L’Absinthe by Degas: The Ugly Side of the Belle Epoque

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In honor of the exceptional Manet/Degas exhibition currently showing at the Musée d’Orsay, we’re taking a deeper look at one of the incredible paintings on display.

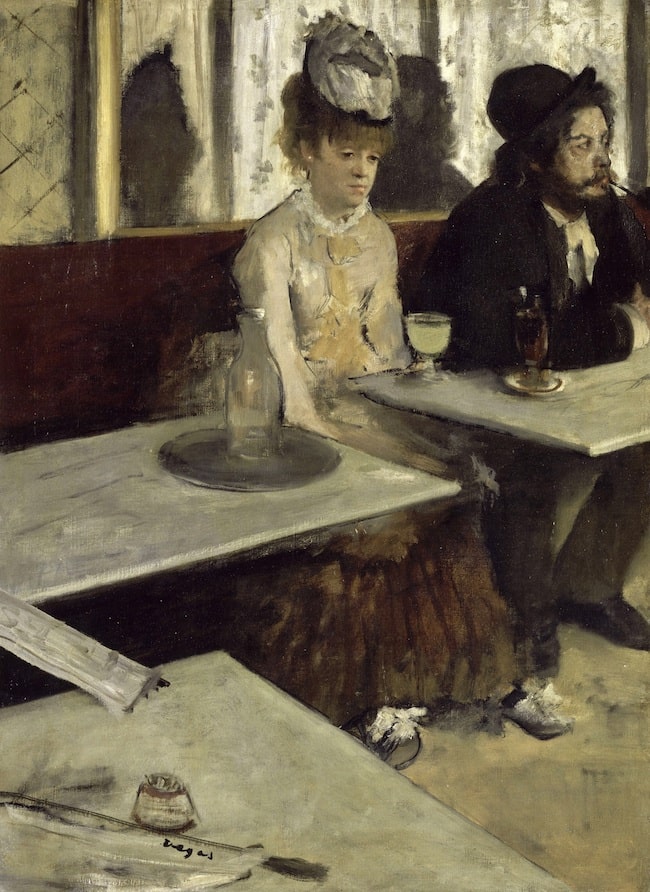

Edgar Degas painted L’Absinthe in 1875-76, in the early days of the Belle Époque, but it is absolutely not a painting which reflects the fun and glamor of that heady era. In fact, at its first showing, it was deemed so shocking that it was hidden away in storage and not shown again for over a decade. Even then, critics still railed that it was a bleak work which presented a degrading view of humanity. The story of this piece, now in the permanent collection at the Musée d’Orsay, has much to say about the less glamorous side of Paris in the late 19th century.

Originally titled Dans un Café, the painting shows two down-at-heel people sitting gloomily in a café in the early morning after a long night out. The woman is wearing quite a fashionable dress and hat, but both are shabby and her drooping shoulders and listless stare create a dismal mood. In front of her sits a glass of absinthe. The man sitting next to her, scruffily dressed in black, has a brown drink in front of him, perhaps mazagran, a cold coffee beverage which was often taken as a hangover cure. Although they seem to be sitting together, neither takes any notice of the other. Both are lost in their own melancholy thoughts and the bleak atmosphere is compounded by the painting’s colors: black, browns and greys, barely relieved by cream and small dabs of washed out green and yellow.

Edgar Degas, L’Absinthe. (1875–1876). Public Domain

The two figures were modeled by friends of Degas, the actress Ellen Andrée and the artist Marcellin Deboutin, but his depiction of them as down-and-outs, much the worse for wear, was so convincing that their reputations suffered and Degas was forced to issue a statement confirming that neither was an alcoholic. Those seeing the painting soon after it was finished would have immediately recognized the setting as the Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes, a popular café in the Place Pigalle in Montmartre which was frequented by many of the artists and writers of the day, including Degas himself. The painting was actually completed in his studio, but Degas must surely have done preparatory sketches in situ in the café.

Ellen Andrée (1856 – 1933), actrice française de théâtre. Nadar.

The painting was first exhibited at the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876 and was so disliked by critics, who called it “ugly and disgusting,” that it was hidden away for 15 years. At its next showing, in 1892 at the Grafton Gallery in London, the reaction was, if anything, worse. Critics regarded it as an affront to morality. Walter Crane, writing in the Westminster Gazette, certainly didn’t mince his words, despite a grudging recognition of the artist’s technical skills: “Here is a study of human degradation, male and female, presented with extraordinary insight and graphic skill, of squalid and sordid unloveliness, and the outward and visible signs of the corruption of society.”

This painting illuminates a side of the Belle Époque which many did not want to recognize at the time. After the end of the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris and the upheaval of the Paris Commune, there followed a 40-year period of peace in which the arts flourished and new technology improved life – for the wealthy at least – enormously. This lasted right up until the outbreak of war in 1914. But alongside those who could enjoy the carefree gaiety and glamorous lifestyle of this era, some 70% of Parisians were living in poverty. The better off, even the aristocracy, enjoyed visiting places like Montmartre, where they could mix with the working class and enjoy bawdy entertainment, but most did not spend much time thinking about the realities of life for the poor. This painting prompted them to do so and made them uncomfortable.

Olof Hermelin, Gatuscen från Montmartre, Paris, 1875

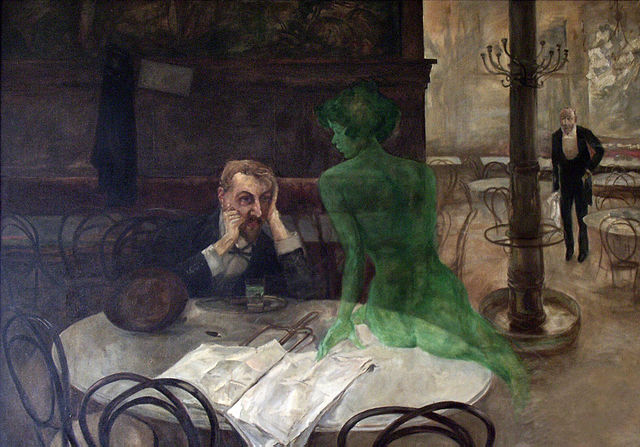

It is no coincidence that the subject matter of the painting is absinthe, the hugely popular – and destructive – drink so readily available in 1870s Paris. Sometimes known as “la fée verte” (‘the green fairy’), it was a green colored, highly alcoholic spirit with a bitter taste, diluted with ice and water and sweetened with sugar. It had been brought to France by soldiers who had fought in Algeria, where it was used against malaria and soon became well-known among the artists and writers of the day, who saw it as a spur to creativity. The poet Raoul Ponchon explained its inspirational quality, writing that “when I drink you, I inhale the young forest’s soul.” Toulouse-Lautrec was known to carry a vial of absinthe with him wherever he went, secreting it in a special little compartment in his walking cane.

Absinthe glass and spoon. Photo: Eric Litton / Wikimedia Commons

Absinthe was so popular that in the city’s cafés people referred to 5 o’clock as “l’heure verte” (the green hour), when people crowded in to enjoy it. Its consumption soon spread to the working classes who were attracted by its low price and its ability to help them blot out the misery of their everyday existence. This cheap new way to consume alcohol was especially welcome because the Great French Wine Blight of the 1870s had made wine scarce and very expensive. But the potent new drink made from wormwood leaves, originally developed by the Ancient Egyptians, proved dangerous both for individual drinkers and for society.

Grande wormwood. Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler’s Medizinal-Pflanzen. Wikimedia Commons

Absinthe fueled drunkenness because it was cheap and readily available. More seriously, it was highly addictive and caused hallucinations and its increasing popularity led to a rise in mental illnesses. In fact, some customers would order it by asking for “une correspondance,” meaning “a ticket” to Charenton where there was a well-known hospital for the mentally ill. Absinthe caused huge social unrest, as explained by a social commentator who wrote that “it makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country….”

Viktor Oliva, The Absinthe Drinker (1861–1928)

Thus, Degas had painted a comment on Parisian society, highlighting the baleful life lived by so many of its ordinary citizens, those who were not able to enjoy the fizz and glamour of the Belle Époque. There are other paintings from the era which do the same, including Edouard Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère and two other Degas works portraying the long tiring slog that was the life of the Paris laundresses of his day: The Laundresses and Woman Ironing. Émile Zola’s novel L’Assommoir, published in 1877, describes the devastating effects of alcohol on the city’s poor.

Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Public domain.

Today, we can think of this painting as adding to our knowledge of life in 19th century Paris, of showing us something of the lives of those who were not swept up in the glamor of the Belle Époque. The rejection of the painting when it was first exhibited shows that many of the Parisians who went to art exhibitions in the 1870s were not ready to think too hard about the life of their fellow citizens. And yet a few of its early viewers, such as the art critic George Moore, did understand what Degas was saying. Although he had dismissed the female subject of the painting as “a whore,” he was nevertheless willing to admit that the subject of the painting was important. “The tale,” he wrote, “is not a pleasant one, but it is a lesson.”

Related article: Favorite Paintings in Paris – L’Absinthe by Edgar Degas at the Orsay

Lead photo credit : The Absinthe Drinker, Edgar Degas (1876), Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France. Photo: Wikiart, public domain

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY