Apollinaire, the Vision of the Poet at the Musée de l’Orangerie

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Marie Laurencin (Paris, 1883- Paris, 1956), Apollinaire and his Friends, 1909; aka A Reunion in the Country,

oil on canvas, 130 x 194 cm, Paris, Centre Pompidou. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Claude Planchet © ADAGP, Paris 2016.

Paris bursts into color every spring and summer as museums open their fresh bouquets of special temporary exhibitions. The 2016 art season is especially exciting with its trio of early modernist shows that weave together the life and legacy of poet, novelist, playwright and art critic, Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918). At the Musée de l’Orangerie, Apollinaire: Le Regard du Poète (The Vision of the Poet) captures the breadth of this extraordinary talent, whose social networking among visual artists surely influenced the Cubist Epoch and contributed to Surrealism.

Apollinaire’s magic (“J’émerveille,” he would say) came from his appetite for life, love and art. He was a true bon vivant – open to adventure and amazement. As you enter the exhibition a map of Apollinaire’s connections to writers, artists and dealers provides a visual diagram of the numerous people represented in the show, either through their own creations or memorabilia.

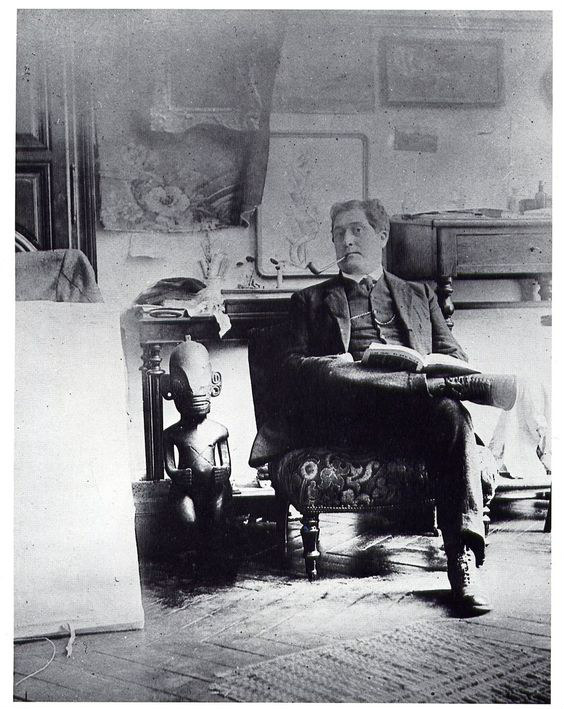

Picasso. “Apollinaire in Picasso’s Studio at 11, boulevard de Clichy, fall 1910.” Enlarged through photographing for a new negative by Dora Maar, circa 1937-1940, silver-gelatin print, 23.7 × 17.9 cm. Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso.

Stout and sturdy, Guglielmo Alberto Wladimiro Alessandro Apollinare de Kostrowitzky or Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary Kostrowicki (aka Guillaume Apollinaire since 1899) was born in Rome to the Polish noblewoman Angelika Kostrowicki, whose survival tactics as a member of the “demi monde” gave her two sons (Wilhelm and Albert)– a colorful existence from day one. Their father remains unknown. Some sources claim it was Francesco Costantino Flugi d’Aspermont, Swiss aristocrat and Italian officer, who maintained a liaison with Angelika through 1885. The de Kostrowitzky family spoke French, Italian and Polish. While migrating from Italy to Monaco to Nice to Paris, the children immersed themselves in their studies at various schools. Wilhelm, as early as high school, devoted himself to writing. In 1914, he became a French citizen in order to enlist in the army to defend France during World War I.

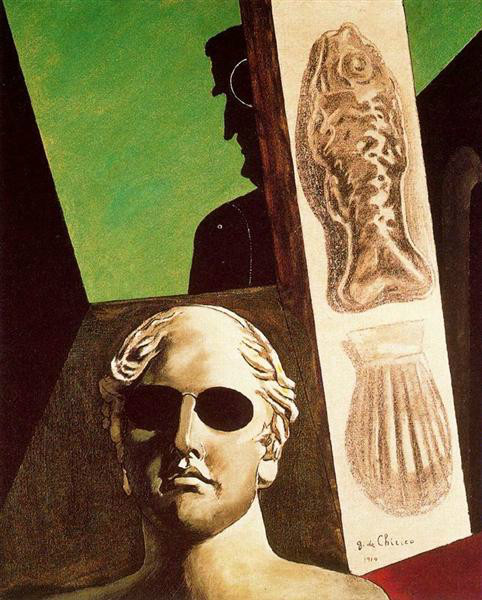

Giorgio de Chirico, Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire,

April-June 1914, oil on canvas and charcoal, 81.5 × 65 cm Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle. ©Centre Pompidou. MNAM-CCI, Distri. RMN – Grand Palais,/Adam Rzepka ©ADAGP Paris 2015.

Among an abundance of portraits, the most haunting and uncanny is Giorgio di Chirico’s, painted in 1914, where we see a circle drawn on the left temple of the black silhouette – foreshadowing the wound Apollinaire sustained on his right temple, two years later, during the Great War. Apollinaire survived this wound, but died two years later at 38 on November 9th. Somewhat weakened in constitution, he succumbed to the Spanish Flu two days before the Armistice on November 11, 1918 (Veteran’s Day in America). As his friends paid their respects to his widow, Jacqueline, crowds outside chanted “A bas, Wilhelm/Guillaume” – referring to the Kaiser’s defeat. The coincidence invaded their grief and proved indelible in their collective memories.

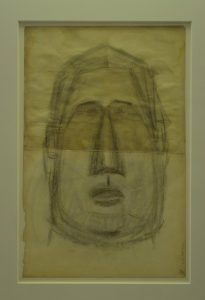

Pablo Picasso, Head (Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire in two parts), August 1908, Charcoal, 48.9 × 63.5 cm. Paris, Musée national Picasso. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée Picasso de Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2016.

How does one sufficiently honor the life of a writer in visual terms? For the chief curator Laurence des Cars and her team, the answer filled seven rooms, each dedicated to a particular theme. Rooms 1 and 2: “L’Homme-Epoch” (translated as “Man-Epoch,” but I would say “the Man and his Moment”) tackles the biographical information, printed on the walls in Room 2. Here art and artifacts illustrate the written word.

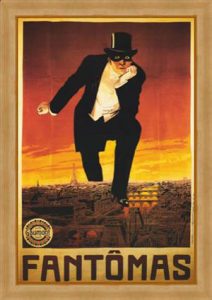

Room 3: “An Unfettered Vision” attempts to encapsulate Apollinaire’s appreciation for a wide range of aesthetics: traditional academic art, antiquity, the avant-garde, African art, puppets, and the latest trends in popular culture. For example, the poster for the film Fantômas represents this 1911-13 series of books and films about a serial killer, which completely enthralled the poet and his gang. According to his close friend and colleague, poet/art critic André Salmon, Apollinaire proposed the idea for the Société à Fantômas, of which they, Picasso, Max Jacob, and Juan Gris were members. In this respect, the group’s desire to integrate high and low art laid the foundation for Pop art, which took off 50 years later.

Anonymous, Poster for the film Fantômas, 1913

Room 4: “Aesthetic Meditations” (the title of Apollinaire’s 1913 book on Cubism) opens up into an enormous gallery subdivided into various sections that represent the complexity of the modern movements he supported in his critical essays. Much in evidence are the Cubists whom he sorted into four categories: Scientific, Physical, Orphic and Intuitive. Examples of works by Picasso, Braque, Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and Marie Laurencin illustrate his thesis.

Room 5: “Apollinaire and Picasso” traces the relationship between the Spanish artist and multinational writer. Here the infamous story of Apollinaire’s arrest and detention in conjunction with the Mona Lisa theft in August 1911 reminds us of the ups and downs of this fruitful friendship.

Jean Metzinger, Study for a Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire, 1911, charcoal on pink laid paper, 48 x 3.2 cm. Paris, Centre Pompidou. ©MNAM – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP© ADAGO, Paris

On display is the letter composed by friends, demanding Apollinaire’s release from the jail La Santé. Picasso was brought into the police station for questioning and denied knowing anything about Apollinaire and the stolen heads (which he had purchased from Apollinaire’s swarmy “secretary” Géry Pieret).

Despite this traumatic experience, which inspired the poem “A la Santé,” published in Alcool (1913), Apollinaire pretended that this betrayal never occurred. Their friendship endured, evidenced by Picasso’s pencil drawing of Apollinaire with his bandaged head in 1916.

Room 6: “The Clock of the Tomorrow” organizes Apollinaire’s numerous projects and involvement with that of others. Marc Chagall’s kaleidoscopic Homage to Apollinaire, 1912-1914, expressionistically conveys the fecundity of Apollinaire’s touch. On the lower left, we see a heart pierced by an arrow surrounded on four sides by the names of Apollinaire, poet [Blaise] Cendrars, [Georg] Lewin, and [Herwarth] Walden (the pseudonym for Georg Lewin, founder of the gallery and review Der Sturm). All three advocated for the avant-garde as far as their spheres of influence allowed.

Pablo Picasso, Apollinaire in Profile with Bandaged Head, 1916, graphite pencil and conté crayon on thick vellum paper, 31.3 x 23.1 cm, Acquition, 1993, MP 1993-5, © Succession Picasso 2016.

Print : RMN Grand Palais / René-Gabriel Ojéda.

Marc Chagall, Homage to Apollinaire, 1912-14

Einhoven, Collection von Abbemuseum

©Peter Cox, Einhoven, The Netherlands

©ADAGP, Paris 2016

Here too we discover the American artist Cecil Howard’s colorful sculptures and sketches for the Apollinaire’s satirical play Les Mamelles de Tirésas (written in 1903 and produced in 1917), wherein he used the word “surrealist” for the first time to describe his intention.

Howard’s work belongs to a private collection, along with so many other objects, known and unknown gems, that tell us about Apollinaire’s life. Moreover, it is tremendously educational to see these works of art from different countries converging and conversing in tribute to a man who demonstrated an insatiable curiosity throughout his all too brief career.

Cecil Howard, Guitarist, c. 1913-1918

Polychrome wood, 17 x 25 x 13 cm.

Collection Yves Belleyton

And let us not forget Apollinaire’s ingenious Calligrammes: Poems of War and Peace, written from 1913 to 1916, and published in 1918. Here in the sixth room we see the originals in his own hand, the very reason most of us decided to visit this show. The calligrams respond to the 1912-14 Cubist collages’ simultaneous interplay of word, image and multiple meanings. Apollinaire too explored simultaneity in these linguistic and visual terms that set up a tension between typography and iconography. These thoroughly inventive treasures still enchant us today over one hundred years later. They are among the marvelous in Apollinaire’s claim to “émerveiller.”

Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligramme poem for Lou, sent by Apollinaire to Louise de Coligny-Châtillon, 9 February 1915, ink and colored pencil on paper, 20.8 × 14.8 cm. Private Collection. © Musée d’Orsay / Patrice Schmidt

Room 7: “Apollinaire and Paul Guillaume” completes this retrospective, testifying to an unusual friendship between two generations. The fledging art dealer Guillaume was only 18 years old when he met the 31 year old Apollinaire in 1911. They worked together on several projects, most notably the first Matisse-Picasso exhibition in 1918.

Guillaume’s collection belongs to the Musée de l’Orangerie, which accounts for the appropriateness of this venue. The Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Guillaume: Correspondance (1913-1918), Gallimard, 2016 (edited by Peter Read, professor of literature and visual art at the University of Kent in the UK, and Laurence Campa, professor of modern literature, University of Paris-East, Marne-la-Vallée) shares their letters with the general public.

On May 18th, Read and Campa presented the story of Apollinaire and Guillaume through an oral reading of these letters performed by two actresses and accompanied by the scholars’ equally dramatic narratives that contextualized the Apollinaire-Guillaume exchanges.

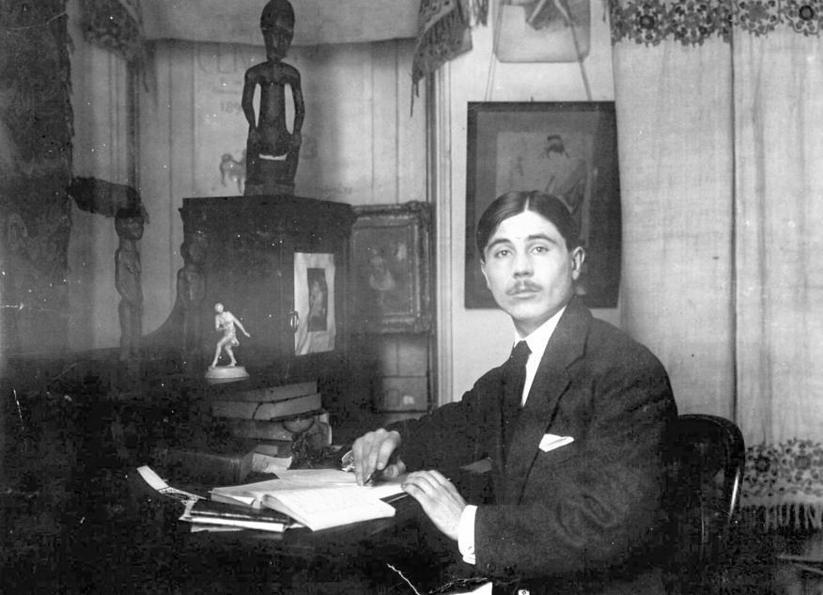

Paul Guillaume in his first gallery, in 1914

© RMN-Grand Palais / Fonds Alain Bouret – Musée de l’Orangerie

However, all the works that pertain to Apollinaire’s life are not in the Musée de l’Orangerie. For example, Henri Rousseau’s The Muse Inspiring the Poet (Apollinaire and his lover at the time, Marie Laurencin), 1909, can be found cross the Seine at the Musée d’Orsay, in this autodidact’s retrospective Le Douanier Rousseau: Archaic Candour.

Henri Rousseau, The Muse Inspiring the Poet, 1909 (first version). Oil on canvas, 131 x 97 cm. Moscow, Pushkin Museum.

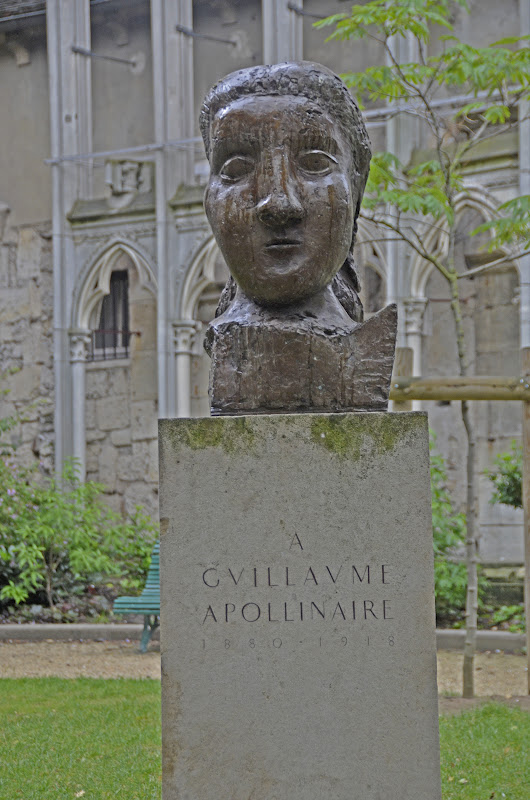

And the various maquettes for the Apollinaire Memorial are on view in the temporary exhibition Picasso Sculpture at the Musée National Picasso, a bit farther away in the Marais. All these miniature models failed to meet the approval of the Apollinaire Memorial Committee. Eventually, The Head of a Woman (a portrait of Dora Maar) satisfied the demand for a traditional figurative marker. It was not placed by Apollinaire’s grave, but instead in Laurent Prache Square behind St. Germaine-des-Prés Church. Dedicated in 1959, over 30 years after Picasso was commissioned by the committee, the head was randomly selected in Picasso’s studio by Apollinaire’s widow Jacqueline. The wiry metal sculpture reflects Picasso’s attempt to interpret Apollinaire’s description of a memorial created for his character the dead poet Craniamanal by the artist Bird of Benin [based on Picasso], in The Assassinated Poet (1916), “a profound nothingness, like poetry and fame.”

A visit to Laurent Prache Square supplements the exhibition Apollinaire: Le Regard du Poète, on view through Monday, July 18th.

Pablo Picasso, maquette for Apollinaire Memorial, c. 1928; MP 264, Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso. (©Photo RMN-Bétrice Hatala).

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Dora Maar), 1941, Laurent Prache Square behind St. Germaine-des-Prés Church, dedicated in 1959.

Apollinaire: Le Regard du Poète is a curatorial collaboration among the Musée de l’Orangerie, the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre George Pompidou, the Musée National Picasso, and the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. The catalogue Apollinaire : Le regard du poète is a co-production of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie (Paris: Gallimard, 2016). It features essays by the chief curator Laurence des Cars, Émilie Bouvard, Laurence Campa, Cécile Debray, Peter Read, Maureen Murphy, Claude Debon, Claire Barnardi, Didier Ottinger, Carole Aurouet, Henri Soldani, Étienne-Alain Hubert, Cécile Giraudeau, Émile Bouard and Émilia Philippot, Jean-Jacques Lebel, and Sylphide de Daranyi.

***

The opportunity to visit all three exhibitions within a reasonable distance continues through July 17. For more information, please consult the websites of each museum:

Apollinaire: Le regard du poète, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, April 6 – July 18.

Le Douanier Rousseau: Archaic Candour, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, March 22 – July 17.

Picasso Sculpture, Musée National Picasso, Paris, March 8 – August 28.

Lead photo credit : Picasso. "Apollinaire in Picasso’s Studio at 11, boulevard de Clichy, fall 1910." Enlarged through photographing for a new negative by Dora Maar, circa 1937-1940, silver-gelatin print, 23.7 × 17.9 cm. Paris, Musée national Picasso. ©Session Picasso.