proust and countless others.

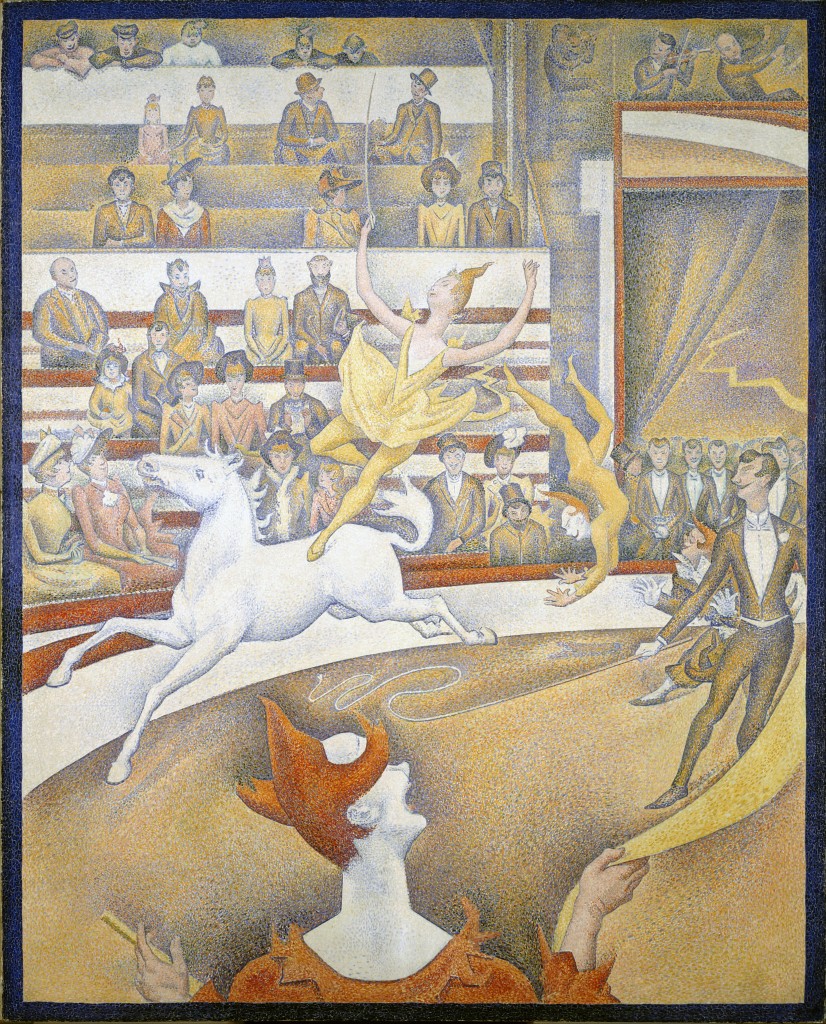

Georges Seurat, The Circus – Two spaces in this famous example of pointillism are juxtaposed: First we have the foreground including the stage for the circus-act which are all curves, stylised arabesques and spirals, filled with dynamic tension and flamboyant motion or even imbalance. Contrast this with the space for the seating and public, which is rigid, orthogonal, motionless, strictly geometrical– and you have a compositional jamboree for any Art Historian (which is why this landmark Musee d’Orsay is studied in any Art History 101 class!).

Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette – Renoir exhibited his Butte Montmartre dance garden scene at the 1877 Impressionist Exhibition. This portrayal of popular Parisian life, with its innovative style and imposing format – a sign of Renoir’s ambition – is one of the masterpieces of early Impressionism.

Hector Guimard, Banquette de fumoir – Father of the Paris Metro Art Nouveau entrances, Guimard was big on architecture and furniture being seamlessly one (a point that Frank Lloyd Wright later develops). This pretty smoker’s banquette is characteristic of the Art Nouveau use of plant forms – often with table-legs like trunks sprouting supple branches or arms of chairs crawling away like sneaky, slithering vines!

Gustave Courbet, Origins of the World – The Musée d’Orsay maintains that Courbet’s painting escapes pornographic status based on the fact that he claimed descent from Titian, Veronese and Correggio (the golden, amber color of her hair, the sensual brushstrokes, etc). Pornography or not, its owners are of interest: Commissioned by the Turkish-Egyptian diplomat Khalil-Bey, a flamboyant Paris Society dandy who had an ephemeral, but dazzling art collection celebrating the female body. A later owner of note was the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. How appropriate is that? From playboy to shrink! If any of Lacan’s patients were ever lost for words, I guess they could always discuss the Origins of the World.

Claude Monet, La rue Montorgueil, à Paris. Fête du 30 juin 1878 Choosing only one Monet from the MO’s collection is hard – so many are just so important – but this patriotic scene embodies both France and Impressionism well. The impressionist technique, with its multitude of small strokes of color, suggests the animation of the crowd and the wrist-action of omnipresent flag-waving, as well of course as the quick stroke. With the distanced vision of an urban landscape by a reporter observing the hoi polloi from above. A completely kinetic reportage.

Auguste Rodin, Fugit Amor The famous Balzac – also found at Vavin in the 6th arrondissement– is tough competition for a spot here, but the writhing, small bronze Fugit Amor wins out based on the fact that it’s part “The Gates of Hell”, the biggest project of Rodin’s life. He never finished the monumental 186-figure work (illustrating Dante’s Inferno), despite working on it for more than 20 years. This fact more than likely left him a tortured soul, much like his subjects.

Van Gogh, Starry Night Hailing from Holland, Van Gogh didn’t begin painting until his late 20s (formerly he’d been a miner’s priest as covered recently in The Washington Post), completing many of his best known works in the last two years of his life before his suicide at age 37). In this decade he produced more than 2,100 works of art, frequently painting the same scene over and over, such as this Starry Night, as seen from Arles, where he lived from 1888-1889.

François Pompon, Polar Bear An emblematic Musee d’Orsay piece, the Polar Bear brought Pompon late recognition, aged 67. He’d been the most sought after assistant in Paris, hewing blocks of marble for Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, spending his spare time in the 18th century zoo in the Jardin des Plantes. Exhibited in the 1922 Salon d’Automne, Pompon said of his animal-focused works, “I keep a large number of details that will later go” in order to get to “the very essence of the animal”. Colette was struck by the “thick, mute” paws of his animals.

Lead photo credit : © Daisy de Plume, exterior with Seine

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY