Aïcha Goblet: La Vénus de Montparnasse in the Roaring Twenties

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“Montparnasse is Aïcha. Aïcha almost alone, since the death of Libion, the original owner of La Rotonde. Everyone knows her.” So begins Emmanuel Bourcier’s article “La Vénus de Montparnasse,” in Paris-Soir, (April 17, 1931) under the rubric “Aicha la Vedette.” Aïcha the Star. And indeed she was, shining brightly well before Josephine Baker débuted in La Revue Nègre on October 2, 1925 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, fresh off the boat from New York. When Josephine Baker — the sixth woman, first American and first woman of color inducted into the Panthéon — eclipsed Aïcha as the toast of Paris, the world slowly forgot their Montparnasse “princess.”

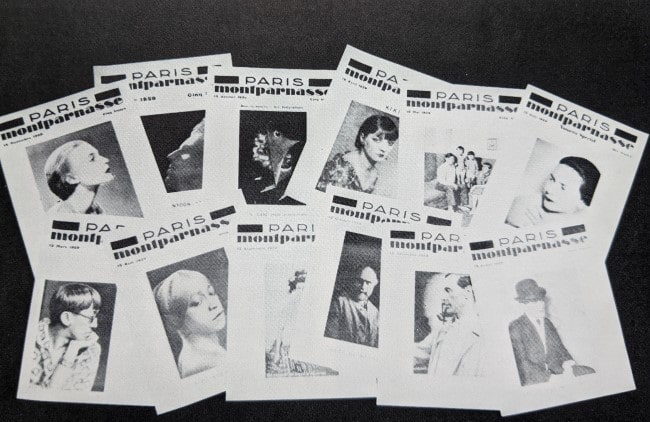

Aïcha on the cover of “Paris-Montparnasse”, August 15, 1929.

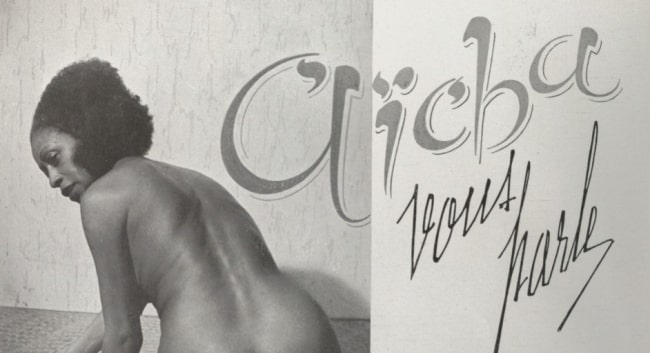

It was the journalist Henri Broca who crowned Aïcha in the August 15, 1929 issue of Paris-Montparnasse. The article “La Princesse Aïcha et le Mage Pascin” praised this in-demand model, dancer, and actress, who was born in 1898 in the northern French mining town of Hazebrouck. Her Belgian mother and Martinique-born father had nine other children. “Take note, I am Flemish,” she wrote in her autobiographical article “Aïcha Speakers to You,” published in Mon Paris (June 1936). “I am the only Black in my family. When I write my true Memoires, as someone has asked me to do, I’ll explain this discreetly.” Oh, Aïcha had her secrets, which, unfortunately, she took to the grave.

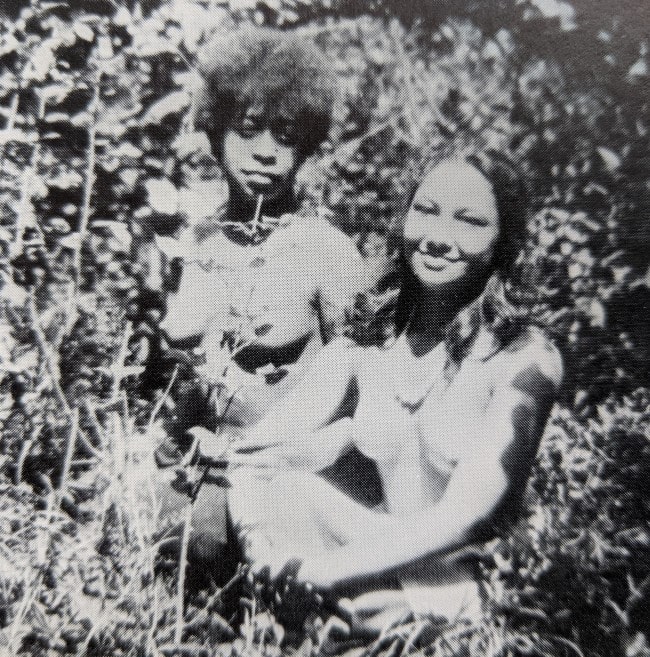

A still from the 1926 film recording of the Bal de la Horde, organized annually by the artists of Montparnasse at the Bal Bullier, wherein artists, actors, cabaret performers, and the general public rubbed shoulders in formal dress or costumes. Here we see Aïcha dancing with another Jules Pascin model Julie Luce, wearing only two necklaces and a grass skirt. Well before the international American star Josephine Baker arrived in France, Aïcha invented a theatrical Afro-Caribbean stereotype for these costume balls and on stage that featured very little corporeal coverage.

Aïcha with Simone Luce in Fontenay-aux-Roses, n.d. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930′ (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

Unfortunately, much that is written about this beloved member of the avant-garde offers sound facts and some mistakes, including the Aïcha Goblet biography written in the catalogue for the 2019 exhibition Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse at the Musée d’Orsay. Like most sources, this entry claims that Aïcha Goblet “inspired” André Salmon’s 1920 novel La Négresse du Sacré Coeur (Black Venus in translation). That’s not true. Salmon’s story takes place in 1907. Aïcha was only nine years old and not living in Montmartre with Picasso and his gang, who were the inspiration for Salmon’s characters. As Salmon explains in his author’s notes, written around August 1953 and published in the 2009 edition, the main character Cora was based on people who lived in this neighborhood at that time. “The model and dancer Cora, whose Christian name I forgot, lived in some part of the Butte that she would traverse with her gentle gait.” (Gallimard, 2009, p. 277). I am indebted to Dr. Jacqueline Gojard, Professor of Literature, University of Paris III (Sorbonne Nouvelle), who edited and wrote the introduction to the 2009 edition of Salmon’s novel, for her confirmation that Aïcha was not the source for Cora.

Aïcha at the Watteau Ball, top left just below André Salmon. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

Aïcha grew up on the fringe of mainstream society. At six, she joined a traveling circus and knew only a peripatetic life until the age of 16, when the French-Bulgarian artist Jules Pascin (originally Julius Mordechai Pincas, 1885-1930) “discovered” her. It was just before the outbreak of World War I in 1914. “Dear Pascin, our wonderful painter of nudes and intimacy that is so touching in its daring, saw me by chance, all black on my white horse, and he changed the direction of my life. Oh! It wasn’t an abduction. Pascin has his lordly fantasies. I respected him like a brother, and I respected him because of his genius. I am not saying this to defend my virtue. I am not a hypocrite… I am just telling the truth.”

Jules Pascin, André Salmon, Jeanne Salmon, Aïcha, Kiki, Simone Luce, and others, in Chelles. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

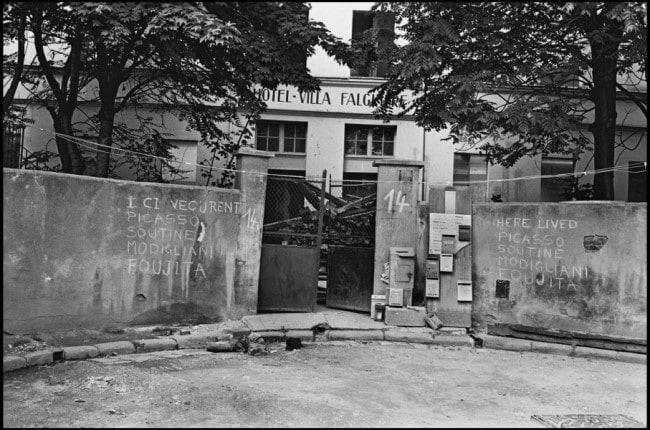

Pascin was “excessively jealous of his friends,” Henri Broca learned from Aïcha during their tête-à-tête in her modest apartment located in the Villa Falguière, in the Cité Falguière. “I never posed for him in the nude. He had as much respect for me as friendship.” And she recounted his warnings not to speak to this guy or that guy because of their bad reputations. “When I arrived in Montparnasse to meet Pascin,” she told Emmanuel Bourcier, “Black people weren’t yet in vogue. I posed for everyone, and I became a star among the painters.” Aïcha did not exaggerate. In 1931, Bourcier wrote: “Everyone knows her gazelle-like eyes, her sparkling smile… her glass necklace, her enormous opal ring, her anecdotes, her taste, her body, and her life. Any artists who would like to become well-known… carry within their hearts her image and her laugh that rings out as far as Yeddo, Philadelphia, Moscow and beyond.”

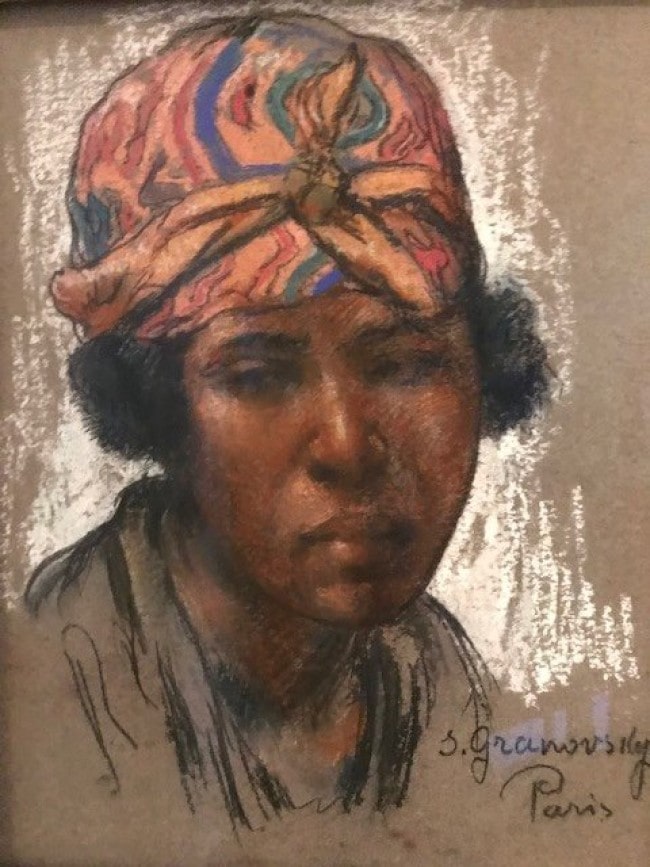

Samuel Granowsky, Portrait of Aïcha, n.d. © Samuel Granowsky

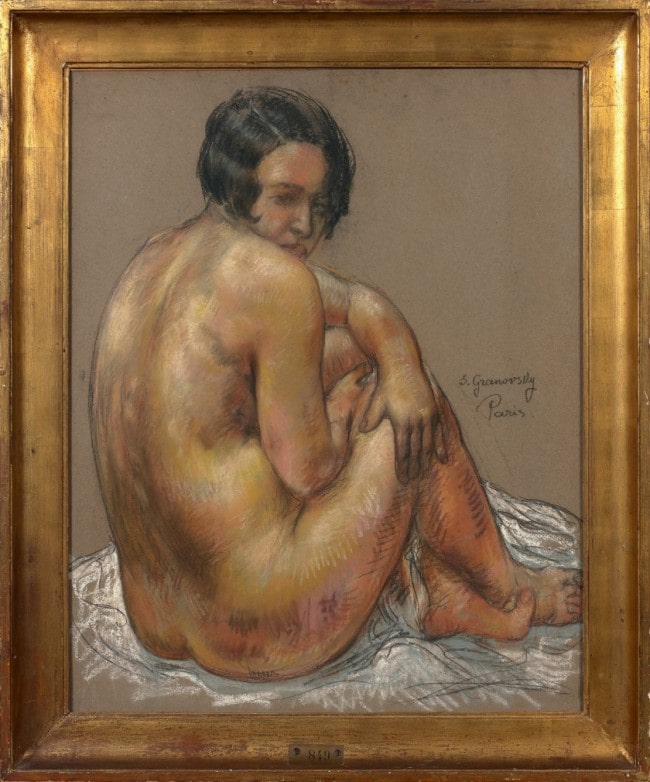

Aïcha eventually freed herself from Pascin’s controlling grip about one year after he took her under his wing, sometime in 1915 or 1916. Most of the artists she posed for belonged to Pascin’s circle, members of what the critics called the École de Paris (immigrant artists who settled in Paris): Kees van Dongen, Amedeo Modigliani, Moïse Kisling, Tsugouharu Foujita, Man Ray, and her companion Samuel Granowsky, the “Cowboy of Montparnasse,” among so many others. She also posed for Matisse in 1917 with his favorite model at the time, Lorette.

Samuel Granowsky, Nude [Aïcha], n.d. © Samuel Granowsky

Two years into the Great Depression, the sense that Montparnasse’s golden years were fading seeped into Aïcha’s recollections for Emmanuel Boursier. She remembered earning more as a model (600 francs per month) than some artists received for their art back in the day (late 1910s to early 1920s). Then, out of the kindness of her heart, she would cook meals and invite these impecunious fellows who also lived in the Villa Falguière, such as Modigliani, Soutine, Foujita, etc.

“What a happy time that was! Life was so sweet! You could buy a pouch of tobacco for two sous, stuff it in your pipe and make art, with the leisure to think, reflect and discuss. Models were paid one hundred sous, three francs, and even nothing. We would lunch together, and when the session was done, we went to the theatre,” Aïcha reminisced. “In the olden days, it took three or four months to finish a painting. They were pompier (academic), perhaps, but it was serious and skilled.” A good example of this meticulous pompier brushstroke appears in Félix Vallotton’s Portrait of Aïcha, reproduced above.

Hotel-Villa Falguière in 1967, photographed by Daniel Angeli. © Daniel Angeli

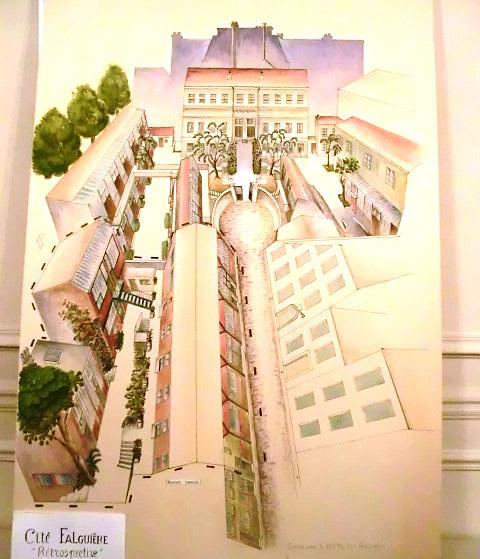

Cité Falguière, illustrated by Jacques Mauve, ca. 1910

In the 1920s and 1930s, Aïcha also acted on stage. Most notably, she participated in Gaston Baty’s productions for his own company Les Compagnons de la Chimère (Companions of the Chimera). In 1921, she played Nyota in Haya by Herman Grégoire, Comédie des Champs-Élysée, and in either 1921 or 1931, she had a part in Le Simoun (Desert Wind) by Henri-René Lenormand. In 1924, she had a role in À l’Ombre du Mal (In the Shadow of Evil), another play by Henri-René Lenormand, and in 1935, she was cast in Hôtel des masques by Albert-Jean. In 1925, she took the stage in La Cavalière Elsa by Charles Demasy, based on a novel by Pierre Mac Orlan, in which she danced in a Bolshevik costume to play Prince Hamlet.

“I was almost nude,” she recalled in Mon Paris. “They gave me a little belt, preparing France for the arrival of the illustrious Josephine [Baker], who still wasn’t here. Nothing hid my stomach and thighs.”

André Salmon, Aïcha, Hermine David, and Pascin’s hand, cropped, at an outdoor café in Saint Meurice. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

While Aïcha’s fame evidently reached the contemporary press, more personal anecdotes can be found in letters written by the friends who greatly appreciated her kindness, intelligence, and feeling for art. In Kiki [Alice Prin]’s Memoirs (1929), the infamous model and toast of Montparnasse remembered the throng of activity among the regulars in the neighborhood. While the art students from the various academies were toting their canvases here and there, the models sat at Le Select or Le Dôme. “There were few nicer than Aïcha, Bouboule and Clara.”

We also know from Broca’s August 1929 article in Paris-Montparnasse and in Pascin’s letters written during the summer of 1929 that Aïcha hosted a party on October 2nd, which had the distinction of inaugurating the social season after the rentrée. Worried this time of year might result in a small turnout for his dear friend, Pascin wrote to his paramour Lucy Krohg about his concerns. His fears proved to be unfounded. The triumph of Aïcha’s fête remains on record in the October 15th issue of Paris-Montparnasse: “Surrounded by friends and flowers, Aïcha presided over the dinner with her lovely gracefulness, knowing how to maintain her famous smile from beginning to end. Thanks to her, it was one of our most successful meals.”

Hermine David, André Salmon, Aïcha, and others in Chelles. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

André Salmon certainly attended this dinner in honor of Aïcha, one of his closest friends. We see him sit or stand next to her in numerous photos taken at parties and on vacation. Described in his memoir Montparnasse (1950), Salmon characterizes a moment with Aïcha sitting at Le Dôme: “Aïcha introduced herself to painters by taking out of her little purse her cute visiting card with its touching bit of poetic marketing, a little bouquet of flowers illustrated on the top left corner. There we read: Aïcha Goblet, artiste. Actress? Aïcha wasn’t lying… Aïcha knew how to hold forth [here] as well as in the studio in front of a painting made possible by the agreeable nature of a nude model.”

Aïcha Goblet, “Aïcha Speaks to You”, © Mon-Paris, June 1936 (number 8), page 7.

Aicha returned the compliment in her 1936 Mon Paris memoir: “Along with painters, I knew poets. I call André Salmon simply ‘André.’ And it was he who asked me to compose this brief essay of recollections.”

Lucky indeed are we that Salmon, Broca, Bourcier, Kiki, and a few others preserved their impressions of Aïcha. Unfortunately, little is known about Aïsha after this flurry of attention during the 1920s and 1930s. We believe that she remained in a relationship with the artist Samuel Granowsky, but never married. Granowsky, a Jew born in the Ukraine in 1882, was arrested by the Nazis on July 17, 1942, brought to the detention camp Drancy, and sent to Auschwitz on July 22nd, where he was executed. From that point on, we have little to no information about Aïcha Goblet’s final years. Perhaps she remained in Paris. More research must be done to trace her life after the Great Depression. We do not know when she died or where she is buried.

Another neglected fact about Aïcha, recorded in her Mon Paris memoirs, was her art practice, pursued under the mentorship of the American dancer and artist Raymond Duncan (1875-1966), brother of the modern dance icon Isadora Duncan (1877-1927). The Duncans cultivated their reverence for Greece and developed a particular method of dance inspired by ancient Greek movement. Duncan and his Greek wife Penelope started a school in Paris in 1911 called the Akademia Raymond Duncan, which eventually found its permanent home on the rue de Seine. The Akademia offered free training in dance, art, and craft. The Duncans also produced theatrical performances. We know nothing about Aïcha’s artistic creations or if any survived.

Aïcha holding court at Le Dôme with Hermine David, Pascin’s wife, and other friends. © Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

Nevertheless, this aspect of Aïcha’s range in avant-garde circles surely influenced her taste which she shared with her colleagues and friends. Never as internationally famous as the American Josephine Baker, Aïcha honed a Parisian persona that reflected the best of her close-knit Montparnasse clique. With this faint notion of what Aïcha meant to her contemporaries, it seems unconscionable to let her legacy fade. We must instead heed Henri Broca’s closing remarks in his Paris-Montparnasse article about this cherished friend: “I left Aïcha with the sincerest hope that she didn’t think we could abandon her. Maybe life’s obligations lead to some desertions among some friends. But no one forgets Aicha. We cannot forget her because she perfectly embodies the abundant sweetness of Montparnassian mores. And because she is, more than so many others, a small living rock upon which rests this huge active construct that is Montparnasse. May Aïcha know that at this magazine she has only friends, and may she feel assured that here we only pursue one goal: ‘expressing respect for those to whom Montparnasse owes something’.”

At this moment, Broca’s hopes have not been fulfilled. We have forgotten Aïcha and her Montparnasse charm. We have forgotten that she was a celebrity among her peers and in the press. I am writing this article with the hope that more extensive research and accurate publications will rescue Aïcha from oblivion.

Aïcha in Montparnasse, a cropped photo published in Billy Klüver and Julie Martin’s “Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers, 1900-1930” (Harry N. Abrams, 1989)

Lead photo credit : Félix Vallotton, Aïcha, 1922. Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm. © Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Public Domain

More in French history, french women, history, women in history

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY