The Paris of Artist Francis Bacon

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Francis Bacon called Paris “my other city.” When he tired of his excesses in London, the British artist returned to Paris like a homing pigeon. He needed the culture, art, intellectual possibilities – not to mention French food and wine – and his old friends.

He discovered Paris as a young man in the 1920s, living with little money in rundown hotels. He survived by picking up men in bars like Le Select in Montparnasse. He spoke almost no French when, at an exhibition, struggling to understand the guide, he was befriended by Yvonne Bocquentin, an amateur musician and lover of the arts. Bocquentin was so taken by the cherubic visaged Bacon that she took him home with her to her elegant house in Sainte-Maxime near Chantilly. And it was here in this bourgeois household alongside Jacqueline’s husband Pierre and small daughter Anne-Marie, that Bacon learned not only French culture, literature and cuisine, but also art in its many forms.

Le Select, 99 boulevard du Montparnasse. Credit: Celette/ Wikimedia Commons

(Bacon fit in perfectly with this bourgeois family. His parents were part of the wealthy Anglo-Irish society who held estates around Dublin — they were deeply resented by the Irish. Bacon lived through these times of mounting IRA aggressions in a family where he too felt alienated. A sickly child, he had a total disinterest in hunting and riding and a father who brutalized him. His growing contempt for religion added to his loneliness and isolation. Only his beloved Nanny Lightfoot gave him the love he craved. He would support her until the day she died.)

The nine months spent with the Bocquentins afforded Bacon an immersion into French living that would influence his love of France for the rest of his life.

As a young man, Bacon was eager to be surrounded by the exciting artistic life of Left Bank Paris, never so vibrant and innovative as during the Roaring Twenties. From the bohemian Hotel Delambre in Montparnasse, where Bacon rented a cheap room, he walked the same streets as Paul Gauguin, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Man Ray, Henry Miller and his idol Pablo Picasso, whose work later made a profound effect on him. But at that time, Bacon had no realistic thoughts of becoming a painter — being surrounded by talented artists was daunting enough to dispel any latent ambition.

Instead, his interests were leaning towards decorating and design, and Paris was ahead of the curve. Art Deco had opened the doors for new contemporary furniture. Bacon studied and designed furniture and rugs under respected designers such as da Silva Bruhns and Eileen Gray, but he did not believe that he could make a living in Paris and, at 18 years old, decided to return to London to try his luck there.

Eileen Gray circa 1910. Wikimedia Commons

Despite a modest success with his own interior design studio in Queensbury Mews – after all, Bacon was a talented, beguiling young man who still had contacts in Paris and Berlin, and the items he designed proved popular – he was once more in the milieu of painters. His growing desire to be an artist became harder to dismiss.

By 1931, Bacon had given up interior design and with the help of friends, odd jobs and rich lovers, he dedicated himself to painting. Critics were fiercely divided on both his subject matter and even his talent. The 1944 triptych “Three studies for figures at the Base of a Crucifiction” provoked outrage in the London art world. Two years later, “Painting” depicted the crucifixion in a slaughterhouse. The religious theme that obsessed Bacon resulted in the “Screaming Pope” series of paintings. He was influenced by Velasquez, particularly by the 1640 painting of Pope Innocent X.

Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953, Francis Bacon. Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa

In November 1946, the war just over, Bacon returned to a much gloomier Paris. Food rationing was still in effect and the buildings were soot covered and often in disrepair. This time Bacon chose the Right Bank and checked into the Hotel Saint-Roch near the Tuileries and the Louvre. As always, the hotel was inexpensive but critically within easy walking distance to numerous art galleries. Despite eschewing his usual haunts in Montparnasse and Saint-Germain, Bacon was introduced to Isabel Rawsthorne, an English artist who modeled for Giacometti and knew Sartre and Picasso. (She was probably the lover of Jacob Epstein, who designed Oscar Wilde’s tomb.) They became life-long friends, and Bacon eventually painted her.

The tomb of Oscar Wilde with the protective glass barrier. Photo credit: Agateller, Public Domain

Lack of money was always a problem for Bacon and he drifted between Monaco, Tangiers and London. His exploits in Soho were already legendary and his masochist preferences often verged on the dangerous. (Friends had even warned about his lover, Peter Lacey, saying he was so violent, he’d eventually kill Bacon.) His paintings thus reflected the tormented violence, the brutality of life stripped bare. Since homosexuality was still illegal in England, his 1953 painting “Two Figures” could not be exhibited. Instead it was bought by Lucien Freud.

Gradually Bacon was making a name for himself both in London and in Paris where, in 1956, he had a one-man show exhibiting 20 paintings at the Galerie Rive Droite. But Bacon was famously generous and profligate with money. By 1957, he was broke once more. He returned to a Tangiers inhabited by the likes of William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) by Francis Bacon

Back in London, Bacon was signed by the Marlborough Gallery and in 1962, Bacon’s exhibition at the Tate Gallery was viewed by over 100,000 people. The following year, Bacon met perhaps his most infamous lover and model: George Dyer— an occasional crook, cat burglar, and a friend of the notorious Kray twins. Ill educated but well dressed, and with his broken boxer’s nose, Dyer was the epitome of a loveable cockney rogue. The prodigious disparities in their backgrounds and educations, plus Dyer’s heavily muscled body, were irresistible to Bacon and he never tired of painting him.

Bacon had always been a heavy drinker and now with money, Bacon’s wild nights in Muriel Belcher’s Colony Club on Dean Street and Wheelers in Soho became the stuff of legend. (Bacon introduced Miro and Giacometti to the unbridled hedonism of 1960s Soho. Whether either fully recovered is not noted.)

Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror, Francis Bacon, 1968. Oil on canvas. 198 x 147 cm. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Even though the 1960s was cementing Bacon’s reputation in England, it was also an era where new, young artists were also making a name for themselves. In his 50s, Bacon could no longer be considered their contemporary.

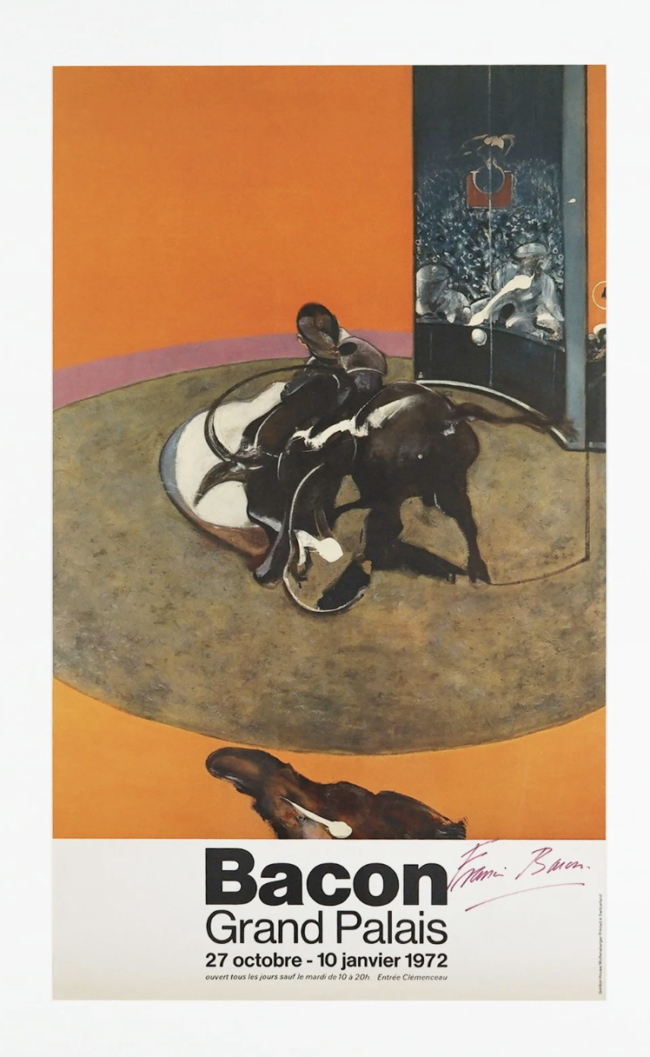

In 1969, the French curator Blaise Gautier visited Bacon in London and asked him if he would be interested in a retrospective in Paris. Bacon set his sights on the Grand Palais, and the French government agreed. The magnificent, glass-roofed landmark on the Champs-Élysées was Bacon’s for the autumn of 1971. Bacon selected 134 paintings including 10 monumental triptychs. Bacon took Dyer with him to Paris and booked into the Hôtel des Saints Pères in Saint-Germain.

Grand Palais poster, 1971, signed by Francis Bacon. Image: hiddengallery.co.uk

The retrospective “Francis Bacon: 26 October 1971 – 5 January 1972” was opened by French president Georges Pompidou. It was an astounding success and one of Bacon’s proudest achievements.

The left panel of one of the triptychs, “Three figures in a Room,” depicted George Dyer slumped over a toilet. Dyer had been found dead in this same position in the hotel the previous day. His death was not announced until the day after the exhibition. News of Dyer’s macabre death would have overshadowed Bacon’s triumphant opening and the hotel manager was persuaded to lock the room where Dyer was still slumped on the toilet and announce the news the following day.

Dyer’s untimely death did not discourage Bacon. Instead he returned to Paris more often, not only staying in the same hotel but requesting the room in which Dyer had committed suicide. Dyer’s death had a profound effect on Bacon; he was lonely and continued painting him. Soho was no longer the same, friends were dying and he was tiring of his life in London. In 1974, Bacon bought a studio on Rue de Braque in Le Marais.

Rue de Braque in the Marais district. Photo credit: Ralf.treinen/ Wikimedia commons

Bacon was once more beguiled by Paris. Sonia Orwell (George Orwell’s widow) introduced Bacon to Le Tout Paris, and he enjoyed literary conversations at dinner parties. He still enjoyed his nighttime activities, but they were becoming less frenzied, the settings more sophisticated. He liked the chic bars on the Rue Sainte-Anne in the second arrondissement and the club Le Sept, a gay club whose entrance requirements were simple — you had to be beautiful. Frequented by the likes of Mick Jagger, Rudolf Nureyev and Karl Lagerfeld, Le Sept was a place where art and fashion mixed. Bacon still loved the Left Bank and his favorite bar was La Palette, where he could dine undisturbed in the back room. To this day, La Palette is a small and unpretentious bar/restaurant on Rue de Seine.

La Palette. Photo credit: Pedro J Pacheco/ Wikimedia Commons

Although his studio was perfect for painting, Bacon’s love of Paris often lured him outside to walk the streets and simply admire the architecture. Then in 1977, the Galerie Claude Bernard in the rue des Beaux Arts showed 20 pieces. Despite the police closing off the street to traffic, more than 5,000 people channeled through the narrow street in a frenzied matter of hours. It was another overwhelming triumph for Bacon.

Francis Bacon died in Madrid in 1992 at the age of 82. He had destroyed many of his paintings during his lifetime but his last unfinished painting, still on the easel in his London studio, was a meditation of his death.

In 1996 and again in 2019/2020, the Centre Pompidou held a major retrospective of Bacon’s paintings spanning 1971 to his death. Last year, Barry Joule— Bacon’s close friend and neighbor — announced that he was donating a large collection of Bacon’s works to the national archives of the Centre Pompidou.

The triptych of George Dyer had helped make Bacon the most expensive artist in the world. But it was Paris that had been a catalyst in Bacon’s success — his beloved “second city” heralding and celebrating his stratospheric rise in the art world.

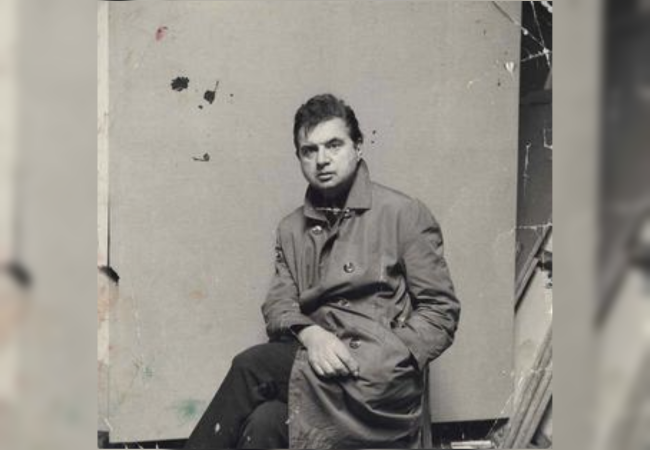

Lead photo credit : Bacon photographed in the early 1950s. Credit: John Deakin / Wikimedia Commons

More in Francis Bacon