Paris Cemeteries & their Secrets: Oscar Wilde’s Tomb at Père-Lachaise

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Père-Lachaise— perhaps the most famous and beloved cemeteries in Paris– was not so beloved when it first opened in 1804. As the graveyards in Paris filled to overflowing, new cemeteries were built outside what were the city precincts: Montparnasse in the south, Montmartre in the north, and Père-Lachaise in the east.

Père-Lachaise was considered too far from the city to be a desirable place to be buried and fewer than 14 graves graced the cemetery after its opening. The cemeteries’ administrators approached the problem with the brilliant strategy of transferring the remains of Jean de la Fontaine and Molière, with great fanfare, to Père-Lachaise. In 1817, the purported remains of Abelard and Héloïse were also transferred there. And so began the popularity of Père-Lachaise. The desire to be buried amongst famous people resulted in the growth and expansion of the cemetery, and today, more than a million people are buried in the park-like grounds. And the columbarium holds the cremated remains of an estimated two million more.

Père-Lachaise has become a tourist ‘must see’ site in Paris– not only for the chance to see famous graves: Marcel Proust, Henri Salvador, Chopin, Delacroix, Bizet, Jim Morrison, (the list is endless); but also for the beauty and tranquillity of this urban oasis of calm. It is utterly fascinating: old telephone box-like tombs are interspersed with more recent, odd, eccentric and frankly mad, gravestones. All this with a background of birdsong and fabulous views across the city.

However one on my own favorites and probably the easiest to find (Jim Morrison’s took me two visits and a lot of undignified scrambling)– is the tomb of Oscar Wilde, the Irish author, playwright and poet.

When Oscar Wilde died on November 30, 1900 in room 16 of the then seedy Hotel d’Alsace in Rue des Beaux Arts St Germain, Robbie Ross, his devoted friend and first homosexual lover, was by his side.

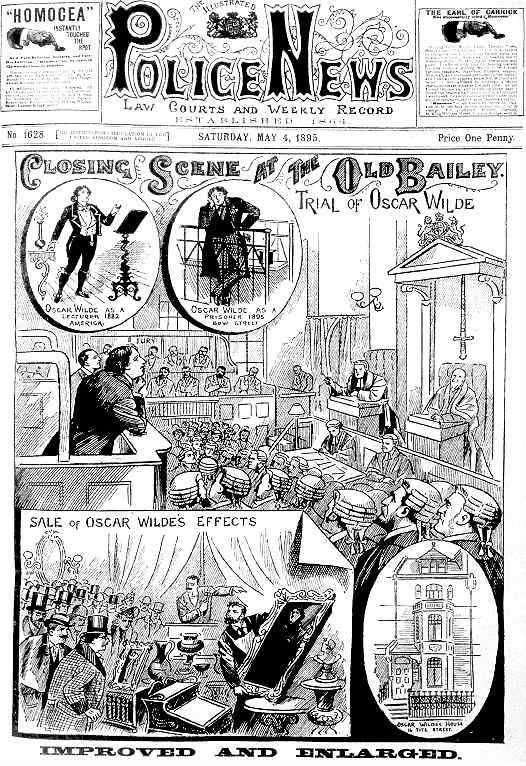

Wilde died of cerebral meningitis after an operation for an ear infection. After he had served his two-year prison sentence for sodomy and gross indecency, the harsh conditions, particularly in Pentonville and Wansdworth before he was transferred to Reading Gaol, had broken his health. He was disgraced and bankrupt and left England for Europe immediately on his release from prison, never to return. Robbie Ross had begged him to leave England before the court passed sentence, rightly fearing the outcome, but Wilde had refused. Once the most celebrated and feted man in England, Wilde was now despised, an outcast, his career in ruins.

The Hotel d’Alsace was the end of the line for Oscar. (Now simply called L’Hotel, it is an exclusive five-star hotel where Wilde’s old room can be rented for upwards of 300 euros a night. The wallpaper, of which Wilde famously said, “Either this wallpaper goes or I do”, has fortunately being replaced.)

After Wilde’s release from Reading Gaol, a reconciliation with Bosie (Lord Alfred Douglas) had ultimately been unsuccessful. Wilde was deserted by most of his friends, and it was the faithful Ross who had never wavered in his support and love; Ross was with him until the end.

Ross was the grandson of the Canadian reform leader Robert Baldwin. He was openly and defiantly homosexual in a period when homosexuality was not only illegal but socially, scandalously unacceptable. Ross seduced Wilde when Wilde’s wife was pregnant with their second child.

Ross was then 17 years old.

Robbie Ross was a journalist, art critic and dealer. Later, as Wilde’s literary executor, he worked tirelessly to retrieve the copyright of Wilde’s work which had been lost on Wilde’s bankruptcy. However, even Ross could not prevent the initial ignominy of Wilde’s demise.

Oscar Wilde had a pauper’s burial in Bagneux cemetery on the outskirts of Paris.

It was nine years later that Ross– with the help of donations from Wilde’s admirers– had the author’s remains transferred to Père-Lachaise cemetery in July 1909. An anonymous donation of £2,000 (later to be revealed to be from Helen Carew), allowed Ross to commission the monument for Wilde’s grave. This vast, sphinx-like winged figure was to cause immediate and lasting controversy from the moment it left Jacob Epstein’s studio in Cheyne Walk, London and arrived in Paris.

The monument was carved from a 20-ton block of stone. French customs immediately levied a £120 tax on it, but worse was to follow. The reaction of Parisian officials to the monument’s nakedness was a decree that the monument be covered by a tarpaulin in daylight.

The objection was to the size of the winged figure’s testicles. They were considered disproportionately large and therefore offensive.

Returning to the cemetery one evening to work on the monument, Epstein was enraged to discover that the testicles had been covered with plaster. By then the monument was being kept under police surveillance and only by bribing a police officer could Epstein sporadically continue to work on the monument at night.

Robbie Ross, attempting a compromise, instructed that a bronze plaque in the shape of a butterfly should be placed over the offending body parts. When the monument was finally unveiled in August 1914 by Aleister Crowley, Epstein, furious that his work had been altered, refused to attend the unveiling. A few weeks later, Crowley caught up with Epstein in a bar. Crowley was wearing the bronze butterfly around his neck and informed Epstein that his work was now as he had intended.

The monument’s testicles continued to offend and in an act of wilful vandalism, were completely removed in 1961. The rumor was that the cemetery manager used them as paperweights.

The testicles were never recovered.

In 2000, Leon Johnson, a multimedia artist, installed a silver prosthesis to replace them.

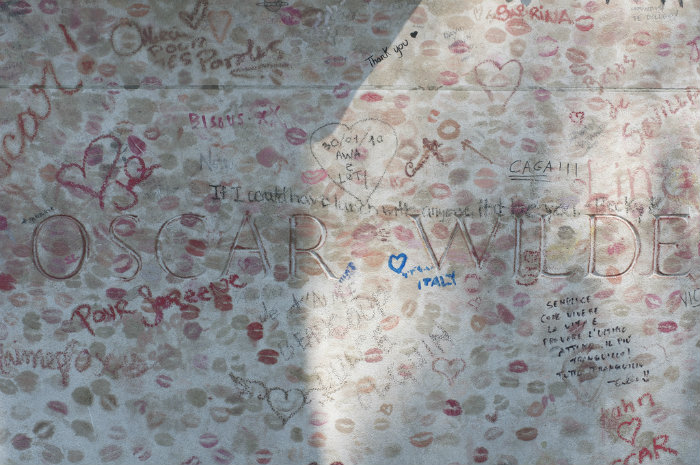

Controversy over Wilde’s monument continued unabated when a tradition developed whereby fans would kiss Oscar’s tomb deliberately leaving colorful lipstick marks.

In 2011, a glass barrier was finally erected around the monument to “protect it from vandalism,” making it kiss-proof.

On commissioning the monument, Robbie Ross had requested that a small compartment be left for his own ashes.

In 1950, on the 50th anniversary of Wilde’s death, Robbie Ross finally joined his lover and greatest friend when his ashes were placed in Wilde’s tomb in Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Oscar Wilde’s tomb can be found on Avenue Carette inside the idyllic cemetery.

Photo credits: Looking down the hill at Père Lachaise by Näkymä Père-Lachaiseen/ Public Domain; Oscar Wilde by Napoleon Sarony/ Public Domain; Oscar Wilde Trial from The Illustrated Police News, 4 May 1895/ Public Domain; The tomb of Oscar Wilde with the protective glass barrier by Agateller, Public Domain; Tomb of Oscar Wilde by Aleksandr Zykov/Flickr

Lead photo credit : Looking down the hill at Père Lachaise. Photo: Näkymä Père-Lachaiseen/ Public Domain

More in Paris cemeteries

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY