Musée d’Orsay: From a Train Station to a Museum

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Exactly 150 years ago, a group of artists, struggling and hardly known, organized into what was briefly called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, Etc. What they had in common was their new radical style and their exclusion from the annual Paris Salon. These 30 rebellious artists launched their own public exhibition on April 15, 1874, at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, in the studio of photographer Nadar. This is the moment Impressionism was born.

Only a few of the original group of independents are remembered, but the canon of Impressionists – Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Sisley and Cezanne – left an indelible mark. Their exhibition would be viewed by 3,500 curious attendees, some appreciative, others, less so. Today their canvases entertain a yearly audience of 3 million.

To celebrate, the Musée d’Orsay, the world’s largest collection of Impressionist masterpieces, is launching a major exhibition, “Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment,” which opens on March 26, 2024. The exhibition will be focusing on those very works displayed in April of 1874 juxtaposed with works shown at the Paris Salon of that year.

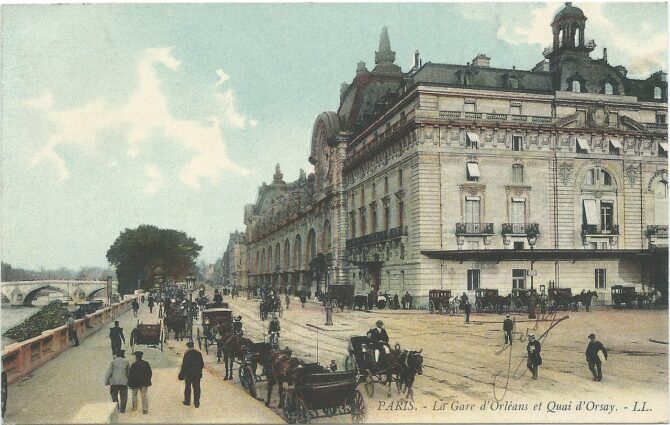

Gare d’Orsay tracks. Photo: Unknown author/ Wikimedia Commons

The works of Impressionists could not be shown to such effect had not the Gare d’Orsay – a train station – been turned into the world famous art museum it is today. Before 1986, the works of the Impressionists literally hung all over the Paris map. Some works were stored at the Louvre; many were at the Musée Luxembourg; and the Musée du Jeu de Paume was crammed with their works.

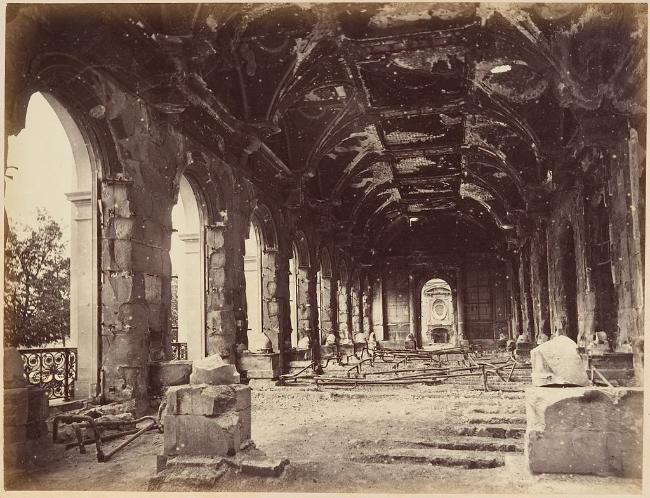

When the Musée d’Orsay opened in December 1986, 47 years had passed since the building welcomed trains. Historically, the French government had problems finding a raison d’etre for this Left Bank site. In 1840, the Palais d’Orsay was built on the Seine to house courts and administrative offices. It was torched during the Paris commune of 1871.

The burned ruins of the Palais d’Orsay. Photo: Unknown author/ Wikimedia Commons

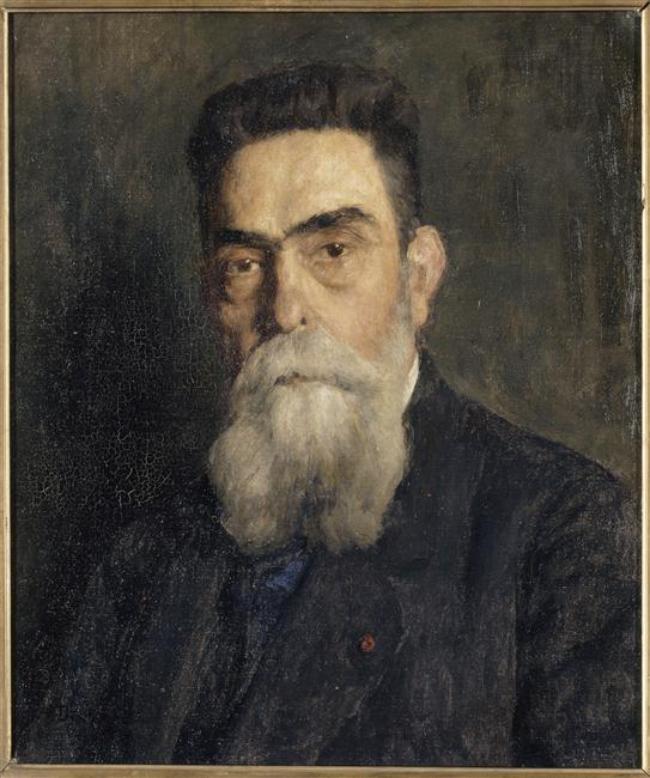

Though other ransacked government buildings were immediately reconstructed, it wasn’t until 1897 that the Orleans Railway Company received government approval to build a train station on the long-vacant d’Orsay site. Their aim was to extend rail lines into central Paris. Architect Victor Laloux designed a monumental rail terminus with a façade that harmonized with other Left Bank edifices; palaces and hotels particuliers designed in the Neo-Classical or Beaux-Art style. Originally named the Gare d’Orleans, it was the first station in Paris to receive electrified trains, and was inaugurated on Bastille Day, July 14, 1900, just in time for the Exposition Universelle.

A tasteful façade of large limestone blocks concealed the building’s industrial purpose. The building included the 370-room Hotel Palais d’Orsay on the building’s western and southern sides. The complex was a great success but Laloux and his team left no wiggle room for future advances.

Portrait of Victor Laloux by Adolphe Déchenaud. Public domain

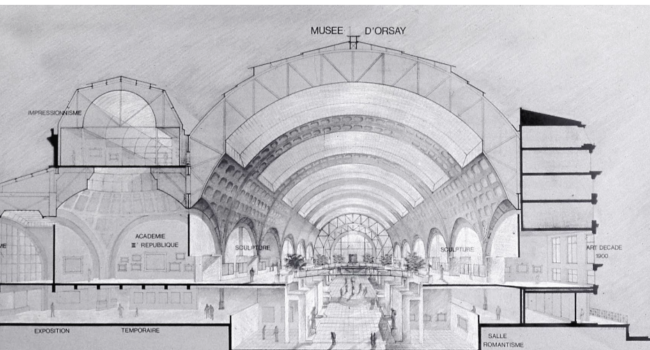

Victor Laloux, Gare d’Orsay, coupe transversale, 1898. Don Société Asturienne-Pename, 1987. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Though conveniently located, the inside tracks couldn’t accommodate longer intercity trains. By 1939 mainline trains no longer used the Gare d’Orsay, terminating instead at the Gare d’Austerlitz, an inconvenience that the Gare d’Orsay was built to resolve 40 years before. Rendered practically useless, the terminus became a stop on the RER line and storage for city trains.

Seriously underutilized, the space housed a miscellany of things during its fallow period. Part of it became a parcel-shipping center during World War II. In 1945 French POWs were welcomed back home in the expansive main hall. The auctioneers Drouot used it while their permanent premises were renovated. Orson Welles and Bernardo Bertolucci used the soaring space as a backdrop in their films. The Renaud-Barrault theatre company made it their home-base during the 1970s.

Suburban trains at the Gare d’Orsay. Google Arts and Culture.

Meanwhile, the government was entertaining proposals to permanently replace the station with either an airport, a school of architecture, or yet another government ministry. However, it was a proposal for a bigger, grander hotel on the Gare d’Orsay’s site that was finally accepted and plans were made to demolish the station. However, Parisians didn’t want a commercial hotel to dominate this stretch of the Seine.

In Paris there was a groundswell of support for the conservation of historic buildings. The 19th-century iron pavilions of Les Halles site had recently been leveled, only to be overlooked by the modern multi-colored tubes of the Centre Pompidou. It was feared that the Gare d’Orsay would be replaced by a modern/ugly building that wouldn’t complement its surroundings. This dissension forced the government to rethink its plans to demolish Laloux’s building. In 1973, the Gare d’Orsay was no longer slated for destruction, but instead vaunted as a historical monument.

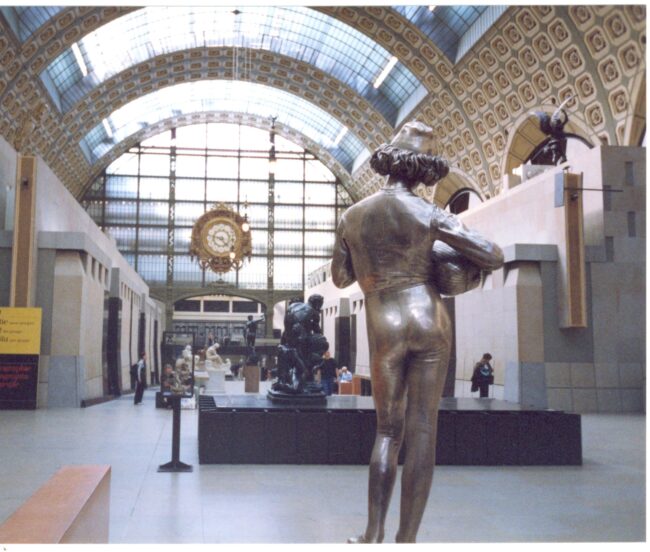

Main hall of the Musée d’Orsay, Photo: Ana Paula Hirama/ Wikimedia Commons

The French government was dealing with overcrowding at the Jeu de Paume. Housing the world-famous Impressionist collection, the Jeu de Paume had the highest number of visitors than anywhere in the world – 750,000 a year – and the highest number of visitors per square meter than any other museum.

The Louvre couldn’t relieve these excess numbers – although it had 19th-century art in its inventory, space was at a premium. The Centre Pompidou, was a no-go; its focus was 20th-century art. The chief curator of the Louvre, Michel Laclotte, had an epiphany while crossing the Seine. Of course! The Gare d’Orsay could be a museum housing both the Impressionist collection and Academic art of the late 19th century. Laclotte proposed the creation of a new museum.

Musee d’Orsay – Clock. Photo: Hazel smith

According to Andrea Kupfer Schneider in her 1998 book, Creating the Musée d’Orsay: The politics of culture in France, the goals of the new museum were to be: “(1) to provide proper presentation of the Impressionists; (2) to provide an overall understanding of the art from the period of the post-Romantics, with which the collections of the Louvre ended, to Fauvism, where the Pompidou Centre collection began; and (3) to allow the reorganization of the museums of Paris so that the Louvre’s reserves would be shown… and the Jeu de Paume could be converted to show temporary exhibitions for which its size was best suited.”

As if they were kings of old, a project like this could enhance the power of the French president. A cabal of past presidents pushed the project further, but it was François Mitterrand who would be forever linked with the project. Mitterrand’s Musée d’Orsay project, along with the building of the Opera Bastille, the Louvre Pyramid, Cité des Sciences, and the Monde Arabe, would have critics saying that Mitterrand was suffering from a Louis XIV complex.

Exterior of the Orsay Museum. Photo credit: Daniel Vorndran/ Wikimedia commons

The contract for the remodeling was given to ACT, a young architectural design firm consisting of Pierre Colboc, Renaud Bardon and Jean-Paul Philippon. Their proposal best envisioned the space as a gallery; not treating the building as a conservation project or as a blank slate, but fusing the old and new. Within the building, restored to its former glory, the team created a pleasing and functional museum.

Charged with creating 20,000 m2 of exhibition space in the original station and the adjacent hotel, ACT designed the main body of the museum over three levels. Galleries were distributed on either side of the monumental stone passageway, which was built over the traces of the old rail bed. Remnants of the old train station exist in the stunning coffered ceiling, the gilded garlands, and the famous clock, evoking the time of the Belle Époque. The architectural design retained the 25,000 m2 glass roof that flooded the central hall with natural light.

For architect Gae Aulenti, the lighting was an important feature. In collaboration with ACT, the Italian architect Aulenti was chosen to design a unified exhibition space. Through the use of homogenous building materials, furnishings and ornamentation, and an important mix of natural and artificial light, Aulenti created an all-enveloping interior. The stonework along the central atrium is a little bit Luxor and a little bit Roman Empire. Aulenti said that if the new architecture wasn’t heavy, the art would look impermanent. Considering the need for traffic flow, Aulenti created an intimacy needed for the museum’s displays via a sequence of halls and galleries on various levels.

It took six months to install the paintings and sculptures into their new home before president Mitterrand officially opened the Musée d’Orsay in December 1986. Today it is home to the world’s largest collection of Impressionist paintings.

The 3,000 art pieces on display within Musée d’Orsay draw about 3 million visitors per year. The 1980s’ configuration of the museum expected half that. Therefore, renovations are deemed necessary. The Musée d’Orsay will launch major redevelopment work from 2025 to 2027 in order to better welcome the public. The museum will remain open during renovations. The building project will be called Orsay Grand Ouvert (Orsay Wide Open). Reception space will be enlarged, and traffic flows made more logical. A nearby resource and research center is due to open in the late 2020s.

The exhibit, “Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment,” will show unexpected parallels and intersections between those paintings in the first Impressionist exhibition and those in the rivalling Paris Salon. However, the Musée d’Orsay is always a sanctuary of Impressionism, where one can revel in one masterpiece after another in the museum’s massive collection. A bonus is that the Musée is a masterpiece unto itself.

With files from Creating the Musée d’Orsay: The Politics of Culture in France, by Andrea Kupfer Schneider, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998.

Musee d’Orsay. Photo: Hazel Smith

Lead photo credit : La Gare d'Orleans et Quai d'Orsay. Postcard. Unknown author. Public domain

More in Impressionism

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY