Henri Matisse at 150: Art as Comfy as an Easy Chair

“What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art which could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

—Henri Matisse, “Notes from a Painter,” La Grande Revue, LII, 24, 25, December 1908, pp. 481-485. (Translated in Matisse on Art, editor Jack D. Flam, E.P. Dutton, 1973)

Nothing could be more welcome than a well-organized and “comfy” retrospective of Henri Matisse’s career during this dreadful Covid-19 pandemic. We need these bright colors and voluptuous shapes. Unfortunately, Centre Pompidou’s Matisse, Comme Un Roman, a perfect choice for our anxiety-ridden times, closed down almost as soon as it opened on October 21, 2020. I imagine the soul of Henri Matisse wondering through the beautifully installed galleries, devoid of visitors, inhaling and exhaling in long, drawn out sighs . . . “Ugh! Picasso has had multiple exhibitions all over the world every single day. Now that it is my turn, this once-in-a-lifetime retrospective of 230 artwork and 70 documents, is shuttered until the first week of the New Year. Zut! But wait – Picasso’s whole museum in Paris is closed. Bon! But then, that means my museum in Le Cateau-Cambrésis is closed too! Curses!”

As of this writing, the French museums will remain closed through January 7, 2021. In the meantime, you can access podcasts and a video tour on the Centre Pompidou website here. Let’s hope Matisse’s exhibition will brighten the New Year before its scheduled closure on February 22nd.

Matisse on art Jack Flam, cover of 1995 edition. Part of series Documents on Twentieth-Century Art (University of California, 1995)

New Year’s celebrations are an integral part of Matisse’s life story. He was born at 8 pm on December 31, 1869, four hours before the dawn of France’s highly transformative year and decade. The first child and first son of a prosperous grain merchant Émile-Hippolyte-Henri Matisse and his artistically-gifted milliner wife, Anna Héloïse Gérard, Henri-Émile-Benoit Matisse came into the world while his parents were spending the holidays with family in Le Cateau-Cambrésis. At the time, they lived in Bohain-en-Vermandois, Picardy.

By the next fall, this joyous family would see their government, the Second Empire under Napoleon III, collapse during the Franco-Prussian War (July 19, 1870 through January 28, 1871). By the end of May 1871, the short-lived Paris Commune would be defeated and a more conservative government would take charge. In the wake of this tumultuous period, a bunch of 30-something artists would form the avant-garde modernist group called the Anonymous Society of Painter, Sculptors and Engravers, sarcastically dubbed the “Impressionists” by their unimpressed critics. As Matisse came of age several transgressive movements challenged acceptable art conventions. In time, Matisse would become the leader of their progeny, the Fauves (Wild Beasts).

At the Centre Pompidou, a most august pillar of French culture, we ironically celebrate one of the most ferocious of these excoriated “Wild Beasts” with a spectacular 150th birthday retrospective, culled from collections all over France and some abroad, and thoughtfully organized by the museum’s curator Aurélie Verdier, who helps us discover the literary side of Matisse’s creations. Inspired by Louis Aragon’s Henri Matisse, roman (1971), she divided the artist’s life into “nine chapters,” each introduced by a well-known contributor to the arts: Louis Aragon, Georges Duthuit, Dominique Fourcade, Clement Greenberg, Charles Lewis Hind, Pierre Schneider, Jean Clay, and Henri Matisse himself. The curator’s tour is available on the Centre Pompidou website and on YouTube.

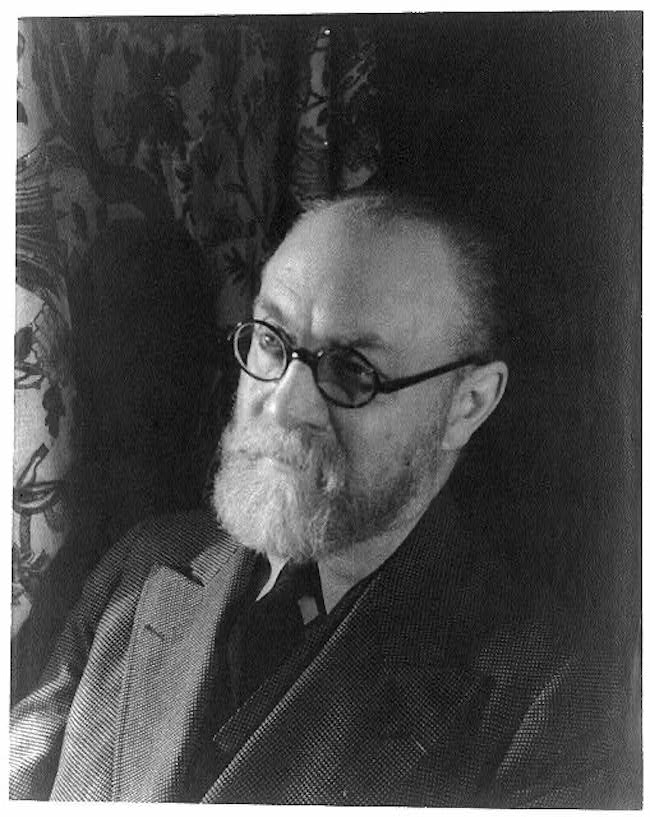

Portrait of Henri Matisse in 1933. Taken by Van Vechten, Carl, 1880-1964, photographer. Photo credit © Carl Van Vechten Photographs, Picryl

Who was Henri Matisse, the alleged promoter of comfy furniture painting? In fact, he was quite the rebel in a tweed jacket, bespectacled, conventionally bourgeois, and slightly nerdy compared to his contemporary avant-garde companions, who clung to every word of his serious theoretical explanations. He transformed pure color into “A Block of Light, 1904-5,” the second gallery that showcases the height of his Fauvist years.

Oh, Henri, you fooled us, didn’t you, with your oft-misquoted “armchair” philosophy? You didn’t mean to extol banal decoration, but instead you invented screaming hues of red, blue, yellow, and green, composed in environments occupied by unconventionally proportioned human bodies or floral designs. You incessantly irritated your critics and shocked the general Parisian art salon crowd. Comforting and “soothing” you were not, back then. Are you today? For most of us, yes. For you are the great painter of the modernist movement, a bygone period of optimism we hope to retrieve each time we bask in the radiance of your light. And your influence still shines brightly on our current young masters, most notably Kerry James Marshall and Mickalene Thomas, among others, just as your light supported the emergence of the École de Paris and its satellites, such as Marc Chagall, Jacqueline Marval and Jules Pascin.

A sustained careful study of your artistic trajectory, Henri, from Gustave Moreau’s studio to the paper cuts created shortly after your near death from cancer in 1941 (you lived 13 years more), reveals unmistakable moments of relentless struggles to achieve your desired goals, your “condensation of sensations”:

“Both harmonies and dissonances of color can produce agreeable effects. Often when I start a work I record fresh and superficial sensations during the first session. . . I want to reach that state of condensation of sensations, which makes a painting. I might be satisfied with a work done at one sitting, but I would soon tire of it; therefore, I prefer to rework it so that later I recognize it as representative of my state of mind.” (from Matisse on Art, 1973)

This distillation of your truth, augmented by your attraction to Henri Bergson’s concept of “intuition” (the latest art philosophy at this time) guided your visual vocabulary of personal signs, as you remarked to Louis Aragon during his 1943 interview:

“The importance of the artist is measured by the quantity of new signs he will have introduced into the language of art (le language plastique).”

(From “Matisse-en-France,” published in Henri Matisse: Themes and Variations (1943), and repeated in Aragon’s Matisse, roman /Matisse, Novel, 1971.)

Henri Matisse, Interior with Aubergines, 1911, tempera on canvas 212 x 246 cm (83. 46 x 96.85 inches) Musée de Grenoble, Gift of Madame Amélie Matisse and Mademoiselle Marguerite Matisse, 1922 © Succession H. Matisse / Photo © Ville de Grenoble/Musée de Grenoble Crédit photographique : Ville de Grenoble/Musée de Grenoble Photographer: Jean-Luc Lacroix

Taking this last statement into consideration, let us focus on Matisse’s 1911 Interior with Aubergines, the star of the show and rarely on loan from the Musée de Grenoble, in terms of its spare depictions and the artist’s self-referential iconographic codes, such as the little nude sculptures, the open window, and the lively textile prints – all signature motifs since Matisse’s first Fauve work Open Window, Colliour, 1904 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Interior with Aubergines (“eggplants” for us Yanks) was completed in the fall before Matisse’s 42nd birthday. Placed in the fourth gallery, “A Deep Dive into Resemblance, 1910-1917,” this giant canvas of nearly 7 x 9 feet deploys a complex organization of space, attempting to fuse the literal and depicted within the duality of art and our lived existence. Thus, numerous rectangles direct the eyes to various types of open and closed forms, from left to right: the fireplace, the mirror, the doorway, the curtain beyond, the screen, the swatch of floral cloth tacked onto the screen, the door, the frame, the shutter, and the open window (yet again).

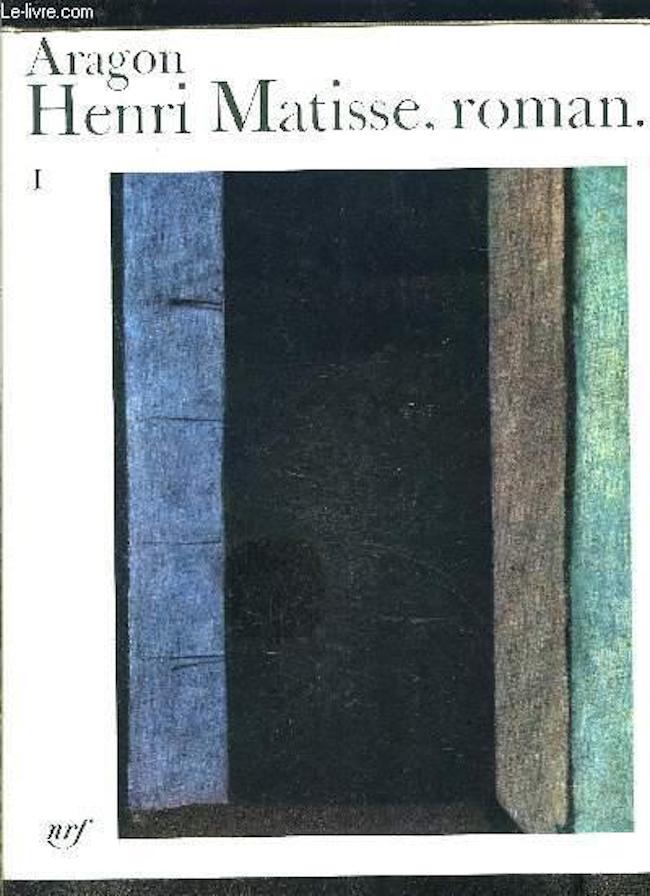

Henri Matisse, French Window in Collioure, 1914, oil on canvas, 116.5 x 89 cm., ©Succession H. Matisse, on the cover of Louis Aragon, Henri Matisse, roman, volume I, Gallimard, 1971

This period (1910-1917) forced Matisse to face the onslaught of Cubist inventions staking their claim in the private galleries and public salons. By the time Matisse finished the ominous black and green French Window in Collioure, 1914, the almost abstract purity of his compositions seem to have permanently shifted from his exuberant lyricism into Le Corbusier’s Purist austerity, well in advance of the Purist movement (1918-1925).

Gone were the humans, as if erased from consideration, and yet, quite present in terms of ourselves. We, the viewers, stand in front of the painting, assuming the artist’s own perspective, and contemplating the mysterious darkness, perhaps an abyss, beyond the picture plane. At this point in his career, Matisse seemed finished with his signature voluptuous female figures, his joyous Orientalized arabesques, and his pulsating tones that became the light source in his art. Matisse would not give up on this rather arid Cubist direction until 1917, when he reached the final stage of Bathers at a River (Art Institute of Chicago).

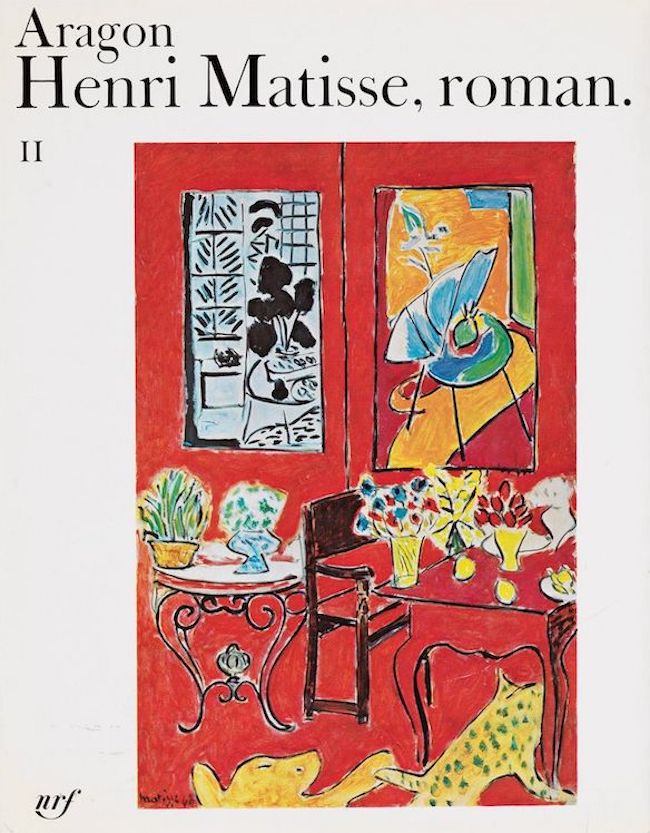

Henri Matisse, Large Red Interior, 1948, Musée National d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou Louis Aragon, Henri Matisse, roman, vol. II, Paris: Gallimard, 1971

Perhaps, the selection of this Cubist work for the cover of Louis Aragon’s Henri Matisse, Roman, volume I, expresses the boundless possibilities and unexplored mysteries of Matisse’s whole oeuvre. Fortunately, this Cubist compromise did not last long. On the deliciously red cover of Henri Matisse, Roman, volume II, we see the return to a joie de vivre (the title of his best known work in the Barnes Collection, now in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, painted in 1905-1906). This genuine zest for life fills the final galleries, especially the last two, “Day of Color” and “The Giant Image,” wherein we relish the extraordinary vitality of his late-career paper cuts.

Most Matisse scholar bristle when Matisse’s 1908 “comfy armchair” remark invades the conversation. Matisse himself regretted the phrase published in a well-known magazine. For the avant-garde phalanx, the bromide sentiment sounded too sappy to identify with, and even believe Matisse said it himself. Numerous subsequent interviews would push this early-career comment into the background, but it was never forgotten. Today it sounds just right. We do need soothing art right now, as familiar and comfy as an old armchair.

Hopefully, Matisse, Like a Novel, will reopen on the first Thursday of the New Year. If you are lucky enough to be in Paris during that period, please look on the Centre Pompidou website for reservation information. Advance reservations, masks and social distancing will still be enforced.

In the meantime, Henri – we wish you Joyeux Anniversaire on December 31, 2020 and une très bonne année,

Lead photo credit : Matisse Comme un roman exhibition cover

More in art and culture, Matisse