Manet/Degas: An Exceptional Show at the Musée d’Orsay

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas met for the first time in January 1862 while copying the same work of art at the Louvre. In 2023 they meet again, their art compared and contrasted in the exhibition Manet/Degas, at the Musée d’Orsay, from March 28 until July 23, 2023. And what a reunion it is.

Flanking the entrance are their self-portraits. Degas’ proper countenance balanced with Manet’s wilder impression of himself. I can imagine them 150 years ago conversing at La Nouvelles Athènes about the merits of the exhibition.

Edgar Degas, self portrait, 1855. Musée d’Orsay

Manet/Degas includes more than 100 paintings, sketches, photos and letters. The exhibition stresses the many similarities between the two artists, men of a comparable age and background, who painted similar subject matter, but it’s their differences that make the exhibition at the d’Orsay so much richer.

A little history…

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917) were kindred souls, exceptional artists inhabiting the same Parisian art scene. Both were Paris-born, educated sons of bourgeois parents, whose families wanted more for them than the life of a starving artist. However, their temperaments differed. Manet was a handsome, nattily dressed bon vivant. Both sexes found him charming. Despite his wit, Degas was a bundle of nerves. A petulant introvert, it’s likely Degas remained celibate throughout his life.

At the time of their meeting, both Manet and Degas were in the process of renouncing their training in academic art and had turned their backs to the religious or allegorical subjects that were de riguer in mid-19th century painting. Manet and Degas adhered to the credo of the influential poet and essayist Charles Baudelaire, whose rallying cry was for artists to “be of their time.”

Manet emerged in the 1860s with paintings that blended the historical and the contemporary, as seen in his 1863 cause celebre Olympia, which had its basis in a Renaissance work. But it was the brazen look on Manet’s subjects that set them apart. Degas left behind the academic teachings of the neoclassicist Ingres, and was a quick convert to the painting of modern life. By 1866, he was entrenched as one of the young avant-gardists. Degas’ Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey included in today’s exhibition, signaled his commitment to contemporary subject matter. Together the duo influenced the Impressionists.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. Musée d’Orsay

Edgar Degas, Scene from the Steeplechase, The Fallen Jockey, 1866, private collection. Wikimedia commons

Manet never joined the Impressionists although many see him as their godfather. He remained very close to the Impressionists and their salons. It was hard to define Degas. The diversity and richness of his subjects and working techniques set him apart. Degas exhibited with the Impressionists, although he pushed the definition to its limits.

Now on with the show…

What put Degas apart from other Impressionists was his disinterest in the plein-air study of nature, light, and shadow. He said to his compatriots, “you need the natural life, I need the artificial.” Instead, he turned to the grittier, urban life of people absorbed in their occupations. These included café singers, prostitutes, but also hard-toiling laundresses and milliners.

The yawning woman in Degas’ Laundresses (1884-86) is included in the exhibit and she’s a candid example of women at work. His Women on the Café Terrace in the Evening (1877) explores the ennui of another group of working women, prostitutes — bored, and between assignations. Degas’ smudgy pastel adds to the haze of a nighttime vignette. At 41x 60 cm, it’s much smaller than I would have imagined.

Degas, The Laundresses, Musée d’Orsay. Wikimedia Commons

Degas’ method of painting indoors set him aside from the Impressionists. Degas would have no interest in setting out to paint a more natural subject like Manet’s Boating (1874), where you can feel the sun on the painter’s back.

Edouard Manet, Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Of course, Degas did venture outside. Manet often painted indoors, but then again, he’s not regarded as an Impressionist. An en plein air example of Degas’ is Beach Scene (circa 1869), which shows a motherly woman intently combing a child’s hair while sprawled on a sandy beach. Subsequently, a model hired by Degas reported that, “He’s a strange gentleman – he spends the whole four hours of the sitting combing my hair.” Degas’ strange attitudes toward women greatly influenced his painting.

Edgar Degas, Beach Scene, The National Gallery of Art London

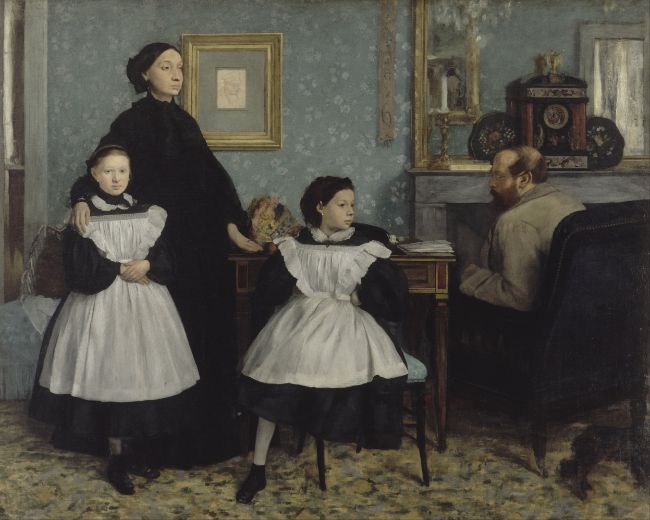

Degas’s women don’t exist as individuals as they do in Manet’s work. I think the only two females in the exhibition that firmly look at Degas are the child in the Belleli Family grouping and Degas’ sister Thérèse found in Edmond and Thérèse Morbilli (1865). A bachelor, Degas remained on the outside looking in, giving him the reputation as a voyeur. His candid, yet blunt, peeking-through-the-keyhole perspective included women bathing privately in shallow tubs or drying themselves in uncomfortable poses. The Tub (1886) is an example of this keyhole voyeurism where he seems to be encroaching on the bathers’ private space, despite her intricately arranged pose. For the sake of comparison, the curators have included 1878’s Woman in a Tub by Manet, but it’s not well known. Degas’ Interior: AKA, the Rape (1868) places the viewer in the room of a woman at her most debased.

Edgar Degas, The Bellelli Family, Wikimedia commons

Edgar Degas, Edmondo and Thérèse Morbilli, about 1865, Museum of Fine Art Boston. Wikimedia Commons

Edgar Degas, The Tub, 1886, Musée d’Orsay

Edgar Degas, Intérieur, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons

Manet liked to be seen. His bemused models always met his gaze, a complete contrast to Degas’ women. Manet grew attached to his models and generally, they found him charming. Two of his favorites are included in Manet/Degas.

First came Victorine Meurent, his model for Olympia, his submission for the Paris Salon of 1865. Olympia is a highlight of any trip to the Orsay and she’s here, nicely situated, so you can catch a glimpse of her as you move from room to room. She’s nude – that was nothing new, but her importance to the history of art is her unflinching look, which threw most of its viewers off kilter. Emile Zola defended Manet, saying his friend was a painter, not a moralist. When admiring Olympia/Victorine, keep in mind that 160 years ago, visitors compared her to a gorilla, or a green and decaying corpse. How times have changed.

Then, there is Manet’s famous muse Berthe Morisot, the talented Impressionist who would become his sister-in-law. The musée includes a bank of paintings dedicated to her: Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, (1872) the Repose (1870) and Berthe Morisot Reclining, a small, quietly seductive painting (1873). Berthe had a toquade, or crush, on the painter; and when she looks you in the eye, remember that she loved Manet.

Edouard Manet, Berthe Morisot and Violets. Photo by Hazel Smith

Manet was a full-time flirt and seemed to have little time for his wife and a child, whom he never owned up to. He was married to Dutch pianist Suzanne Leenhoff, hired by Manet’s father to be his grown son’s piano teacher. What an interesting subterfuge!

Edouard Manet, La Repose, Rhode Island School of Design

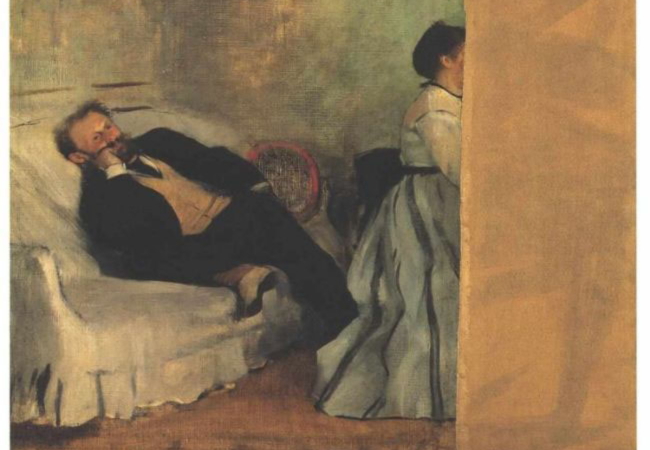

Degas and Manet began trading paintings with each other. Manet had given a still life of plums to Degas. Degas gave Manet a much more personal work, a double portrait of Manet and his wife, with Manet lolling on the sofa as the upright Suzanne, played the piano: Édouard Manet and his Wife (1865). Degas’ gesture paid homage to their relationship. However, when Degas next visited chez Manet, he found that the right quarter of his painting had been cleanly sliced off and Suzanne’s profile removed. In Ambrose Vollard’s Recollections of a Picture Dealer, Degas tells the collector, “Manet thought his wife didn’t fit into the picture.” A huge fuss was made. In my opinion, the slashing may not have been a judgement of Degas’ talent, but a couple’s squabble – Manet was in the midst of developing a tender model/artist dialogue with Morisot. However, Degas’ response was “Monsieur, I am sending back your ‘Plums.’ “

Oh, if these walls could talk! The two patched things up. Degas noted to Vollard, “How could you expect anyone to stay on bad terms with Manet?” Nevertheless, the painting remained unpatched for a long time.

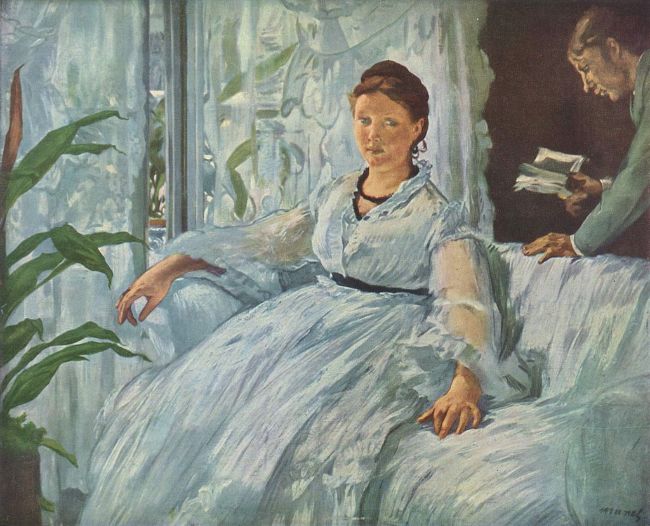

Manet, in response, created a replacement portrait of Suzanne in exactly the same pose, but no prettier, Madame Manet at the Piano (1868). This, and another Manet rendition of his wife, are included in the exhibition. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder but a much prettier Suzanne is portrayed in Manet’s The Lecture. His delicate use of white lifts her rather solid form to the realm of the angelic.

Édouard Manet, Madame Manet au Piano

Edouard Manet, la Lecture

Not to be confused with Degas’ gift of plums is Manet’s The Plum, painted circa 1877. It hangs next to Degas’s Absinthe Drinker (1875-6). The actress Ellen Andrée is the model for both, but hardly recognizable as the same woman. It’s an excellent comparison.

Edouard Manet, The Plum, National Gallery of Art

Edgar Degas, The Absinthe Drinker. Photo by Hazel Smith

Both paintings depict women who have had a long and drunken evening at the Nouvelle Athènes, a bar the duo frequented. A world-weary Andrée inhabits Manet’s version. Degas’ work shows Andrée in clown-like lugubriousness sitting next to another equally comic figure. Even her clumsy feet dangle like a child. The awkward flat planes of the tables pen Degas’ subjects away from the viewer. What’s the reason for this? The medium of photography deeply interested Degas. Historically, many of Degas’ paintings are oddly framed, or cropped like snapshots, and many instances of Degas’ technique are included in the show, one example of his deliberately odd framing is The Tub mentioned above.

Manet’s The Balcony (1868) is another gem in the Orsay’s permanent collection featuring Berthe Morisot. Her image and her reputation are metaphorically barricaded from the street by the verdigris balcony. It was the first time Manet painted her and she was risking her good reputation by being portrayed by a man with an infamous one.

Edouard Manet, The Balcony, Musée d’Orsay. Photo by Hazel Smith

There are hats galore on the canvases of these two men. Milliners had an infamous reputation. These hard-working women were known for turning tricks to make ends meet. Given Degas’ prurient reputation, I’m sure he knew that full well when he repeatedly painted them. Here is his Millinery Shop, finished in 1866. Manet’s The Milliner (1881) is included in the show, but it’s so uncharacteristic of his style it defies comparison.

Edgar Degas, The Millinery Shop. Wikimedia commons

Both artist were excellent portraitists. Included in the exhibition are paintings of the Degas family including his almost identical younger sister. Manet includes his folks too but one of his prized pieces in the show is his intricately detailed portrait of Emile Zola (1868). Look for Olympia tacked up on the writers’ “inspiration board.” Manet knew how to use the infamous back that would soon disappear from the palette of the Impressionists. The use of black is a real no-no in painting but Manet pulled it off in his Portrait of Emile Zola. The gallery has decided to contrast it with Degas’ seated portrait of the artist James Tissot, one of my favorites of that time.

Edouard Manet, Emile Zola, 1868, © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay)

Adding to the rogues’ gallery is a precious album with photos of Manet, his student, Eva Gonzales, and what is assumed to be one of Manet’s favorite models – Victorine Meurent. This album is deeply interesting and I have pored over it on the BNF website.

Jointly, Manet and Degas had a profound affect on the course of modern art. Manet died at just 51. Degas bought dozens of his friend’s paintings until his own death in 1917, 31 of which are displayed in the exhibition. The Manet/Degas show is a highlight of Paris’ art calendar. It’s a must-see.

DETAILS

The Manet-Degas exhibition runs until July 23, 2023. The full-price ticket is 16 euros.

Musée d’Orsay

1 Rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 7th arrondissement

Closed Mondays

Lead photo credit : Édouard Manet and Mme. Manet, 1868–1869, Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art, Japan Wikimedia commons

More in Art, Degas, Manet, Musée d’Orsay, painting

REPLY