Beyond the Lilies: The Collection at the Musée de l’Orangerie

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In the Jardin des Tuileries, overlooking the Place de la Concorde, stand two buildings in neoclassical style. After serving various functions, the Jeu de Paume exhibits modern and contemporary art. The Musée de l’Orangerie once sheltered the garden’s orange trees in winter; today it houses Claude Monet’s final, most monumental work.

In the Jardin des Tuileries, overlooking the Place de la Concorde, stand two buildings in neoclassical style. After serving various functions, the Jeu de Paume exhibits modern and contemporary art. The Musée de l’Orangerie once sheltered the garden’s orange trees in winter; today it houses Claude Monet’s final, most monumental work.

The Nymphéas – the waterlilies of Giverny – were a recurrent theme in Monet’s oeuvre. This series of eight panels, painted as a memorial to those who died in World War I, stayed with Monet until his death in 1926. According to his wishes, they are now displayed under direct but diffused natural light in two adjoining oval rooms, creating a total environment. In 1927, the Nymphéas opened to the public and remain an obligatory destination for visitors to Paris.

A visit to the museum’s lower level reveals a fine collection of 19th and 20th-century paintings. The story of how they ended up there has all the elements of a roman de gare – a femme fatale, illicit passions, black-market babies, forgery, attempted murder and blackmail. It begins with two people who reinvented themselves in Paris.

Paul Guillaume was of modest background, but his social ambitions propelled him into the avant-garde of Parisian art. Through his friendship with Apollinaire, he met the artists he represented and collected, and he sold them African art. Dr. Albert Barnes bought from Paul, who dreamed that one day his own museum would surpass The Barnes Collection.

Paul Guillaume was of modest background, but his social ambitions propelled him into the avant-garde of Parisian art. Through his friendship with Apollinaire, he met the artists he represented and collected, and he sold them African art. Dr. Albert Barnes bought from Paul, who dreamed that one day his own museum would surpass The Barnes Collection.

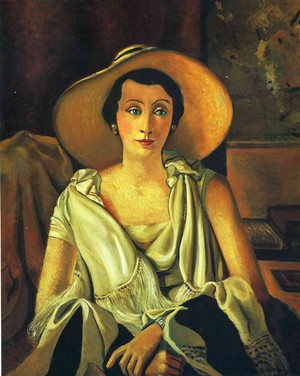

Domenica Guillaume (née Juliette Lacaze in Milau) was not a great beauty (she was said to resemble the actress Joan Crawford), but she attracted a succession of well-connected men, including a prime minister. As ruthless as she was seductive, she stopped at nothing to get what she wanted.

One of her more enduring affairs was with Jean Walter, an architect. His considerable fortune came from a mine in Morocco that proved to be a rich source of lead and zinc. Walter was married and the father of three, by all accounts a decent man. Although he was troubled by the affair, Paul genuinely liked Walter. For a time, the three lived in the same apartment building.

In 1934, Paul Guillaume died of septic shock caused by appendicitis or an ulcer. What is certain is that he didn’t receive the necessary medical treatment until too late. He was 43 years old. No will was found, but Paul had made clear his intention that, absent children born of the marriage, his collection should go to the Musée du Luxembourg. (A handwritten will later surfaced. Paul and Domenica had very similar penmanship.)

In the face of losing her inheritance, the widow rose to the occasion, stuffing a pillow under her dress to fake a pregnancy. As her supposed due date approached, she left town, returning with a baby boy purchased from a trafficker. Her unfortunate victim would be named Jean-Pierre Guillaume, and his adoptive mother showed him a living hell. While she lived in luxury on rue du Cirque, Jean-Pierre never had a bedroom, sleeping instead beneath the dining room table. When Domenica entertained, he was banished to the bathtub. Domenica berated and deprived him. If he needed shoes, she would give him only one, making him earn the other.

Walter’s first wife died, and he and Domenica married in 1941. As in her first marriage, Domenica’s affairs continued. Dr. Maurice Lacour was 15 years her junior and a particularly nasty piece of work. He was a right-wing extremist with dubious medical credentials and an expert in poisons, valued by certain socialites for his willingness to prescribe drugs.

Walter’s first wife died, and he and Domenica married in 1941. As in her first marriage, Domenica’s affairs continued. Dr. Maurice Lacour was 15 years her junior and a particularly nasty piece of work. He was a right-wing extremist with dubious medical credentials and an expert in poisons, valued by certain socialites for his willingness to prescribe drugs.

In 1957, Jean Walter was injured in a hit-and-run accident. Domenica and her lover refused an ambulance and drove him themselves to the hospital. He was dead upon arrival. Another inconvenient spouse had expired under questionable circumstances, and Domernica’s wealth increased. While there was talk, no charges were ever brought against her.

Jean-Pierre fled his miserable home and served as a paratrooper in Algeria. Upon his return to Paris, he was approached by Camille Rayon, a dashing former paratrooper and Resistance hero with an incredible story to tell.

Faced with the possibility that Jean-Pierre would claim his inheritance, Domenica and company conspired to have him eliminated. Domenica’s brother, Jean, had solicited Rayon to do the dirty deed. Rayon needed the money, but his code of honor prohibited harming a fellow warrior. He surmised the family would do anything to avoid a scandal, and so he strung them along, pretending to agree to the plan. He warned Jean-Pierre, and, ultimately, the police were brought in. Lacour spent several months in jail; Jean Lacaze was out in a few days. Domenica, the obvious mastermind, was never even charged.

Domenica’s connections in high places had paid off, as did her prized collection – works by Renoir and Cézanne, Modigliani and Matisse, Picasso, Derain, Soutine and more – that could easily fetch a billion dollars at market. Domenica lacked Paul’s acumen as a collector and sold seminal works to finance “safe” art. Thus, the collection shows Paul was a discerning collector, but fails to confirm him as a pioneer.

The Jean Walter-Paul Guillaume Collection was sold to the state for a pittance. Conventional wisdom held that Domenica had bought her freedom.

If you’d like to read more, Monet Or The Triumph Of Impressionism will give you added insights.

(Images: Monet’s Nymphéas, Musée de l’Orangerie; Portrait of Paul Guillaume by Amadéo Modigliani; Portrait of Domenica Guillaume by André Derain)

Jane del Monte lived for a number of years in Paris. She is the owner of ARTS in PARIS, tours with a focus on French culture and art de vivre.

More in Musée de l’Orangerie, Museum, Paris art museums, Paris museums, Paul Guillaume