The Heroic Parisiennes of the Second World War

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Of all the narratives of France during the Second World War, the accounts of the Resistance and those who collaborated with the hated Nazis still remain the most vivid.

The most famous member of the Resistance, Jean Moulin rightly has a dedicated museum in Paris, celebrating the lauded hero of the Maquis and the various branches of the underground movements of men who daily risked their lives, and often lost them, for a free France.

The Resistance has become mythical. Their names will always be remembered, commemorated, and revered.

And then, on the other side of the coin, there’s another infamous narrative about les horizontales, the women who slept with the enemy, or were seen to have associated with them, sometimes for an easy life, more often simply for basic necessities for their families. After the war, these women were paraded through the streets, hair shorn, branded, reviled by the crowds as almost sub human, treated far more harshly than their male counterparts, who by doing nothing for the cause, or working under the occupier, were no less culpable, but nonetheless did not suffer the same barbaric, public humiliations.

Jean Moulin in 1937. © Wiki commons

But what about the other, lesser known narratives? French women during the war cannot simply be put in two categories: those who stoically got through the daily hardships and deprivations without any aid from the Germans, and those who chose an easier road by collaborating with the enemy.

There was a whole sub-category of women — who quietly, audaciously, and without thought for their own safety — were just as brave, and were meted out the same punishments and retributions from the occupying force as their male counterparts in the Resistance. Because they weren’t armed as male members of the Resistance, these women almost invariably did not receive the same immediate recognition after the war. These same women, who until the outbreak of war in 1939 had been politically invisible, did not have the right to vote and still needed permission from their father or their husband to work or own property, these were the same women who made what could be the fatal choice, of hiding Jewish children or Allied airman, carrying false papers, or spying on the Germans and their troop movements.

These women were many and varied: from vicomtesses, actresses, milliners and even a volunteer assistant curator at the Jeu de Paume museum. Some were foreign born, parachuting into France because of their wireless expertise and their knowledge of the French language. All of them showed immense courage. All of them believed in the cause to free France. Many of them were caught and tortured, imprisoned in camps far from the country they were fighting for.

Many of them died. Here is the story of just three of them.

Signs showing the way to German headquarters of Greater Paris, 1940 © Wiki commons

Jeannie Rousseau. (Jeannie Yvonne Ghislaine Rousseau.) Born: April 1st, 1919 in Saint-Brieuc.

Rousseau was the daughter of Jean Rousseau, a World War I veteran and French foreign ministry official. She graduated from Sciences Po in 1939, acknowledged as a brilliant linguist.

In 1940, her father moved the family to Dinard on the Brittany coast, since he believed Paris to be too dangerous and thought the war would not reach that part of France. But then with the imminent prospect of an English invasion, the German army soon flooded the area. Jeannie, fluent in German, began to work as a liaison officer between the local mayor and the German army. Like most French citizens, at the beginning of the war, Jeannie had found the Germans affable, eager to please, and wanting to be liked. She was young and pretty, and the Germans were careless about talking in front of her. Approached by a Resister, Jeannie was more than able to supply details of specific names and numbers of German operations in the Dinard area that were then passed on to the British.

Jeannie Rousseau

It was obvious to the Gestapo that there was an agent in the area and Jeannie was arrested in 1941 and held in Rennes prison for a month. She was 22 years old. When the German tribunal examined the case against her, the Wehrmacht officers from Dinard, unable to believe that sweet Jeannie could be a spy, defended her, and she was released. Suspicion lingered however, and she was ordered to leave the area.

Jeannie went to Paris, unperturbed by her arrest, and with espionage now firmly running through her veins, took a job as an interpreter for a French Industrialist syndicate dealing with selling strategic goods to the Germans. But her knowledge and photographic memory were of little use unless she could pass it on to the appropriate quarters. That person came in the guise of Georges Lamarque, who had met Jeannie on a train to Vichy and remembered her brilliance from Sciences Po. Lamarque recognized the importance of the information Jeannie was privy to every day. Jeannie immediately agreed to work for Lamarque, and some of the reports she filed about German missile and rocket development were simply astonishing in their detail and importance, and of priceless value to the allies.

Jeannie Rousseau

Just before D-Day, an attempt to evacuate Jeannie with two other agents was foiled by the Gestapo and she was captured. Three concentration camps, the dreaded Ravensbrück, Konigsberg and Torgau, did not break Rousseau. She was rescued by the Swedish Red Cross shortly before the end of the war, severely malnourished and suffering from tuberculosis.

Rousseau died in Montaigu, Vendée, aged 98. She had been awarded the Legion of Honor in 1955 and Resistance Medal and Croix de Guerre. Amazingly Rousseau’s story remained largely unknown until 1993. She had avoided interviews with reporters and historians until she accepted the Central Agency’s Agency Seal.

The reason for her reticence in telling her story was that she said that other women had done more.

Jeannie Rousseau (de Clarens) with James Woolsey and Reginald Victor Jones in 1992. Public domain.

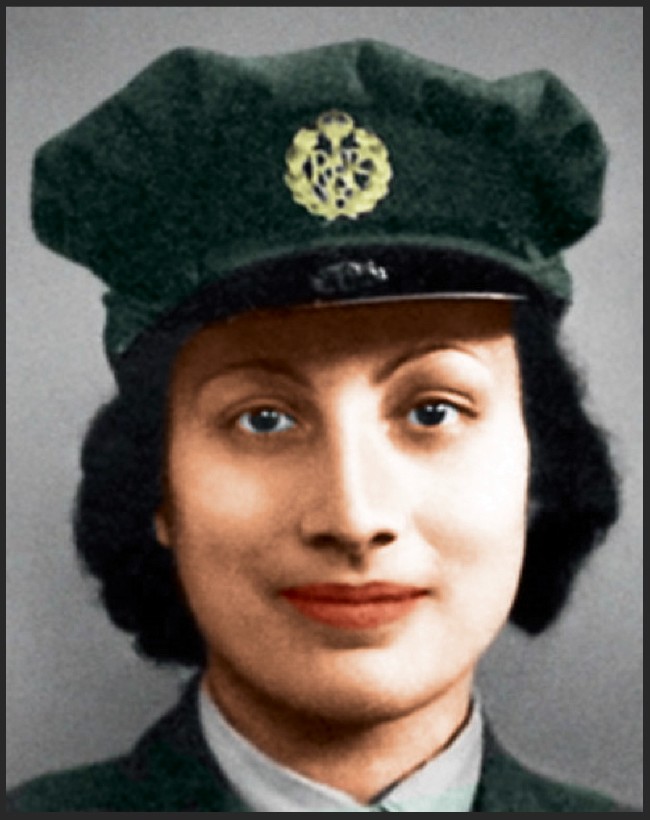

Nora Baker. (Noor Inayat-Khan.) Born: January 1st, 1914 in Moscow.

Noor Inayat-Khan was perhaps one of the most atypical of spies, her bravery shockingly underestimated. The part-American daughter of an Indian sufi mystic, Inayat khan, who lived in Europe as a music teacher, and her mother Ora Ray Baker (Pirani Ameena Begum) from Alburquerque, New Mexico, the family left Russia in 1914 and moved to Bloomsbury in London before moving to France, near Paris in 1920.

Noor was a dreamy, sensitive girl, who went on to study child psychology at the Sorbonne and music at the Paris Conservatory. By the beginning of the war, Noor was publishing poetry and children’s books. After the German invasion, the family fled once more, back to England, where her story should have ended. Despite Noor holding strong pacifist ideals, both she and her brother wanted to contribute somehow to help defeat Nazi tyranny.

The Paris Opera decorated with swastikas for a festival of German music, 1941. Public Domain

Calling herself Nora, and giving her religion as Church of England, Noor joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and was sent for training to be a wireless operator. She was assigned to bomber training school in June 1941. Because of Noor’s linguistic abilities, she came to the attention of SOE (Special Operations Executive) and was selected for special training as a wireless operator in occupied territory. Up until that time, women had only been sent overseas as couriers.

The course included finding safe places in an unknown environment to transmit messages back to their instructors and making sure they weren’t followed by enemy agents. The last of the exercises was a mock Gestapo interrogation, to give the agents an idea of what would be in store for them if they were captured as spies.

Noor Inayat Khan, c.1943. Photo credit: Russeltarr / Wikimedia Commons

Noor’s final assessment was brutal, especially regarding the mock interrogation, where her instructor wrote that, “she was overwhelmed, she nearly lost her voice” and that afterwards, “she was trembling and quite blanched.” Long after the war ended, her finishing report was equally damning, stating amongst other criticisms, that Noor “has an unstable and temperamental personality and it is very doubtful whether she is really suited to work in the field.” Others noted that Noor tended “to give too much information,” and “came here without the foggiest idea what she was being trained for.” There was no let up in her unsuitability for the task ahead with athletic instructors labelling her “clumsy, unsuitable for jumping and pretty scared of weapons…”

All this for the first female SOE officer to be parachuted into France as a wireless operator, one of the riskiest, most dangerous jobs of all. So dangerous indeed, that in 1943, a wireless operator’s life expectancy was six weeks.

After a performance of Schiller’s ‘Intrigue and Love’ at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in 1941. © Wiki commons

Vera Atkins, the intelligence officer for F section, after receiving more news about Noor’s state of mind, had second thoughts about sending her and gave Noor the opportunity to back out gracefully without any recriminations or black marks on her file. Noor refused and insisted she was competent for the work.

Vera Atkins © Public Domain

On the 16th/17th June 1943, Noor, under the cover identity of Jeanne-Marie Regnier, was parachuted from a Lysander plane into northern France, and thence onto Paris. Within days, the network Noor was meant to work with had been betrayed and was in the hands of the Germans. While other agents were ordered to escape via the Pyrennees, Noor was told to lay low in Paris, where soon, despite the obvious dangers, she began transmitting again. Not heeding basic training and desperate to be of help, Noor not only transmitted unencoded messages, but also copied the messages into a notebook. Noor was betrayed, for money, most probably by Renée Garry. Déricourt, an SOE officer and double agent, and on October 13th, 1943, Noor was arrested and interrogated at the SD headquarters at 84, Avenue Foch. Noor attempted an escape on November 25th but was recaptured with another SOE agent John Renshaw Starr and the resistance leader Leon Faye.

Noor divulged no information during her interrogation and after refusing to sign a declaration announcing any future escape attempts (perhaps the only known spy who did not believe in lying), Noor was sent to Germany and imprisoned at Pforzheim. For 10 months, Noor was kept in solitary confinement, her hands and feet shackled, and in chains most of the time. The prison director after the war testified that throughout the entire time of Noor’s appalling confinement, she had remained uncooperative, refusing to divulge any information either of her work or her fellow operatives.

On September 12th, 1944, Noor was transferred to Dachau Concentration Camp with fellow agents Eliane Plewman, Yolande Beekman and Madeleine Damerment. The following morning, at dawn, all four women were executed

Eliane Plewman © Public Domain

This dreamy writer of poetry, musician and devout Muslim, barely thirty years old, had confounded all those who had doubted her courage under duress.

Noor Inayat Khan, was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1949 and Croix de Guerre with silver cross.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz. Born October 25th, 1920

The niece of General de Gaulle, Geneviève, a young girl of 20, was inspired to join the resistance after listening to Marshall Petain’s “cowardly surrender” in June 1940. Her father (De Gaulle’s elder brother) had already made her read Hitler’s Mein Kampf and incensed by Hitler’s doctrine and the invasion of her country by the Nazis, she impetuously pulled down a Nazi flag flying from a bridge over the river Vilaine in Brittany.

Motherless from the age of four, Geneviève wanted to emulate her brother Roger who had already crossed the border into Spain and joined the Free French Forces. She returned to Paris and under the pseudonym Galliard, wrote articles for La Defence de la France. Not content with using words, Geneviève began to help people to escape either to Spain, (often accompanying them to the border) or Brittany. Like many women in the clandestine life of the Resistance, Geneviève delivered packages and false documents and was always on the look out for useful information. She took advantage of looking much younger than she was, a German official once offering to carry her suitcase which just happened to be filled with arms.

House in Rennes with a Gaulle-Anthonioz plaque. © Wiki commons

Her luck finally ran out on July, 20th 1943 when she was arrested by Pierre Bonny of the French Gestapo in a bookshop in Rue Bonaparte. Scores of members of resistance groups were arrested at that time, many young women like Geneviève. Those that escaped arrest continued their work, but the fear everywhere and especially in Paris was tangible. Nowhere was safe.

Geneviève was first imprisoned in Fresnes before being deported in February 1944 to Ravensbruck concentration camp. Geneviève was placed in isolation in the camp bunker, and was probably spared a death sentence by Heinrich Himmler, who thought she could possibly be used as an exchange prisoner, the value being in her name. She was released in April 1945.

Geneviève did not go quietly back into civilian life, did not try to erase the memories of the war, but instead tried to remedy the injustices. She became president of the ADIR (Association of Deportees and Internees of the Resistance), filed lawsuits against Nazi war criminals, and took part in the rise of her uncle’s political movement, Rassemblement du Peuple Francais. From a permanent volunteer to the movement ATD Quart Monde in 1964, she then became president. In 1987, Geneviève testified in the case of Klaus Barbie and in the following year she became a member of the French Economic and Social Council fighting against poverty.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz painted outside a paper shop on la rue de Tourtille and the la rue Ramponeau in Paris. © Wiki commons

She died on February 14th, 2002. Her memoirs La Traversée de la nuit and Le Secret de l’espérance (about her time at Ravensbruck) ensured that for thousands of other prisoners, their story was documented, never to be forgotten.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Antonioz fought tirelessly her whole life against injustice and poverty and the plight of deportees during the war. On February 21st, 2014, President Hollande announced that she would be interred in the Pantheon. It was a symbolic funeral; the coffin contained soil from her gravesite; her body remains with her beloved husband Bernard at Boissy en Haute-Savoie.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Antonioz was awarded the Resistance Medal and the Croix de Guerre.

The French Second Armored Division of General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque parades on the Champs-Élysées on August 26, 1944. © Wiki commons

The full story of these incredible women, and thousands more, who quietly and under the radar resisted in the best and bravest of ways they could, is told in Anna Sebba’s truly remarkable book, Les Parisiennes.

Women who had been so undervalued, powerless, before the war, stood up and were counted. A quote from Germaine Tillion at the end of Sebba’s book, sums them up.

“Indignation can move mountains. France in 1940 was unbelievable. There were no men left. It was women who started the Resistance. Women didn’t have the vote, they didn’t have bank accounts, they didn’t have jobs. Yet we women were capable of resisting.”

And thousands of them did just that.

Lead photo credit : German Luftwaffe soldiers at a Paris café, 1941. © Wiki commons

More in Parisienne Heroines, parisiennes, secret Paris, spy, war in france, women in history, World War II, ww11

REPLY