How Many Women are Honored in the Panthéon?

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Presumably no-one disputes that women can be national heroes. But when it comes to the supreme honor of burial in the Panthéon in Paris, the inscription spelt out in large letters on the building’s façade casts a doubt. It reads Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante, meaning “A grateful nation honors its great men.” This topic is newly relevant, given President Emmanuel Macron’s recent announcement that Josephine Baker is to be inducted into the Panthéon in November. Of the 80 people thus honored, she will be only the sixth woman and the first Black woman, making this a good moment to look back over the history of women in the Panthéon and trace their story.

Joséphine Baker en 1940, photographie Studio Harcourt. (C) Studio Harcourt, Public Domain

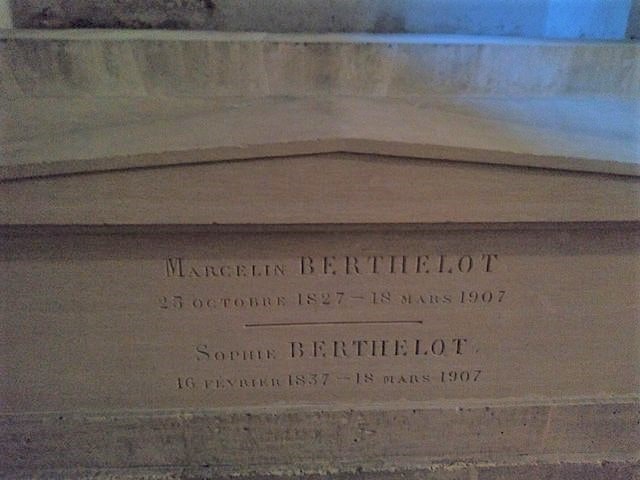

The very first ceremony, for the writer Voltaire, took place in 1791, but it was not until 1907 that a woman was buried there and the reason for her inclusion was certainly no victory for feminism. Sophie Berthelot was there simply because her husband, Marcellin Berthelot, a world-renowned chemist, had specifically requested that his wife should remain beside him even in death. It was decided to do as he wished “in homage,” as it was put at the time, “to her conjugal virtue.” Afterwards she was described as L’inconnue du Panthéon, the “stranger in the Panthéon,” a lone woman among all those eminent male politicians and scientists and one not there in her own right.

Tomb of Marcellin and Sophie Berthelot in the Panthéon (C) Lucas Werkmeister, (CC BY 4.0)

It was certainly progress when the remains of Marie Curie, the pioneering physicist, were moved to the Panthéon from her original burial place in a cemetery at Sceaux. In 1995, 60 years after her death, her remains and those of her husband Pierre were transferred to the Panthéon in honor of their ground-breaking work in the field of radiation. Marie Curie had been the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, in fact she was the first person to win two, and so her achievements were beyond question. However, it was another 20 years until another woman was recognized in the same way.

Marie Curie. (C) Henri Manuel, Public Domain

In 2015, President François Hollande moved things forward a little. Two more women were honored, for the bravery they showed as members of the Résistance during World War Two, but also for their courageous moral stand in the after-war years. Highly respected for who they were, perhaps they also represented all the other women who played their part in standing up to the Nazi regime during the Occupation. This national recognition that courage and serving one’s country are not solely the province of the male sex can be seen as a step towards equality!

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz (C) Nelson Minar, (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz was an active member of the Résistance from 1940 until her arrest in 1943 and subsequent deportation to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. After the war she became a member – and eventually president of – the ADIR*, fighting for the rights of former prisoners and those who had been deported, filing lawsuits against Nazi war criminals, for example. And in 1988 she turned her attention to a very different social problem, joining the French Economic and Social Council in their fight against poverty and, after 10 years of campaigning, finally seeing her “law against poverty” enacted. Geneviève’s Panthéon ceremony was “symbolic,” that is she remains buried next to her husband in Bossey, Haute Savoie, as she had wished, but soil from her grave was transferred to the Panthéon.

French resistance in 1944 (C) Donald I. Grant,, Public Domain

Also honored in 2015, Germaine Tillion was a Résistante who had helped prisoners flee, even giving one Jewish family her own family papers so they could escape persecution. Betrayed and sent to Ravensbrück, she too survived and took up other causes after the war, notably opposition to the use of torture by French forces in Algeria and, much later, to torture in Iraq. She worked tirelessly too in defense of the rights of immigrant women in France. By the time of her death at the age of 100 she was one of only five women who had been awarded the Grand Croix of the Légion d’Honneur.

Simone Veil (C) Rob Croes, (CC0 1.0), Public Domain

In 2018 President Emmanuel Macron chose Simone Veil as the fifth woman to be interred in the Panthéon. Jewish, and a Holocaust survivor, Simone Veil became a politician and as health minister she campaigned to legalize contraception and abortion in France, despite strong opposition. She later served as president of the European Parliament and continued to support feminism and to fight anti-semitism. Elected a member of the prestigious Académie Française, she had both her Auschwitz tattoo number and the French motto – Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité – engraved on her ceremonial sword. A public petition called for her burial in the Panthéon, showing French society’s strong support of equality. And, in a reversal of what happened with Sophie Berthelot, Simone Veil’s husband was buried alongside her, following their request to remain together.

Baker in uniform in 1948 (C) Studio Harcourt, Public Domain

The recent decision to honor Josephine Baker moves things one step further because, as a Black woman, she is another “first.” She is remembered by the public above all for her roaring success on stage in Paris in the 1920s, performing provocative dance routines to adoring audiences. But it is for her courageous loyalty to France, her adopted country, as a resistance fighter that she is to be honored. When recruited to the Resistance, she said: “The Parisians gave me their hearts, I am ready to give them my life.” No less significant are her moral courage in defense of civil rights in the U.S. and her ongoing campaigns against racism worldwide after the war.

There has been some controversy. Some remark cynically that the choice of a Black woman suits President Macron’s desire to gain wider appeal before next year’s election. But the writer Laurent Kupferman has spoken powerfully about why Josephine Baker fully deserves the honor, saying: “She should not be inducted into the Panthéon because she was a woman or because she was Black … she should be inducted because of the acts of courage she performed for this country.” That surely sets the standard, while also giving us confidence that in future the list of those chosen to receive France’s highest honor will become more inclusive.

** ADIR Association National des Anciennes Déportées et Internées de la Résistance

Lead photo credit : The Panthéon in 1795. The facade windows were bricked up to make the interior darker and more solemn. (C) Jean-Baptiste Hilair, Public Domain

More in architecture, Building, France, history, Paris, Woman