Jean Moulin and the Musée de la Libération

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

To celebrate and honor the liberation of Paris 75 years ago, on the 25th August 1944 when General Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division liberated the capital, the old Musée de la Liberation, sited above Montparnasse station, was moved into new, more accessible premises, a place redolent in the history of the Resistance, on Place Denfert-Rochereau.

The two pavilions flanking the entrance were designed by the architect Claude-Nicholas Ledoux in 1787, but it was what the pavilions concealed in WWII, that make this new site so significant.

100 steps down and 20 meters beneath the ground was a defense shelter, a bunker, built in 1938 by the public authorities as a place of safety from the threat of toxic bombs. It wasn’t until August 1944 that the Resistant fighter, Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, set up his headquarters in the bunker.

By then Jean Moulin, probably the most famous French Resistance leader during WWII, was already dead. Dead at the hands of the Germans, and more precisely as a result of torture by the infamous Nazi, Klaus Barbie.

General Leclerc outlived Jean Moulin by four years and the museum is named after both men: Musée de la Liberation-Musée du General Leclerc-Musee Jean Moulin. But it is Jean Moulin who still fascinates, who has captured the imagination of historians and the French public for the last 76 years.

Jean Moulin was perhaps an unlikely hero, although in most aspects of his life, Moulin often remained an enigma and unpredictable. His life, as his death, contains mysteries still not fully resolved, despite being pored over by historians both past and present.

What is indisputable however are the facts of his birth on 20th June 1899 in Béziers. His father, Antoine Moulin, was ambitious for his son (especially after the death of Jean’s older brother Joseph) and used his influence as councillor and freemason to not only further Jean’s career, but also to intervene in 1917 when Jean was 18, in his conscription into the army. (Jean Moulin was ever after to feel guilt at not fighting in WWI and doubtless this was a deciding factor in his determination to be part of the resistance movement more than 20 years later.)

Moulin’s father could not however fight the French government’s decision to bring forward the age of the compulsory draft and in 1918, Jean was torn from the refuge of his university and joined the 2nd Engineers in Montpellier. After months of training, his Commander in Chief, Foch, planned an offensive in Lorraine for 13th November. The armistice was signed two days earlier, on the 11th. Jean Moulin had still not come under fire nor fired a shot in battle, but was not spared the consequences of this most brutal of world wars. As engineers, their jobs were to bury the bodies of the last soldiers who had been killed in battle near Metz and he was a witness to the return of skeletal prisoners of war.

To be posted to Paris in 1919 and have his first taste of Bohemian life in Montparnasse where some of his cousins lived, must have been an impressionable experience. Moulin was an accomplished artist and loved paintings. In Montparnasse he could embrace both with a passion. His father’s influence was never far away though and in November he was demobilized and returned once more to Montpellier. (Moulin was to return to Paris and Montparnasse many times indulging in the licentious life Montparnasse always had to offer.)

Despite being an unsatisfactory, rebellious student, Moulin returned to university and took his law degree in 1921, becoming deputy chef de cabinet to Préfet Lacombe. It was the first of many posts that culminated in Moulin becoming the youngest Préfet in 1937 in the Aveyron dept.

Moulin’s love life did not run smoothly and after agreeing to an arranged marriage with Jeanette Auran, one of his cousins from Paris, Moulin and his father were dismayed when Auran’s father turned him down. He had neither liked Moulin, nor found his prospects good enough for his daughter. Moulin chose his next wife, Marguerite Cerruti, a professional singer, 8 years his junior aged 19. Cerruti, soon bored with the marriage, simply disappeared from their apartment one day without a word. They divorced two years later. From then on, Moulin would have numerous affairs, often with three women at the same time, each believing he loved them exclusively.

France throughout the 1930s and beyond was a hot bed of radical political parties, almost too numerous to mention. Moulin, although abandoning his father’s nineteenth century radicalism, still retained his belief in Republicanism and radical socialism. However, he was far from a zealot, and enjoyed his life as a successful administrator and a divorcee with a satisfying social life.

The constant underlying presence in politics, under whichever name, whatever banner, was always that of communism and the Comintern. The Comintern’s ambitions were global. Their aim was to set up the biggest Soviet spy ring that encompassed the army, navy and air force, the arms industry, ports, railways and government ministries.

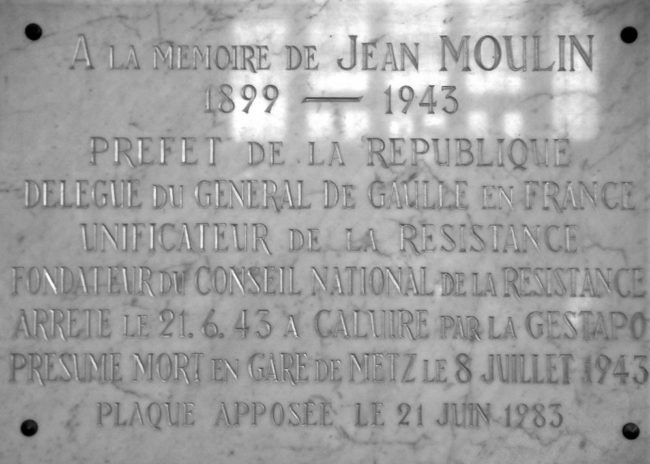

The Musée Jean Moulin, Paris. Image credit: Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Non communist organizations dedicated to ‘world peace’, ‘human rights’ or ‘anti-facist’– organizations that would attract influential people unwilling to ally themselves to the communist party– were a prime target for infiltration by the GPU, later more famously known as the KGB.

Lenin described these people dismissively as, ‘useful idiots.’ One such person, Pierre Cot, the leader of the ‘Young Turks’ of the Radical Socialist Party, had already named Jean Moulin his second in command in 1932 when he was serving as Foreign Minister under Doumier’s presidency.

Cot and Moulin were to remain entwined both politically and in the illegal involvement of shipping arms and planes to the Republicans fighting Franco, resulting in unsubstantiated claims that Moulin was assisting the Spanish Republican Army with arms from the Soviet Union and not from his position in the French Aviation ministry.

It was, of course, the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact, that had horrified both the Popular Front of the pro communist party, and the anti fascist Campaign for Peace, and had left their hopes in tatters and their sense of betrayal profound. A week later, Hitler and Stalin invaded Poland and two days later, France was at war. Moulin now had a tangible role to play in the defense of France. A role he determined he would not shirk.

Moulin was forced to return to Chartres to ensure the safety of the inhabitants living there. Chartres was soon to be filled with Parisians fleeing Paris and the city was in utter turmoil. Refugees looted shops and houses, gendarmes and soldiers fled the city and it was left to Moulin with the help of a couple of journalists, the ex mayor, four priests and twenty two nuns, to try to maintain order in a city of unfettered chaos.

On the morning of the 17th of June, Chartres surrendered to the Germans. By the same evening Moulin had been arrested and taken to the Hotel de France where he refused to sign a false declaration that three black, Senegalese French troops had raped and massacred women and children. Moulin was beaten for seven hours before being taken back into town and locked in a room. Moulin, afraid that more beating would result in his giving in and signing the document, cut his own throat with a piece of broken glass. He was found soon after by a guard and taken to the hospital. The ensuing scar Moulin would hide with a scarf. In most photographs of him afterwards, the handsome Moulin would be wearing what was to become his trademark neck covering.

After his release, Marshall Petain of the Vichy regime promptly dismissed Moulin calling him a ‘Radical’.

Unwilling to collaborate, Moulin left Chartres to join the French Resistance in Marseille and negotiate with the Free French, led by Charles de Gaulle who now had his headquarters in London. Moulin already had fake papers in the name of Joseph Jean Mercier, the name by which he was known throughout the rest of his time in the war. By September 1941, Moulin was in London, having traveled through Spain and Portugal and in October he had a meeting with De Gaulle who was so impressed by him, he gave him the almost impossible assignment of coordinating and unifying the various resistance groups. He was successful with three of the resistance leaders, Henri Frenay (Combat), Emmanuel d’Astier (Liberation) and Jean-Pierre Levy, (Francs-tireurs) who came together and formed Mouvement Unis de la Resistance. Moulin returned once again to London in March 1943 tasked with amalgamating other resistance movements who fiercely wanted to keep their independence.

It was impossible during this time that Moulin could escape suspicion and he was convinced that the Germans knew his identity. His meeting places, be they hotels or private houses, were always chosen because they had two exits, but in June 1943 a meeting with fellow resistance leaders was held at the home of Frédéric Dugoujon in Caluire-et-Cuire, a suburb of Lyon, in a house with only one exit.

Moulin and the other resistance leaders had been betrayed. They were arrested and taken to Montluc Prison in Lyon, where they were interrogated mercilessly on a daily basis by Klaus Barbie, head of the Gestapo there. Badly injured, Moulin revealed nothing to his captors even after he was driven to Paris by Barbie himself and the interrogations continued in the house of the senior Gestapo officer in France, Major Bömelburg, in Neuilly.

Tribute to Jean Moulin in the Imperial train station of Metz, in which he is believed to have died.

. Image credit: Wikipedia, Bava Alcide57 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Jean Moulin died on a train near Metz, heading for Germany. It is generally accepted that Moulin died from injuries sustained in a suicide attempt.

As for the traitor… Immediately the finger was pointed at René Hardy who was caught at the house and then released by the Gestapo. Others believed Hardy had just been careless, recklessly leading the Gestapo to the house. Others believed either this was the work of the communists, or he was betrayed by Gaullists. As with all conspiracy theories, the truth is often just out of reach.

Jean Moulin’s presumed ashes were buried in Père-Lachaise cemetery, but in 1964 were transferred with great pomp on December 19th to the Pantheon. André Malraux, writer and then minister of the Republic, gave one of the most stirring and moving speeches in French history.

The new Musée de la Liberation is a fitting tribute, not only to the courage of Jean Moulin, but to all members of the Resistance and the people who helped them during one of the darkest periods of French history. It is also a fascinating record of the events leading up to WWII culminating in the tumultuous week of insurrection leading to the Liberation of Paris.

Musée de la Liberation-Musée General Leclerc-Musee Jean Moulin

4, Avenue Henri Rol-Tanguay

Place Denfert-Rochereau, 14th arrondissement

Opening times-Tuesday-Sunday 10h-18h. Entrance free for permanent collections.

Lead photo credit : General Leclerc talks to his men from the 501e RCC. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

REPLY

REPLY