The Smart Side of Paris: Across the Street from the Louvre

It is impossible to count the millions of people who have passed by the Oratory of the Louvre (l’Oratoire du Louvre) without noticing it. Directly across the street from the Louvre Museum, running from 145 Rue Saint-Honoré to 160 Rue de Rivoli, the beautiful Protestant church, with one of the finest pipe organs of any church in Paris and an imposing statue of the now forgotten Gaspard de Coligny outside, is today the center of a thriving Protestant congregation. A sadly neglected tourist site, the informational sign in front hints at a time of religious tension now past, a time in which scholars were inventing the field of biblical scholarship. The sign reads (in French): “Gaspard de Coligny had made the choice to become Protestant. The Reform message continues to invigorate the members of the [congregation of] the Oratory of the Louvre. The Church offers a meeting place for reflection, for meditation. The Oratory is a place where the gospel lives in dialogue and is embodied in mutual aid: a Church to think and believe in complete liberty.”

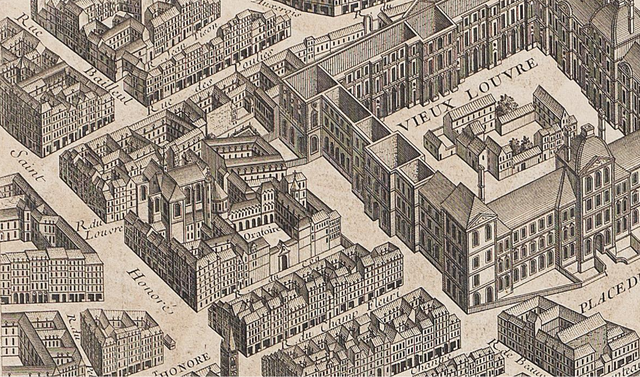

Fragment of Turgot’s map, 1739, with the Louvre Oratory. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The church’s history is interesting enough to merit its own book. (Those who read French can find it in Philippe Braunstein’s 2011 history of l’Oratoire). It owes its existence to an unusual and paradoxical individual, Pierre de Bérulle. Bérulle was a Catholic priest, Henri IV’s chaplain, a powerful statesman, something of a mystic (although opposed to certain kinds of mysticism), author of at least six books, an ardent advocate of reforming the French clergy, a vehement opponent of French Protestants (who were known as Huguenots), and a man who apparently “did not know how to smile.” In 1611, Bérulle founded the Society of the Oratory of Jesus, “the army of the Catholic Counter Reformation,” whose members would be known as Oratorians, and built a chapel on the current site of the Oratory of the Louvre. The chapel and the new order attracted numerous adherents and visitors, and soon had to be expanded. In 1623, the Oratory became the official Royal Chapel. In fact, Louis XIII’s and Cardinal Richelieu’s funerals were both held there. The Revolution shuttered it and in 1811 Napoleon gave it to Protestants, in whose hands it remains to this day.

Bust of Pierre de Bérulle by Michel Anguier (1612–1686). Formerly in his tomb at the Oratoire du Louvre, now on display at the nearby Saint-Eustache Church. Credit: Chabe01 / Wikimedia Commons

The irony of a Catholic king’s chapel being turned into a Protestant temple is delicious; but my story pertains more to the phrase from the sign in front of the church: “a place where the gospel lives in dialogue.”

It was in this building that one of France’s greatest (and most forgotten) intellects catalogued Eastern manuscripts and devoted a great deal of time to biblical and linguistic studies. His name is Richard Simon and, surprisingly, in a city of 6,100 streets in which seemingly every great writer gets a street name or a plaza, Richard Simon is neglected. Exactly why Simon is largely forgotten is difficult to say. True, his writings were highly controversial — but that is the type of peccadillo that the French relish. He was expelled from the Oratorian order, but that is something of a badge of honor among freethinkers. The great French thinkers of the 18th century —Denis Diderot, Voltaire, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, Jean-Jacques Rousseau — ignored him. Despite his ideas being deeply woven into the fabric of thought in the 18th century, it is probably because the philosophes ignored him that he is nearly forgotten today.

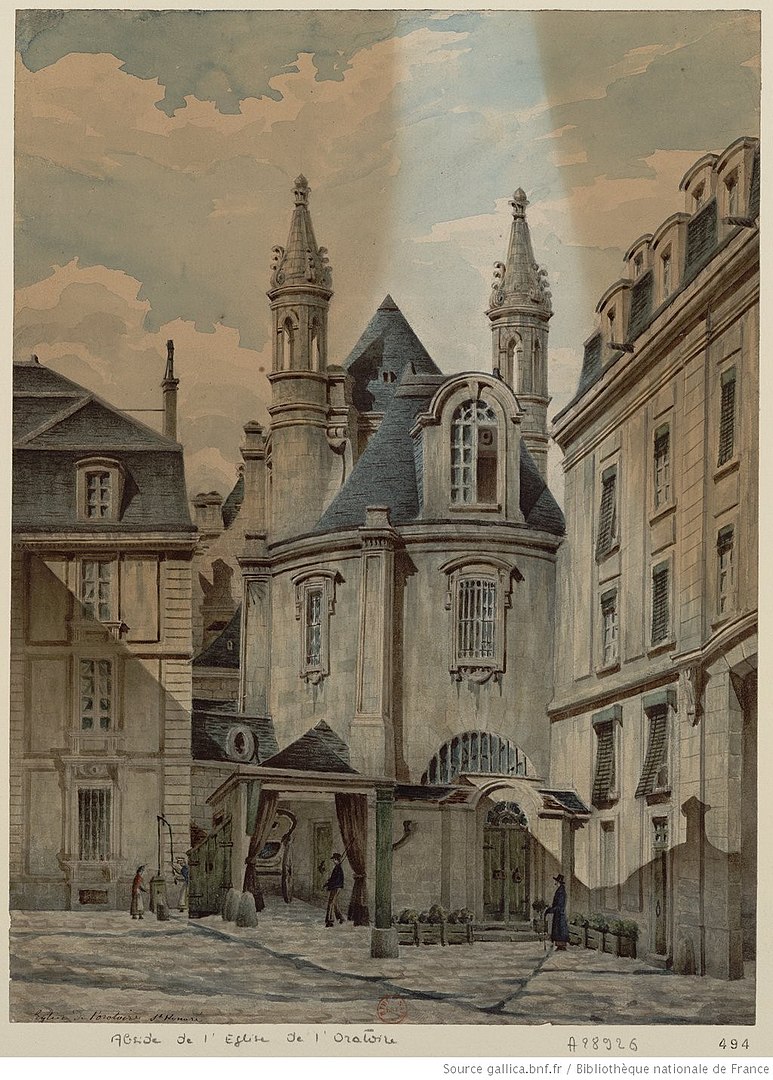

The apse of the Oratory and the remains of the convent, before its demolition for the opening of the rue de Rivoli in 1853. Wikimedia Commons

Despite being ignored, Simon was, at times, as rational as any of the philosophes. Indeed, there is something beautifully memorable about Simon’s open-minded analysis; something that reflects the idea that his former home “is a place where the gospel lives in dialogue and is embodied in mutual aid: a Church to think and believe in complete liberty.” Simon longed to dialogue with the Protestants and to reach an accord about the truth of the Gospel. Sadly, in an attempt to find the truth in a middle ground, he ended up alienating Catholics and Protestants alike.

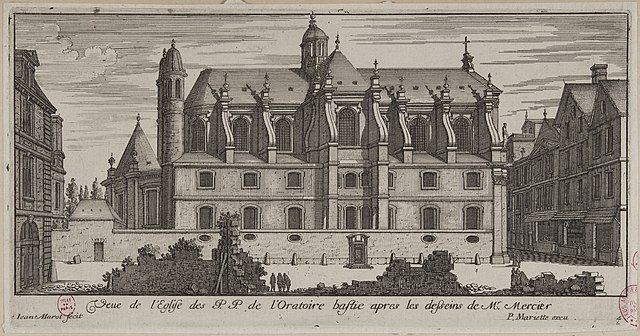

View of the Church of the Fathers from the Oratory built according to the drawings of M. Mercier , etching by Jean Marot (1619-1679), Carnavalet museum

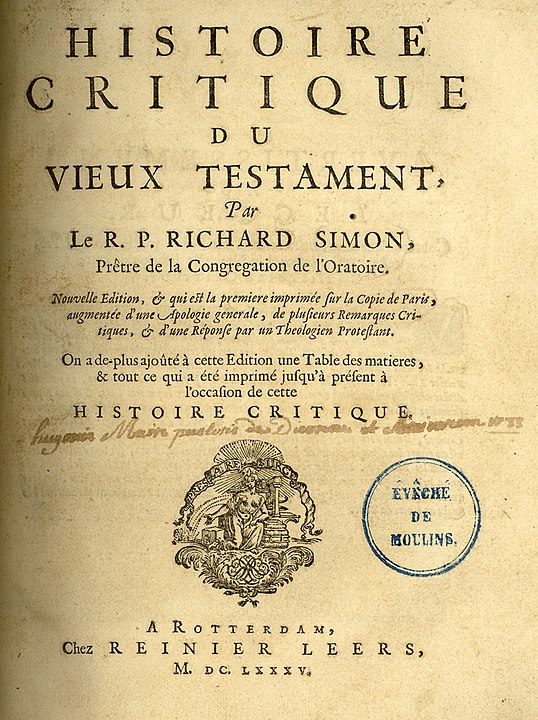

Armed with tremendous erudition and a mastery of biblical languages, Simon concluded that the Bible of his day was flawed: mistranslations, scribal errors, and anachronisms had crept into it, signaling a need for a purer translation, one that recurred to the original languages of the Bible. (He stated, for example, along with the arch heretic Spinoza, that Moses could not have written the end of the book of Deuteronomy because it records Moses’ own death.) His first attempt at ameliorating these corruptions was his most famous work, the Critical History of the Old Testament, known in French as the Histoire critique du Vieux Testament, which was in reality a 500-page prospectus justifying and announcing his upcoming translation of the Old Testament (which he never actually completed).

Protestant temple of the Louvre Oratory. Credit: Emmanuel BRUNNER (Manu25)/ Wikimedia Commons

At the beginning of the work, Simon apologizes for using the word “critique,” which he had to explain since it was so rare. He meant a methodology of study that objectively drew on any available tools to arrive at the original language and meaning of the Old Testament. As naïve as he was brilliant, Simon sincerely thought that Catholics and Protestants, scholars and Church authorities, would agree that the Bible’s impurities necessitated an overhaul in order to return it to the original word of God. He could not have been more mistaken. In fact, two centuries after writing the Critical History, five of his books remained banned by the Church; remarkably, one of them was his French translation of the New Testament.

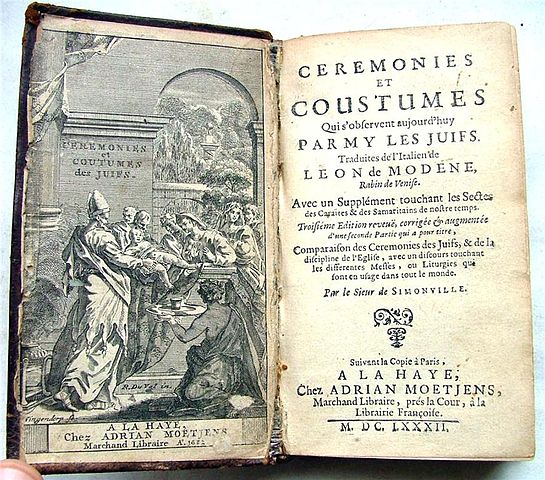

Ceremonies and customs among the Jews of Leon of Modena, translated by Richard Simon, 1682. Credit: Johan Hagadol / Wikimedia Commons

He obediently followed all the channels to receive approval to publish and, in 1678, 1,300 highly anticipated copies were printed in Paris. Within days, the sternly orthodox Bishop Bossuet learned of the book’s thesis and became apoplectic, convinced that the book contained a mountain of impieties and heresies. Bossuet contacted the lieutenant of police in Paris, La Reynie, who set about confiscating all 1,300 copies (a job made easier by the fact that 600 were found at one bookseller’s shop). By the summer of 1678, La Reynie was satisfied that the plague of unorthodox ideas had been contained, and Simon’s work went up in flames in three separate bonfires over three days — a sort of Holy Trinity of fiery censorship.

Except for one copy.

That one copy somehow made its way to Protestant Holland, where it was printed by a Protestant, and smuggled back into Catholic France, where it helped energize the burgeoning field of Biblical criticism. His passionate devotion to truth at the expense of discretion led to a series of scholarly run-ins with Catholic authorities that resulted in Simon banned from the Oratorians. With no place to turn, he returned to his hometown of Dieppe where there is, in fact, a Rue Richard Simon. Sadly, most of his precious library was destroyed in the naval bombardment of 1694 during the Nine Years War.

But his legacy of dialogue lives on in the bold spirit of French criticism and the Protestant church that few visitors notice across the street from the Louvre. And so, perhaps the next time you visit the Louvre, you might take a moment to walk up the Rue de l’Oratoire, admire the beautiful Protestant church, and think of one France’s greatest — and least remembered — intellectuals.

Title page of Richard Simon’s “Critical History of the Old Testament,” 1685. Wikimedia commons

Lead photo credit : Oratoire du Louvre. Credit: Arthur Weidmann / Wikimedia Commons

More in Gaspard de Coligny, Huguenot, Louvre, Oratoire du Louvre, Protestant, Richard Simon, Rue du Rivoli, The smart side of Paris