Introducing Picasso’s Gang with a Tour of their Favorite Haunts

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Apollinaire: The Vision of a Poet at the Musée de l’Orangerie and Cabaret Picasso at the Théâtre Poche-Montparnasse celebrated the infamous bande à Picasso (Picasso’s Gang) in Paris this summer. Unfortunately, these excellent strolls down Modernism’s Memory Lane closed over the Bastille Day weekend. Not to worry, if you planned to be in Paris later this summer—or anytime, really. Bonjour Paris has created for you an exclusive “Picasso’s Gang Tour” (a brief respite from Pokemón Go, PG enthusiasts) that is available all year round – hopefully, in perpetuity. So grab your metro card, a map and your cell phone as we lead you through the streets of Paris, in search of the landmarks that united Picasso and his Merry Pals. (And don’t forget to stop in their favorite cafés for an apéro or two to drink a toast in their honor.)

The Core Members: Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, André Salmon, and Guillaume Apollinaire.

When the 20th century was fresh and new, a notorious group of 20-something avant-gardists changed the course of art history. They revered the Symbolist enfant terrible Arthur Rimbaud and yet rebelled against Symbolist trends. Their mission was to liberate order and bring order to liberation. Although they seemed culturally diverse on the surface, fundamentally they had much in common. Pablo Picasso and André Salmon were sons of artists. Max Jacob descended from a family of tailors and antique dealers. Guillaume Apollinaire belonged to the dramatic life of his mother’s invention. Among their friends and foes, they became a creative force to contend with – a gang of movers and shakers, pranksters, and dedicate disrupters, destined to be the voices of their generation.

Like all self-selected bohemians, they lived a life of modest means – if not downright poverty – by choice, since each man tested out conventional bourgeois occupations early on. The poets Jacob, Apollinaire and Salmon worked in retail, banking and government before they figured out how to survive on their writing. Picasso considered illustration for posters and menus before he fully committed himself to living off his fine art projects exclusively.

Portrait photograph of Pablo Picasso, 1908 / Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais / Public Domain

Pablo Picasso (October 25, 1881-April 9, 1973) was born in Malaga, Spain, the son of a painter and art teacher. His family moved to La Coruña in the northern Spain in 1891 for his father’s job at the local art academy. In 1895, the family settled in Barcelona, home of the hipster-ish modernistas, a tertulia of avant-garde writers and artists who were a bit older than the impressionable Pablo Picasso y Ruiz. They urged him to visit Paris, the garden of revolutionary delights. Finally, in the spring of 1900, Picasso arrived for the first time in this Capital of Art, staying through the fall. He returned in the spring of 1901 to mount an exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery that June. At his own show, he met the poet Max Jacob, five years his senior. They became fast friends and kept up with each other after Picasso’s returned to Barcelona. Back in Paris in 1902, Picasso lived with Jacob in his modest flat on the Boulevard Voltaire. During the day, Picasso slept in their one bed, while Jacob worked in a department store. At night, Jacob slept in the bed, while Picasso painted. Jacob was the first Frenchman whom Picasso truly knew well. They read poetry together and, through Jacob, Picasso learned how to speak French fluently.

Site of Le Bateau-Lavoir / David McSpadden/Flickr / Public Domain

Le Bateau Lavoir, Place Émile Goudeau, 75018 (Montmartre); The original was destroyed in a fire in 1970.

During the spring of 1904, Picasso moved to Paris permanently, setting up his first studio in the filthy, vermin-infested “Bateau Lavoir” (“laundry boat”) – a nickname invented by Max Jacob. Located at 13 rue Ravignan (now Place Émile Goudeau) in Montmartre, the original building burned down in May 1970 and was restored in 1978. Today, the public can visit an attractive storefront on the square that displays memorabilia from the Picasso era. In those days, this part of Paris was quite sleazy and removed from the more upscale bourgeois neighborhoods of their patrons (such as Gertrude, Michael and Leo Stein, whose salon took place at 27 rue de Fleurus, near the Luxembourg Gardens).

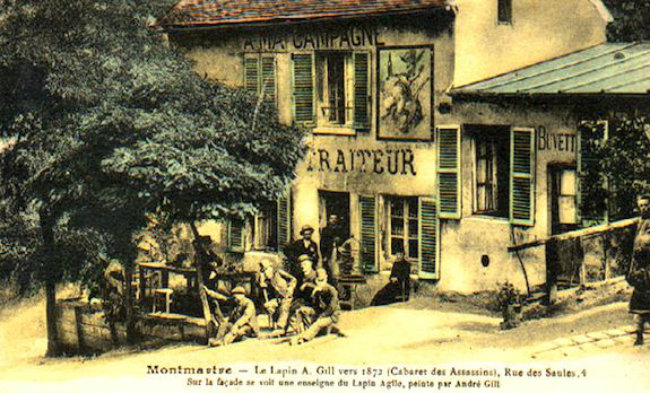

“Au Lapin Agile” Pablo Picasso, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Au Lapin Agile courtesy of charley1965/Flickr

Above his door at the Bateau Lavoir, Picasso wrote in blue chalk “Au Rendezvous des Poètes” (The Poets’ Meeting Place). He invited scores of friends and friends of friends to share in the Gang’s nightly antics (if they weren’t at Frédé’s Lapin Agile, the Closerie de Lilas, Gertrude Stein’s Saturday salons, or Henri Rousseau’s soirées). The famous “Rousseau Banquet” at Picasso’s studio took place in March 1908.

In 1909, Picasso moved to 11 Boulevard de Clichy, with his lady love Fernande Olivier, but kept his paintings stored in the Bateau Lavoir. In September 1912, he moved with his next serious mistress Eva Gouel (aka Marcelle Humbert) to 242 Boulevard Raspail, in Montparnasse, giving up, as well, his studio/storage space in the Bateau Lavoir.

In 1918, Picasso married the Ukrainian ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova and embraced the bourgeois taste his bride brought into the marriage. He was ready to settle down. They lived at 23 rue La Boëtie in a well-appointed apartment on the first floor. Picasso’s reigned over his messy studio on the second. (Eventually it became his refuge as Olga objected to socializing with his old friends from Montmartre.)

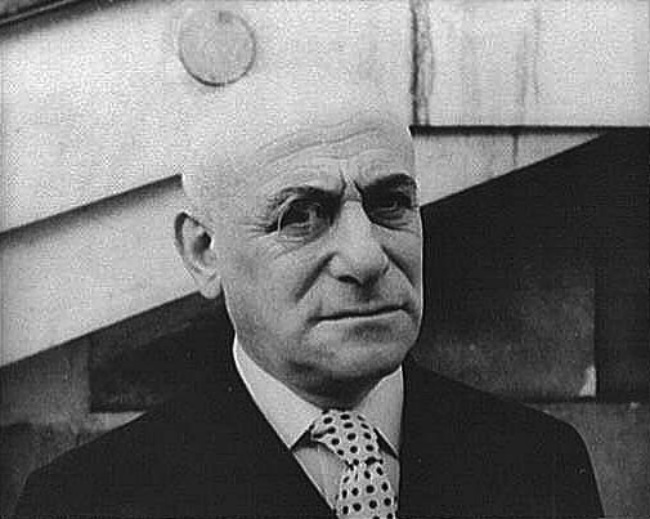

Max Jacob, 1934 / Van Vechten Collection at Library of Congress / Public Domain

Max Jacob (July 12, 1876-March 5, 1944) was born in Quimper, Brittany, the son of Jews who hardly practiced their religion. By 1915, he had converted to Catholicism, after a vision in his apartment in 1909. At his baptism, Picasso became his godfather. Among Picasso’s Gang, he was the best educated in formal terms. Openly gay, Max Jacob’s relationships with his fellow Gang members were strictly platonic.

A poet, painter and gifted mimic, Jacob entertained Picasso’ Gang and their friends with hilarious theatrics and mystical readings. One of their favorite role-playing games was called “Faire Degas” (“Playing Degas”), wherein each artist would pretend to be a grumpy critic – in keeping with Degas’ reputation. The “Degas” impersonator would target one victim who had to defend himself with equally acerbic barbs.

The volley of arch witticisms proved one’s mettle in the eyes of the Gang, much to Picasso’s delight as an observer. (The Cubist-turned-Dada artist Marcel Duchamp told Pierre Cabanne that a conversation with Apollinaire and Jacob was “a series of fireworks, jokes, lies, all unstoppable because it was in such a style that you were incapable of speaking their language.”) Aside from his extraordinary verb skills, Max Jacob cultivated his interests in astrology, Kabbalah and experimental intoxication (mainly ether and opium, the preferred recreational drug among the other members of the Gang).

The installation for The Jester in Picasso Sculpture at the Musée Picasso, photographed by Beth Gersh-Nešić

Both the exhibition about Apollinaire and Picasso Sculpture feature a work based on Max Jacob’s face, The Jester, dated 1905, which Roland Penrose claimed in his 1958 biography of Picasso was modified to such an extent that only the lower part is reminiscent of Jacob’s likeness. (The straight nose and square jaw appear in various figures throughout Picasso’s Rose Period.) Nevertheless, Picasso’s choice of a jester tells us so much about Max Jacob’s relationship with the artist and the other members of Picasso’s Gang.

Jacob died of pneumonia on March 5, 1944 in the Nazi’s internment camp in Drancy, having been arrested on February 24th in the monastery in St. Benoît-sur-Loire, his usual religious retreat. Even though he had converted to Catholicism, he was forced to wear a Jewish star during the Nazi Occupation. Salmon had begged him to live at his home for safe haven, but Jacob refused, confident that the monastery was the better choice of the two.

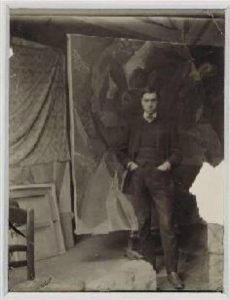

Andre Salmon in front of Picasso’s 3 Woman 1908 / courtesy of Andre Salmon official website

André Salmon (October 4, 1881-March 12, 1969) was the only Parisian of the “gang,” the son of two political activists during The Commune, a short-lived French government from March to May 1871. They lived in London after the fall of the government and returned to Paris before André, their fourth child, was born. His parents’ circle of artistic and literary friends provided young André with most of his education. Salmon’s father Émile Frédéric was an engraver and sculptor who accepted a commission in St. Petersburg, Russia when André was 16. André stayed in Russia after his parents left to watch over his sister Lia, who had become an actress there. He worked for the French consulate until age 21, when he had to return to France for compulsory military service. His expatriate experience in Russia (learning Russian and still keeping up with French literary trends through the consulate’s subscriptions) stayed with Salmon all his life, accounting for his attraction to foreign artists living in Paris, such as the Spanish Picasso, whom he met through the Spanish sculptor Manuel Hugué (known as Manolo) in early 1905. The day after Manolo led Salmon to Picasso’s studio, he returned to continue the conversation and found Max Jacob standing on the threshold about to go through the door. They introduced themselves to each other and became the closest friends among the foursome.

Le Depart Saint-Michel, 1 place Saint Michel, Paris / Public Domain

Le Caveau de Soleil d’Or (today: Le Départ)

By then, Salmon and Apollinaire had been a creative team for nearly two years. They met in April 1903 in the Caveau du Soleil d’Or, which is now Le Départ on the Boulevard Michel. At the time it was the hang out for associates of the literary magazine La Plume. Salmon was living in a flat at 244 rue Saint Jacques, his first residence after a short stint in the army. From this apartment the two poets founded and edited (with fellow writers Jean Mollet and Nicolas Deniker) their first literary magazine Le Festin d’Esope (Aesop’s Feast), a reference to the storyteller’s legendary meal of tongues, source of the best and worse that humankind can offer. It served as the launch pad for their nimble minds.

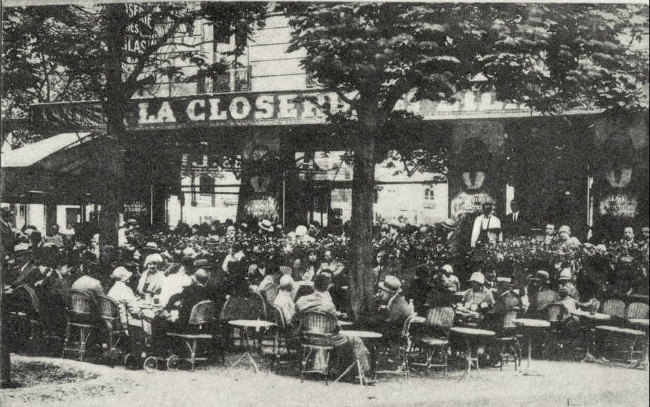

La Closerie des Lilas en 1909 / Public Domain

View of the brasserie/restaurant La Closerie des Lilas at boulevard du Montparnasse in Paris / Public Domain

La Closerie des Lilas, 171 Boulevard de Montparnasse, 75006

Salmon also assumed the role of secretary for Paul Fort’s literary journal Vers et Prose. This literary group met at the Closerie des Lilas in Montparnasse.

In 1905, Salmon published his first book, Poèmes, accompanied by Picasso’s caricature of his new friend, the first of several collaborations. By 1907, Salmon also lived in the Bateau Lavoir. That year, he witnessed Picasso’s months of laborious work to complete his masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which Salmon named just before installing the painting in his 1916 exhibition “L’Art Moderne en France,” or Le Salon Antin, inside the designer Paul Poiret’s Galerie Barbazanges, 109 rue du Faubourg St. Honoré (July 16-31; 100 years ago this summer). No one outside of Picasso’s intimate group of friends had seen his “philosophical brothel” for all those nine years. It was the Demoiselles’ debut. (Today, these five Gorgon-esque ladies are permanently on view at the Museum of Modern in New York City.)

St. Merri Church, exterior with Nikki de Saint-Phalle and Yves Tanguy sculptures / Public Domain

St. Merri Church, interior / Beth Gersh-Nesic

Salmon moved out of the Bateau Lavoir in 1909 to settle down with his bride on rue Rousselet, not far from the boulevard Montparnasse. He married Jeanne Blazy-Escarpette, a model, on July 13th in St. Merri Church. The nuptials purposely coincided with the day before Bastille Day in order to take advantage of the festivities that evening in the streets all over Paris. On the way to the church, Guillaume Apollinaire composed his famous “Poem Read on André Salmon’s Wedding Day,” first published (with some modifications) in Vers et Prose in 1911 and then included in Apollinaire collection of poems, Alcools, 1913.

Nous nous sommes rencontrés dans un caveau maudit

Au temps de notre jeunesse

Fumant tous deux et mal vêtus attendant l’aube

We met in a dive

In the flower of our youth

Smoking together in our shabby clothes, awaiting the dawn.

Picasso. “Apollinaire in Picasso’s Studio at 11, boulevard de Clichy, fall 1910.” Enlarged through photographing for a new negative by Dora Maar, circa 1937-1940, silver-gelatin print, 23.7 × 17.9 cm. Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso.

Guillaume Apollinaire in Picasso’s studio, 1910

Guillaume Apollinaire (né Guglielmo Alberto Wladimiro Alessandro Apollinare de Kostrowitzky or Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary Kostrowicki, August 26, 1880-November 9, 1918), came into this world in Rome, the son of a Polish minor noblewoman, Angelika de Kostrowicka, and an unknown father (perhaps the Swiss officer Francesco Costantino Camillo Flugi d’Aspermont). Like the other members of Picasso’s Gang, his life had been “exotic” in comparison to most Parisian denizens. Although his mother moved her two sons several times, Apollinaire managed to weather the disruptions in his French education and excel in writing. Apollinaire’s extraordinarily inventive mind produced the poetry of circumstance, the intersection of modern life and personal emotions, which made him one of the leading lights in French literature. Picasso met Apollinaire in an English bar, perhaps Fox’s, in early 1905. The bande à Picasso was complete from then on.

Apollinaire, Salmon, Jacob and Picasso galvanized their fellow artists toward the greatest revolution in art history: Cubism. Their contributions to the movement include overlapping one’s personal life, objects and current events (such as, sex, death and popular music) to achieve the sensation of simultaneity. We can see their ideas in Picasso’s collages (1912-1914), Salmon’s long prose-poem A Manuscript Found in a Hat (1905-1919), Max Jacob’s puns, and Apollinaire’s whimsical calligrammes. Their goal was to meditate on time (“the fourth dimension”) in relation to perceptual ambiguities (think of Picasso’s newspaper clippings glued next to fragmented “guitars” and snippets of songs that collectively conjure up their experience of a café). The skeptical critics, however, focused on Picasso and Georges Braque’s geometric planes and branded the movement “Cubism,” which took off in another direction.

Apollinaire and Salmon’s contributed to Cubism through their respective art criticism in L’Intrangeant, Paris Journal and Gil Blas. Salmon placed Picasso’s 1907 bordello Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at the beginning of Cubism. He was the first critic to recognize its artistic merits in his 1912 book Young French Painting. Apollinaire dubbed Picasso’s work “Scientific

Cubism” (the “purest” form of Cubism) in his 1913 book The Cubist Painters: Esthetic Meditations, one of many efforts that testify to Apollinaire’s substantial influence on the art world during his lifetime and afterwards.

Apollinaire’s grave in Pere Lachaise / Public Domain

While these art critics supported Picasso’s career, the artist recorded their aging faces in various finished drawings, sketches, scribbles and letters to the front during World War I. Nearly ten years after Apollinaire died of influenza on November 9, 1918 (two days before the Armistice), a committee formed to commission a suitable memorial sculpture. Picasso was the obvious choice for the job and he responded with a series of maquettes (sculpted sketches) that shaped three-dimensional space within a network of fused black wires. The structural configuration seemed to concretize Apollinaire’s description of “the profound nothingness of poetry and fame” fashioned for his protagonist’s memorial in his quasi autobiographical novella The Assassinated Poet (1916). However, the committee rejected Picasso’s ideas and chose another solution for the grave site in Père Lachaise.

Pablo Picasso, maquette for Apollinaire Memorial, c. 1928; MP 264, Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso. (©Photo RMN-Bétrice Hatala).

Today, the Apollinaire memorial maquettes are on view in the Picasso Sculpture show at the Musée Picasso through August 28th.

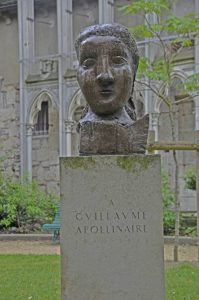

Eventually, Picasso’s Head of a Woman [Dora Maar] was chosen by Jacqueline Apollinaire and unveiled on June 5, 1959 in Laurent Prache Square, behind the Church at St. Germaine-des-Prés, more than 40 years after the death of the poet. Referred to as the Memorial to Apollinaire, it symbolizes Poetry. Apollinaire never met Dora Maar, who was Picasso’s mistress from 1936 to 1944. (Coincidently, as a parting gift, Picasso gave Dora a portrait of Max Jacob, the second loss for the bande à Picasso.)

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Dora Maar), 1941, Laurent Prache Square behind St. Germaine-des-Prés Church, dedicated in 1959.

Only Apollinaire was buried in Paris. Max Jacob was buried in St. Benoît-sur-Loire. Picasso and Salmon died in the south of France, where they both retired: Picasso in Mougins on April 8, 1973; Salmon in Sanary-sur-Mer on March 12, 1969. Picasso is buried on the grounds of the Château de Vauvenargues, which was opened to the public in 2008.

Apollinaire’s death marks the end of Picasso’s Gang as we remember it here. Picasso, Salmon and Jacob remained friends for most of their lives. (Picasso and Salmon had a serious falling out in 1936, which ended in 1950.) The 1959 ceremony marks the last collaborative effort among the surviving members of Picasso’s Gang. Salmon delivered a speech, which he was too overcome to finish. Picasso’s absence spoke memorably on his behalf.

***

For further information about the exhibitions and cabaret spectacle celebrating Picasso’s Gang, please visit these websites:

- Apollinaire: The Vision of the Poet at the Musée de l’Orangerie

- Rousseau: An Archaic Candour at the Musée d’Orsay

- Cabaret Picasso at the Théâtre Poche-Montparnasse.

Image Credits: Au Lapin Agile courtesy of charley1965/Flickr, Andre Salmon in front of Picasso’s 3 Woman 1908 / courtesy of Andre Salmon official website, All other images courtesy of Public Domain.

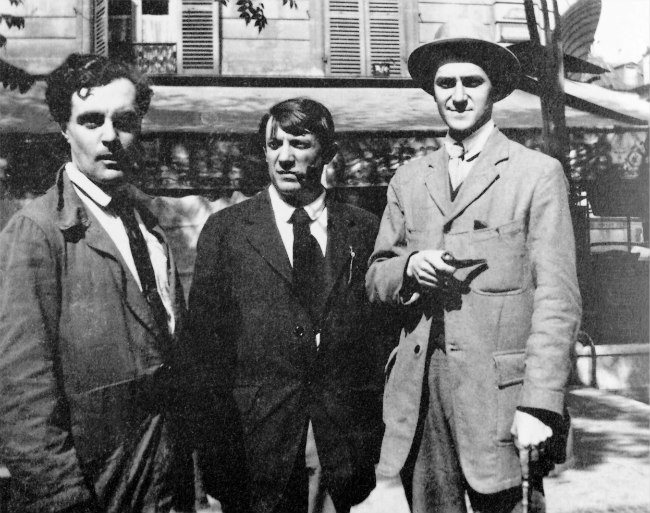

Lead photo credit : Modigliani, Picasso and André Salmon in front the Café de la Rotonde, Paris. Image taken by Jean Cocteau in Montparnasse, Paris in 1916 / Modigliani Institut Archives Légales, Paris-Rome / Public Domain

More in Apollinaire, Art, art and culture, French Art, French artists, French history, picasso

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY