The Beautiful Spy: The Unsung Heroine of World War II

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On a hot and humid July evening in 1944, Gestapo officers knocked on the door of Germaine Pezet, a Parisian housewife then living in Aix-en-Provence. They were on a mission to find whatever information they could about the Resistance organization known as “Alliance” and its leader, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade. After turning the apartment inside out, they left empty-handed. Germaine Pezet breathed a sigh of relief. With dyed hair, thick eyeglasses, and a dental prosthetic, no one, not even those Gestapo officers, believed she was the very person they were looking for.

“How did a beautiful, young woman who had dreams of becoming a concert pianist become the leader of the largest Resistance organization in France and the greatest spy in Europe?” This question is answered by Lynne Olson in her compelling historical novel, Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler.

Marie-Madeleine was born into a wealthy family on November 8, 1909 in Marseille, France. She spent her childhood in Shanghai with her family: her father, Lucien Bridou, an executive with the French Maritime service, her unconventional mother, Mathilde, and her two siblings, Yvonne and Jacques. Shanghai was a thriving trading port and colonial quarter during the 20s, known as the “Paris of the East.” It was filled with Chinese warlords, White Russians and myriad other characters who made a lasting impression upon her. In his autobiography, British novelist J.G. Ballard, who was born and raised in Shanghai during this era, recalled ”… Anything was possible, and everything could be bought and sold.” Within this exotic and mysterious environment, Marie-Madeline was educated at the convent school, Couvent des Oiseaux and the music school, Ecole Normale de Musique. This idiosyncratic background coupled with her eclectic education helped to make her the extraordinary woman she became.

At the age of 18 Marie-Madeleine left her husband, Édouard Méric, a French army officer serving in Morocco, and moved to Paris with their two children. Méric wanted her to be a traditional wife, but she was anything but traditional. Having grown up in the wild and exotic world of Shanghai, her innate sense of adventure and independence doomed the marriage from the start and they separated. Still in her mid-20s, she began to create a life for herself: she learned how to fly a plane, drive a car, and obtained a job, despite the restrictive patriarchal attitudes in France at the time. In fact, French women weren’t granted the right to vote until 1944 by Charles de Gaulle’s government in exile.

German soldiers parade on the Champs Élysées on 14 June 1940. Credit: Creative Commons/ Wikipedia

One spring afternoon while attending a crowded gathering at her sister Yvonne’s house, filled with diplomats, journalists, business leaders and military men, Marie-Madeline met the young Lieutenant-Colonel Charles de Gaulle and political rival, intelligence officer Major Georges Loustaunau-Lacau. She became occupied with the question of the war effort, which the two men were arguing about vociferously. Hitler had just crossed into the Rhineland, a previously off-limits buffer zone created as part of the Treaty of Versailles which ended World War I, and neither France nor England were doing anything about it. Having had no direct experience of the brutal impact World War II had on the French people, it was unthinkable to her that no one was resisting the Germans.

Marie-Madeleine Fourcade. Photo used on a fake identity card when she fought for the Resistance. Public domain

Impressed by her keen intelligence and courage to speak her mind, Loucaustau-Lacau recruited Marie-Madeleine to work for his underground magazine, L’Ordre National, covering military action in Europe, and as a spy-in-training. Joining the Resistance formally in 1940 as one of an elite handful of men and women who rose up in defiance of the Nazis, her sheer determination and impressive organizational skills propelled her into the job of creating networks of agents throughout unoccupied France. She named each agent after an animal or a bird (later dubbed Noah’s Ark by the Germans) for security purposes. Marie-Madeleine chose the name, Hérisson, hedgehog, for herself.

Image credit: Unsplash, lesanderson

Olson’s driving narrative follows a circuitous path through the Cote d’Azur, the Dordogne, Brittany and Burgundy as Marie-Madeleine recruits spies, radio operators, pilots and couriers comprised of former military men, doctors, lawyers, artists, housewives, fishermen, students, and even a child actor. By 1941, this group, known as “Alliance” became the largest and most important Allied intelligence force in France.

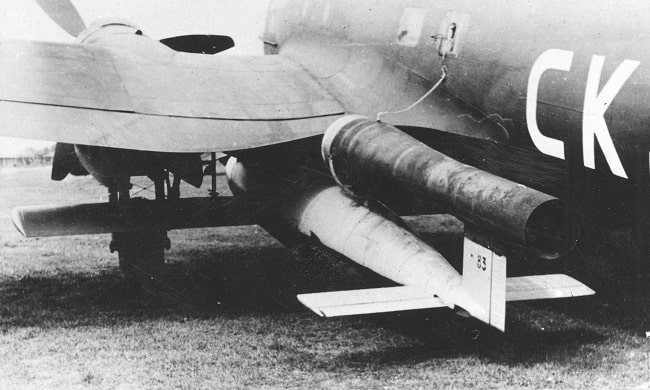

In 1941 when Loucaustau-Laucau was arrested and sentenced to two years in prison, Marie-Madeline became the head of Alliance. Her charisma and total immersion in her role convinced even the most doubtful men. Gabriel Rivière, the head of the underground’s Marseille operation, exclaimed, upon meeting her for the first time, “Good God, a woman!” She proved more ingenious and fearless than even some of the men she recruited. Throughout the war, the 3,000 strong Alliance network supplied the British Secret Service, and American high command unparalleled access to Hitler’s plans, including the V-I flying bomb and V-2 rocket program, German troop movements, and an exact, 55-foot-long roll-up map of the beaches and roads onto which the Allies would land on D-Day.

Image credit: Flickr, (CC BY 2.0)

By the end of 1942 Marie-Madeleine was on the run from the Gestapo. No one, not even the Nazis, imagined the head of the largest spy network in France was a woman. In constant mortal danger, she escaped capture by sheer will, once hiding in a mailbag on a nine-hour, freezing train ride to Spain. French Navy Capt. Jean Boutron, who smuggled her out of France said, “She was terribly feminine, but she has more willpower than most men.” Another time she escaped by squeezing her emaciated naked body through the window bars of her prison cell. “She just didn’t give up.”

Marie-Madeleine’s delicate emotional state and grave physical condition by 1943 were a cause of concern to the head of British Secret Service, Sir Hugh Sinclair. He had her evacuated to London where she regained her stamina during the course of a year. Upon learning that many of her agents had been arrested, sent to concentration camps or murdered by the Germans, she returned to France in August 1944. Landing in Provence on the eve of the Allied invasion there, she quickly set about to restore her decimated network. Despite her efforts, by the end of the war more than 400 agents had given their lives for their country.

A German Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 H-22. This version could carry FZG 76 (V1) flying bombs, but only a few aircraft were produced in 1944. Some were used by bomb wing KG 3. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

Marie-Madeleine’s personal life was complicated. During the war she fell in love with French Air Force pilot Léon Faye, who joined her network as her deputy, and had his child. Her children by Méric and Faye were sent to Switzerland for their protection, yet she always felt guilty for choosing her country over them. When the war was over, she finally divorced her first husband, Édouard Méric, and married industrialist Hubert Fourcade. They had two children together.

After the war Marie-Madeleine provided assistance to former members of her network. She was VP of the International Union of Resistance and Deportation and of the National Association of Medalists of the Resistance since 1947. In 1968 she published a memoir of her war years aptly titled, Noah’s Ark. She was also a member of the European Parliament between 1980 and 1981.

Père Lachaise Cemetery. Image credit: Flickr, Oh Paris

Marie-Madeleine Fourcade died on July 20, 1989 and was the first woman to have her funeral services performed at Les Invalides, the historic site of the tomb of Napoléon Bonaparte. She is buried at Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The inability of modern historians to acknowledge her inestimable importance speaks volumes to the second place role women have played in world affairs. Marie-Madeleine refused to accept the abolition and dishonoring of humanitarian values, something we all need to be reminded of. Conspicuously, Charles de Gaulle did not include her among the designated 1,038 Resistance heroes and heroines (of which there were only six women) due to his political rivalry with her champion, Georges Loustaunau. Without the dedicated research and impassioned retelling of Marie-Madeleine’s story by Lynne Olson, we wouldn’t know about this remarkable woman.

Below find a link to purchase Lynne Olson’s novel, Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler.

Love Paris as much as we do? Get some more Paris inspiration by following our Instagram page.

Lead photo credit : Women's suffrage demonstration in Paris on 5 July 1914. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

More in Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, Resistance, Second World War, World War II, World War II in Paris, WWII

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY