Magnum Photos: The Gold Standard for Photojournalism

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

A photojournalist’s job is to tell a story with pictures, articulating the truth with images captured with a camera. The first person to prove a picture was worth a thousand words was Roger Fenton (1819-1869), who pioneered photojournalism in the field during the Crimean War (1853-1856). He is recognized as the first official war photographer to gather images for the Illustrated London News, visually conveying the horrific effects of military conflict to a mass audience. During the American Civil War, Matthew Brady captured images of camp and battlefield life for Harper’s Weekly. By the early 1920s technological advances allowed social documentary photojournalism to flourish, enabling candid photographs of daily life to be depicted by some of the most formidable talents of the day, such as Jacob Riis, Margaret Bourke-White, and Dorothea Lange.

Between the 1930s to the 1970s photojournalism reached its apex. Technology and public enthusiasm, combined with innovations like light sensitive film, the flash bulb, and the compact 35mm camera, made photography more portable than ever. Photo-driven periodicals such as LIFE magazine employed large staffs of photographers and used the photo essay as a means of telling important stories about contemporary society. It was in Paris, in 1947, that photojournalists Robert Capa, David “Chim” Seymour, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and William Vandivert founded Magnum Photos.

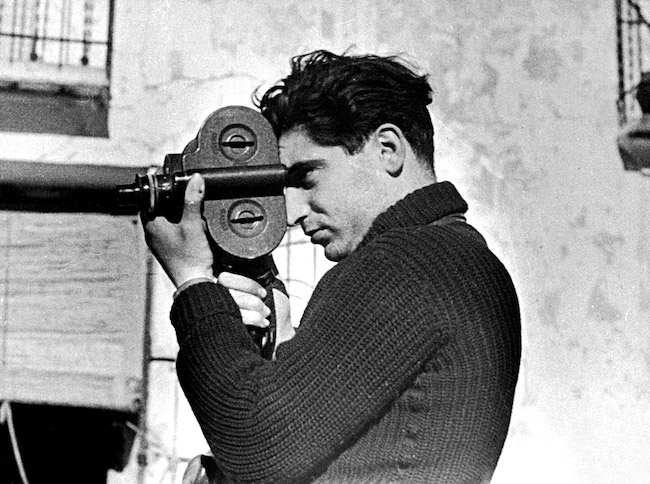

Photographer Robert Capa during the Spanish civil war, May 1937. Captured by Gerda Taro. Photo credit © Wikipedia, public domain

The story of Magnum begins with Robert Capa (1913-1954), born Endre Friedmann on the Pest side of Budapest, Hungary, into a middle-class, Jewish family. At the age of 18, he was forced into exile for his leftist beliefs and settled in Berlin. Forsaking his journalism studies at university, he found work as a darkroom assistant, teaching himself to take photographs with a Leica camera. Capa’s first big assignment was to photograph Leon Trotsky at a lecture in Copenhagen. The Trotsky images were part of a magazine story that earned him his first photo credits. His photographs of the exhausted, troubled-looking Trotsky were stand-outs.

With the rise of Hitler’s Nazi party, Capa was once again forced into exile, moving to Paris in 1933. It was at the café Le Dôme in Montmartre that he met David “Chim” Seymour (born David Szymin), a Polish photographer working for Paris Soir and Regards, who later introduced him to the artist-photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Capa and his partner, Gerda Taro (a Swiss photojournalist who fled Germany the previous year), Chim, and Cartier-Bresson brought their cameras to the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Capa’s “The Falling Soldier” is one of his most iconic photographs and remains an unsurpassed image of war. A Spanish government minister of the 1990s described it as “…a universal icon… on a par with Picasso’s Guernica.”

While Capa traveled back to Paris for work in July 1937, Taro died tragically when the car she was traveling in was crushed by a tank. She is considered the first female photojournalist to die while covering a war. In 1938 Cartier-Bresson traveled to London on assignment for Ce Soir to cover the coronation of King George VI, and in 1939 Chim moved to Mexico on assignment for Paris Match.

View this post on Instagram

After shooting the first war images in color while filming a documentary in China during the second Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945), Capa returned to Spain to cover that country’s takeover by Francisco Franco. While in Spain he met the writers Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, who were both there on assignment. When LIFE magazine published a story about Hemingway’s time in Spain, it included a series of photographs by Capa, labeling him “The Greatest War-Photographer in the World.” Coincidentally, in 2007, a suitcase containing some 4500 negatives of the Spanish Civil War by Capa, Taro, and Chim were discovered in Mexico. Presumed lost since 1939, the images and the story behind this treasure were subsequently made into a documentary film, The Mexican Suitcase, which is available online.

After the Second World War broke out across Europe, Capa left for New York City, taking jobs with LIFE and TIME magazines. Following a brief a stint in Mexico, he returned to England in 1941 to cover the war. Two years later he was sent to the North African front with Allied Forces, and later covered the fighting in Italy, where he met the trailblazing British photojournalist George Rodger. Rodger became the first photographer to enter the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen. Traumatized by what he saw he swore never to take a war picture again.

Capa’s blurred photographs of the D-Day landing at the beaches in Normandy brought the realities of the war to the viewer with an immediacy previously unimaginable. Cartier-Bresson, who was initially embedded in the French Army as a photographer, spent much of the war as a German prisoner. After a daring escape on his third try, he joined the French Resistance. Chim moved to New York and set up a darkroom on 42nd Street. In 1942 he joined the U.S. Air Force and served as an interpreter of reconnaissance photographs for the U.S. military. He later learned both of his parents had been killed in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Magnum Photos was founded two years after the war ended. The initial group was comprised of Capa, Rogers, Chim, Cartier-Bresson, Vandivert and his wife, Rita, and Maria Eisner. By then, all of them were feeling psychologically exhausted and disconnected from reality. “…Back in France, I was completely lost,” Henri Cartier-Bresson explained in an interview in Le Monde. Capa and Rogers in particular were also tired of the ongoing exploitation of freelance photojournalists by large magazines. “Capa recognized the unique qualities that we ourselves had acquired during years of contact with all the emotional excesses that go hand in hand with war,” Rodger said. “He saw a future for us.”

Vandivert had been a photographer for the Chicago Herald Examiner when we was hired by LIFE magazine. For LIFE he photographed the Bengal Famine of 1943 in India, the atrocities at the Gardelegen concentration camp, the Berlin ruins and Aldolph Hitler’s bunker. For a short time Vandivert, his wife Rita, and Maria Eisner, were part of the original Magnum team, but left soon after. A photojournalist herself, Eisner fled Germany in 1933. She started the Alliance Agency in Paris representing photographers. It was she who sent Capa and Chim to cover the Spanish Civil War in 1936. By June 1940 she was regarded as a German alien and sent to a little-known refugee camp at Gurs in the Pyrenees. She later fled to Portugal and settled in the United States.

View this post on Instagram

Although it has been rumored that the name “Magnum” was chosen because the founding members always drank a magnum of champagne at their meetings, it was also indicative of the enterprising boldness of its founders. Magnum’s first decision was to divide the world into areas of coverage, with Chim in Europe, Cartier-Bresson in India and the Far East, Rodger in Africa, and Capa to roam at large. They had some early success, such as Capa’s uncensored look at the Soviet Union behind the Iron Curtain in collaboration with writer John Steinbeck, and Cartier-Bresson’s landmark coverage of India at the time of Gandhi’s assassination. Chim photographed the children of Europe for UNICEF, while Capa documented the Israeli War of Independence (1947-1949), and the founding of the state of Israel. Cartier-Bresson captured a classic portrait of Gandhi one hour before he was assassinated, and Rodger produced an amazing account of the never-before photographed Nuba tribe, which first appeared in National Geographic in 1951.

Initially based in Paris and New York (followed by offices in London and Tokyo), Magnum was the first co-operative, freelance photography agency. In the spirit of cooperation, they dedicated themselves to focus on world events: the bad and the beautiful. Negatives and copyrights would be owned by the photographers, not by the magazines that published their work. None of the founders wanted to suffer the dictates of a magazine’s editorial staff any longer. They wanted the flexibility to choose their own stories, believing photographers had a unique point of view in their imagery that transcended any conventional reporting of contemporary events. “In the words of Cartier-Bresson, “There’s no standard way of approaching a story. We have to evoke a situation, a truth. This is the poetry of life’s reality.”

View this post on Instagram

Magnum continued to add to its roster talented young photographers such as Eve Arnold, Cornell Capa (Robert’s younger brother), Elliott Erwitt, and Inge Morath, among many others. For a list of all the Magnum photographers and their stories, visit: magnumphotos.com/photographers. Tragically, Capa died in 1954 while covering the French war in Indo-China, when a landmine exploded as he photographed soldiers advancing through a field. He was only 40-years-old. Chim was killed by Egyptian machine-gun fire in 1956, while traveling near the Suez Canal to cover a prisoner exchange. He was 45.

Cartier-Bresson continued to travel the world, taking photographs, writing, and helping to establish photojournalism as an art form. His beautifully composed images were products of an incomparable eye, capturing moments so remarkable you can hardly believe they were not staged. He left Magnum in 1966. After photographing the 1968 student revolt in Paris, he turned to making motion pictures—including Impressions of California (1969) and Southern Exposures (1971). Cartier-Bresson devoted his later years to drawing. He died at the age of 96 in 2004.

View this post on Instagram

Over the next 30 years Rodger worked as a freelance photographer, completing numerous expeditions and missions to photograph the people, landscapes and natural wonders of Africa. Enormously successful during his lifetime, much of his photojournalistic work in Africa was published in art books and in National Geographic.

When LIFE magazine closed in 1972, the golden age of photojournalism ended. Consequently, Magnum photographers sought new ways of depicting their contemporary world. For some, this meant traveling to photograph cultures untouched by technology, while for others it meant looking at subcultures that had previously been overlooked. They moved away from the traditional black and white photograph into a vibrantly colored world that continues to astonish. Today, to quote the official website, “Magnum represents some of the world’s most renowned photographers, maintaining its founding ideals and idiosyncratic mix of journalism, art and storytelling.” Ninety-eight photographers currently make up the Magnum cooperative. Offerings include educational programs, workshops and seminars, portfolio reviews, mentorships and online learning.

Thousands of men and women have sought to convey the human condition through a lens, but the original Magnum photographers created the gold standard for photojournalism.

View this post on Instagram

Lead photo credit : A picture of refugees taken by Capa. Robert Capa - International Center of Photography / MAGNUM. Photo credit © Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

More in Magnum Photos, photojournalism

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY