Black Lives Matter in Art History: Le Modèle Noir de Géricault à Matisse

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Another French Revolution has taken Paris by storm in, of all places, the elegant Musée d’Orsay, a tourists’ favorite because of its enormous collection of great 19th-century masterpieces, from academic to avant-garde, from Thomas Couture’s lascivious Decadence of the Romans (1847) to Boleslas Biegas’s brooding proto-Cubist Sphinx (1902). The best known among “the Moderns,” Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) shook the foundations of traditional French “received ideas” for art at the Salon of 1865 and continues to challenge our “received ideas” 154 years later, this time through the eyes of an American curator, Dr. Denise Murrell, the Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Research Scholar at the Wallach Art Gallery on Columbia University’s new Manhattanville, situated near the Hudson River side of Harlem.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883). Olympia, 1863.

First exhibited in the Salon de 1865. Oil on canvas, 130.5 X 191 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, RF 644. Photo © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Dr. Murrell’s doctoral dissertation on Manet’s model Laure became the exhibition Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today on view at the Wallach Art Gallery from October 24, 2018 to February 10, 2019. Through her beautifully organized selections of art and documentation, she invited “the viewer to reconsider Olympia as a painting that is about two women, one black and one white, who are both essential to achieving a full understanding of this work. . . [because] our understanding of Western modern art cannot be complete without taking into account the vital role of the black female figure, from Laure of Manet to her legacy for successive generations of artists.”

Posing Modernity grew from 140 objects to over 300 in the Musée d’Orsay’s Le Modèle Noire de Géricault à Matisse (The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse), including 73 paintings, 81 photographs, 17 sculptures, 60 prints and drawings, 1 photographic installation, and 70 auxiliary documentation (books, magazines, posters, letters, etc.), on view from March 26th through July 21st, 2019. The New York show started in the mid-19th century and ended with post-modern art. The Paris show starts in the late 18th century and ends with Glenn Ligon’s Some Black French People/Des Parisiens Noirs (2019), a work especially created for the cavernous great hall in the middle of the Musée d’Orsay.

Anonymus, the Royal Manufacturer of Sèvres. Am I not a man? A brother?, 1789. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Altogether the Paris show offers a vast array of visual and textual sources that provide an extremely deep dive into history of black people represented in French art. The oldest work is a porcelain medallion of a slave in chains, pleading for recognition and treatment as an equal: “Am I not a man: a brother?,” created in 1789, the year of the first French Revolution. Aside from Glenn Ligon’s installation, the youngest work is by post-modern Congolese artist Aimé Mpane. His mosaic Olympia II (2013) casts Manet’s duo in reverse: the courtesan is black and the maid is white. This repositioning of the principal actors in Manet’s Olympia visually reinforces the educational narrative of entire endeavor: the exhibition, the catalogue, the symposia, and the performances. For here we note that the traditional approaches to art history stand in stark contrast to values we need to fully grasp the impact of modernity, launched, according to some, as far back as the Industrial Revolution. The shift from a predominately Eurocentric reception of art to a culturally-diverse reception of art can reveal unacknowledged truths that will, hopefully, set all of us free from racism of every kind.

Édouard Manet, La négresse (Portrait of Laure), 1863. Oil on canvas, 24 × 19-11/16 in. (61 × 50 cm). Collection Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turino. Photo: Andrea Guerman, © Pinacoteca Giovanni e Marella Agnelli, Turino.

Back in 1865, when Olympia faced the public for the first time, Manet’s confrontational white prostitute (posed by the model Victorine Meurent) received the lion’s share of commentary and criticism, unleashing a trend that calcified in art history’s literature for most of the next hundred years. Meanwhile, the equally visible black maid remained either ignored or vaguely interpreted as another erotic element as well as a luxurious accessory, along with the expensive shawl, indicative of Olympia’s rank and price among the demimondaine (the flipside of respectable society). Dr. Murrell with her colleagues in Paris set out to change this perception of the black maid in the painting and the black model Laure who posed for the role in Manet’s bold statement about modernity in the 1860s. With text panels and maps as our guides, we learn about the life of Manet’s model Laure, the black communities in Paris, numerous immigrants from Francophone countries, and French-born black citizens. We also learn about the black American celebrities who introduced Afro-Caribbean entertainment and authentic nightclub jazz. The galleries are divided into twelve categories: “New Insights,” “Géricault and the Black Presence,” “Art Against Slavery,” “Literary Mixed Races,” “In the Studio,” “Surrounding Olympia,” “On Stage,” “The Black Force,” “For and Against the Colonial Empire,” “Négritude in Paris,” “Matisse in Harlem,” and “I Like Olympia in Black.”

Marie Guillemine Benoist (1768-1826)

Portrait of Madeleine, 1800. Also called Portrait of a Black Woman. First exhibited at the Salon de 1800 as Portrait d’une Négresse. Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, INV 2508. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Gérard Blot

Let us begin in the first section “New Insights” where Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine dominates with her sober neoclassical beauty. On loan from the Musée du Louvre, this painting had been titled Portrait of a Negress (a racist term) until a fairly recent decision to revise the title to Portrait of a Black Woman, perhaps in the 1990s. The new title Portrait of Madeleine redirects our consideration of the sitter from an anonymous ethnographic curiosity to the plight of an individual living in France during the first short-lived period of abolition. Madeleine was an emancipated slave from Guadeloupe brought to Paris by the artist’s brother-in-law. The artist was one of the rare professionally active women who had trained in Jacques-Louis David’s studio. In her portrait of Madeleine, Benoist imagines her sitter in an allegorical role. Dressed in a virginal white dress folded down to reveal one bare breast, there seems to be a deliberate visual emphasis performed by the bright red ribbon tied just beneath this eroticizing exposure.

Benoist’s entire concept seems to be based on Marianne, the French symbol for Liberté. For here, with the pristine white and scarlet red hugged by a steely blue shawl draped over Madeleine’s chair, the combination invokes the blue, white and red of the French flag, le tricolore, and its Republican spirit: “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” Did Benoist portray Madeleine as a person? Or did Benoist enlist her likeness to advance a political agenda? Or does Madeline represent for Benoist the concept of “liberty” because she was a recently freed slave?

Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863). Study of the model Aspasie, ca. 1824-1826. Also called A Mulato Woman, a study based on the nude; Aline, a Mulatto Woman; Portrait of Aline. Oil on canvas, 81 × 65 cm. Montpellier, Musée Fabre,. Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole, INV. 868.1.36. Photo © Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole / photographie Frédéric Jaulmes

By 1800, the date of Madeleine’s portrait, slavery had been outlawed in France and its colonies. It was reinstated in 1802 and then outlawed again in 1848. If we compare Benoist’s Madeleine to Eugène Delacroix’s Aspasie (c. 1824-26), we might decide that the bare breasts in both paintings deliberately eroticizes the subjects, compromising the dignity and modesty of both women. With that in mind, the correction of the Benoist title further complicates our reception. For now that we know the sitter’s name and see her an immigrant, we wonder if she willingly agreed to sit semi-nude or was forced into this position as another of her domestic duties. Moreover, did she suffer such humiliations daily? Madeleine’s and Aspasie’s Fornarina-esque poses enforce a controlled composure that does not betray their minds. When Delacroix painted the model Aspasie three times, clothed and semi-nude, slavery had been part of French life for the last twenty years. Born in 1798, this Romantic artist had never known a French society without slavery at this point, 1824-1826. We do know that he had already painted the Massacre of Chios, presented in the Salon of 1824, which communicates his sympathies for the victimized Greeks slaughtered and enslaved by the Turks. Did Delacroix feel the same way about African slavery in France and the French colonies?

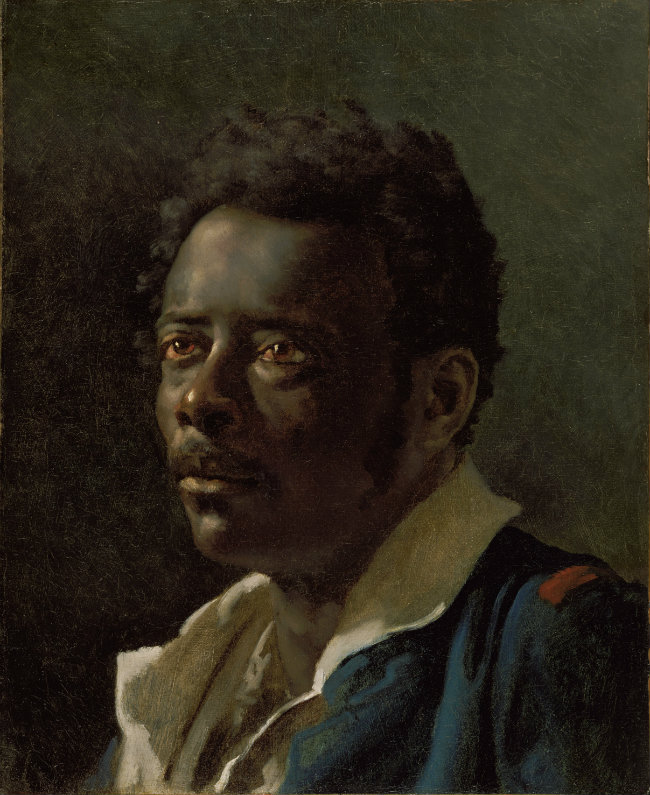

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824). Study of a Man, based on the model Joseph, ca. 1818-1819. Also called The Black Man Joseph. Oil on canvas, 47 × 38,7 cm. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.PA.407. © Photo Courtesy The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Delacroix’s Aspasie appears in the section called “Géricault and the Black Presence” where we confront the history of slavery in the French colonies and the Haitian revolt again it. Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) tried to introduce an abolitionist’s perceptive. As Marilyn Brouwer explained in her excellent essay “Favorite Paintings in Paris: Le Radeau de la Méduse,” this enormous Romantic masterpiece imagines the rescue of survivors stranded for two weeks on a jerrybuilt raft constructed from the remains of their ship the Medusa, originally bound for the French territory Senegal. With about 400 passengers and crew, the ship ran aground off the west coast of Africa, near today’s Mauritania, on July 2, 1816.

Unable to budge, the lifeboats could accommodate only 250 people, who were mainly the white French colonists. The rest, 150 passengers and crew, were placed on a raft that submerged immediately under their weight. At first the lifeboats supported the raft with ropes attached to their bows. But this solution hindered the course of these tiny craft. The lifeboat passengers decided to release the raft, forcing the surviving crew to navigate on their own. Over the next two weeks, most of these raft occupants died from exposure, starvation and drowning. There was also cannibalism. The whole disastrous voyage could be blamed on the newly restored Bourbon King Louis XVIII, who appointed an incompetent admiral with no experience commanding a major vessel.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824). Study of a Back (based in the model Joseph) for the Raft of the Medusa, vers 1818-1819. Oil on canvas and black stone, 56 × 46 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, en dépôt à Montauban, musée Ingres, RF 580. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Philipp Bernard

The Méduse was one of three ships that set out to settle Senegal. The other two reached their destination because they avoided the shoals along the coastline, adding time to their voyage, but ensuring a safe arrival. In the sketch of Géricault’s Joseph, a well-known model among contemporary academic artists, we see a study for the black figure who vigorously waves a scarf toward the horizon in the finished masterpiece. In Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, a tiny depiction of the Argus, which eventually rescued the surviving 15 people found on the raft, appears in the distance. The black model Joseph was a favorite at the time and also posed for Théodore Chassériau, a student of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix.

The child-prodigy Théodore Chassériau was himself a mixed-race immigrant from the French colonies, the son of a French administrator in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and a French landowner’s Creole daughter. Born in El Limón, Samana, a Spanish colony in Santo Domingo, today’s Dominican Republic, his father sent him to Paris to live with his much older brother, who placed him in Ingres’ studio at the exceptionally young age of 11. As we see in this exhibition, some of his works refer to racial differences in life and art, such as Esther Preparing to Meet Ahasuerus (1841) and Othello Smothering Desdemona (1849).

Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856). Esther Preparing to Meet King Ahasuerus, 1841. Also called La Toilette d’Esther . First exhibited at the Salon de 1842. Oil on canvas, 45 × 35 cm

Paris, musée du Louvre, département des Peintures, RF 3900 . The Baron Arthur Chassériau Bequest, 1934

Chassériau’s Esther belongs to the section entitled “Autour Olympia/Surrounding Olympia,” but thematically could belong to “Literary Mixed Race/Métissage Littéraire” because it features the biblical story about racial Otherness for a Jewess passing as a non-Jew in ancient Persia. One wonders if Chassériau identified with Esther in his real life in Paris. Chassériau’s Othello Smothering Desdemona (1849) can be found in the “Métissage” section because it illustrates a scene in Shakespeare’s play about a Moor experiencing racism, love and betrayal. Chassériau painted and engraved numerous scenes in this tragedy about the general Othello, his Venetian wife Desdemona, and his treacherous ensign, Iago. For this exhibition, Othello serves as a model of racial differencing in European art, but for those who know Chassériau’s life, one may consider some parallels. As a Creole in Paris, born into a colonial governor’s family, Chassériau enjoyed access to exclusive salons and well-known intellectuals. Yet, he did not marry. One wonders whether his mixed racial status prevented women from accepting his offers. It is assumed that the model for Esther was his mistress at the time, Clémence Monnerot, who eventually married the perpetrator of racist mythology, Arthur de Gobineau. Perhaps, Joseph modeled for figure of Hegai, the harem’s eunuch, seen here offering Esther an elaborate box as she completes her toilette.

Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884). Portrait of Alexandre Dumas in Russian Outfit, 1859. Oval proof mounted on gray paper mounted on cardboard, 25,2 × 19,3 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, PHO 1986 11

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay) / image RMN-GP

The section “Literary Mixed Race/Métissage Littéraire” also brings into focus another aspect of the exhibition: portrait photographs commissioned by the sitter. Here the great literary bon vivant Alexandre Dumas père, author of The Count of Monte Cristo (1844-46) and The Three Musketeers (1844), majestically commands the space in Gustave Le Gray’s composition. This work and other photographs are paired with various caricatures of Dumas that expose the racist attitudes leveled at this son of French aristocrat Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie and his Afro-Caribbean former slave Marie-Cessette Dumas. Born in Saint-Domingue (Haiti), Dumas arrived in France at age 14 to study and make appropriate social connections.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883). Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire’s Mistress, ca. 1862. Oil on canvas, 35 7/16 x 44 ½ inches (90 x 113 cm). Budapest, Szépmûvészeti Museum. Source: Public Domain

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867). Portrait de Jeanne Duval, 1855. Pencil and ink, 20,6 × 14,5 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, RF 41644

The poet Charles Baudelaire’s long and tempestuous relationship with the Creole actress Jeanne Duval (1820-1862) lasted nearly 20 years and inspired several poems in Les Fleurs du Mal, published in 1857. Duval came to France from Haiti in 1842 and met Baudelaire shortly afterward. She too was his model for this sketch from 1850. By 1859, Duval had been stricken with paralysis and cared for in a sanatorium at Baudelaire’s expense. In Manet’s portrait, we see the darkened eyes, wane posture, and odd protruding left leg, perhaps evidence of her invalid state. She was about 42 years old. Stretched out on a large deep green sofa, Duval seems diminished by the abundance of white all around her: the voluminous skirt, the fashionable puffed sleeves and the diaphanous curtains behind her. However, Duval wasn’t small. Françoise Cachin describes her in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s catalogue for the exhibition Manet: 1832-1883 as a “tall and angular” person. Baudelaire (1809-1867) suffered a massive stroke in 1866, leaving him semi-paralyzed until his death more than a year later.

Félix Nadar (1820-1910). Maria l’Antillaise, between 1856 and 1859. Proof on brown paper, 25 × 19 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, PHO 1981 36.

Photo © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Féix Nadar’s photograph Maria l’Antillaise (ca. 1856-58) in the section “Métissages Littéraires” informs our understanding of Manet’s portrait of Laure (1862), wherein we see a woman of color dressed in contemporary Parisian clothes wearing the typical Caribbean stripped scarf. Here is a hybrid, a métissage, of modern and ethnic fashion statements.

Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870). Women with Peonies, 1870. Originally titled Négresse aux pivoines

Oil on canvas, 60 × 75 cm. Washington, National Gallery of Art, collection de M. et Mme Paul Mellon, 1983.1.6. © Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, NGA Images

We see this again in Frédéric Bazille’s Woman with Peonies (1870), placed in “Surrounding Olympia.” The combination of typical working-class Parisian clothes and a specific Caribbean accessory seems to deliberately identify the peddler as an immigrant contributing to the new urbanized French city. Bazille also pays homage to his mentor Manet, as he quotes Olympia’s maid cradling a bouquet of flowers.

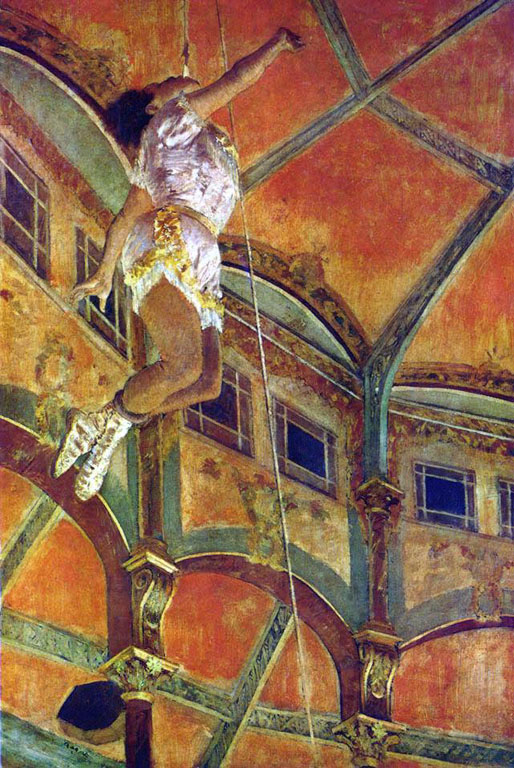

Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Miss Lala in the Fernando Circus, 1879.

Oil on paper, 117,2 × 77,5 cm. London, National Gallery, on loan to the City Gallery The Hugh Lane, Dublin, since 1979, NG4121. © National Gallery, London, UK

The Otherness of actors and entertainers appears in the section called “On Stage.” Manet’s Jeanne Duval might qualify for this section by virtue of her occupation, but her identity for the exhibit does not fit here. Rather the curators considered the influence of art nouveau posters which exaggerated facial and body features as part of its mannerist aesthetic. The avant-garde techniques and compositions account for Edgar Degas’s unusual perspective in Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando (1879).

Known for her death-defying feat of holding a rope by her teeth way above the crowd seated in the massive octagon domed building that housed the Cirque Fernando (renamed the Cirque Medrano, made famous in Picasso’s Rose Period works of art), this shimmering painting captures the young acrobat spinning high above us, her legs dangling in a controlled balletic plier. We know that Edgar Degas spent several evenings in January 1879 watching Miss Lala and he produced several sketches besides his well-known painting from the National Gallery in London. Here, as in several other cases, the curators brought together a clutch of artworks, documents and illustrations to explain one major masterpiece.

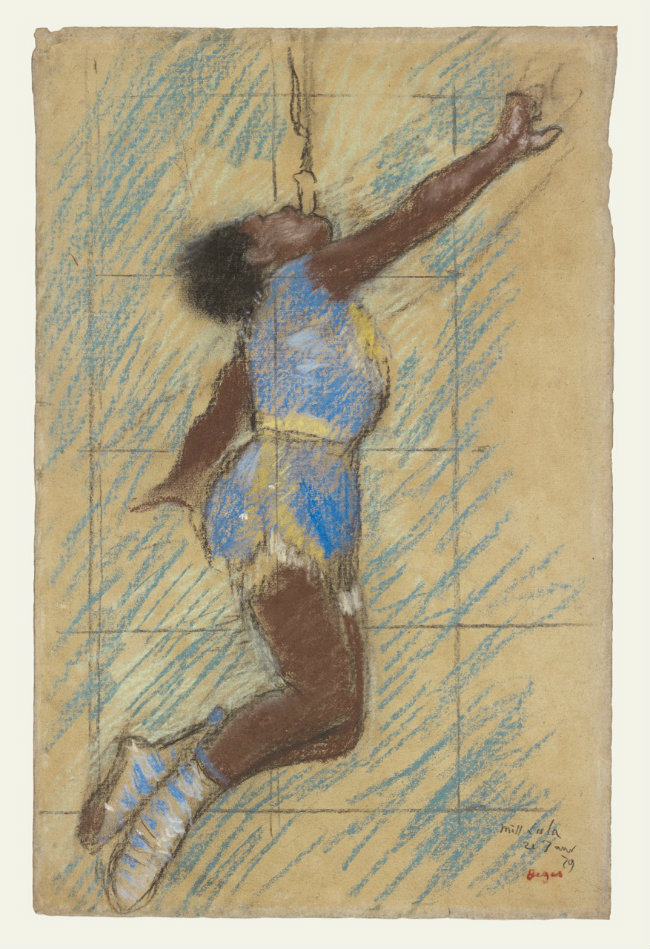

Edgar Degas (1834- 1917). Miss Lala in the Fernando Circus, 1879. Pastel, 61 × 47,6. London, Tate, presented by Samuel Courtauld 1933, N04710

Miss Lala’s real name was Anna Olga Albertina Brown. She was born in Stettin, Germany (now Sczcercin, Poland) on April 21, 1858 to Wilhelm Brown, a black German, and Marie Christine Borchardt, a white Prussian. Part of the Troup Kaira, Anna started to perform at 9 and became an international star by 21. Paris adored her! In 1879, the date of Degas’ sketches and painting, she was part of the Keziah Sisters and the Folies Bergère. She then partnered with Theophila Szterker/Kaira la Blanche and became one of Deux Papillons (The Two Butterflies). In 1888, she married the American contortionist Emmanuel (Manuel) Woodson. They had three daughters who became the Three Keziahs. Anna/Olga Woodson applied for a U.S. passport in 1919. There is no further information about her life or death.

Walery (1866-1935), Josephine Baker, no date, Postcard,14 × 9 cm, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 4°ICO PER 1326, classeur 23, photos no 140. © Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Augmenting “On Stage” is another section dedicated to Josephine Baker, “The Black Force,” whose life and legacy appear in a wonderful Bonjour Paris article by Marilyn Brouwer. Another American dancer Katherine Dunham inspired Henri Matisse’s dazzling cutout Creole Dancer (1950). Here the hot colors painted on sheets of paper, shaped by the scissors of the French modern master, seem to swirl around a dancer like Dunham when she performed.

Katherine Dunham (1909-2006) in “Tropical Revue”

at the Martin Beck Theatre, 1943 (Source: Public Domain)

Katherine Dunham was born on June 21, 1909 in a Chicago hospital to a father from a West African and Madagascar background and a mother from a French-Canadian and Native American background. They lived outside of Chicago in Glen Ellyn, Illinois. After her mother died, her father remarried and moved the whole family to the white suburban Jolliet, Illinois. Dunham attended the University of Chicago, majoring in dance, anthropology and philosophy. She studied with a classical Russian ballet dancer and several modern dancers, bringing both traditions into her own choreography. She traveled on grants to study dance in Jamaica, Trinidad, Tobago, and Haiti, among other Caribbean locations, and brought all these influences into her creative work.

She opened her dance school in Chicago in 1933. Her New York studio, the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theater, opened in 1945. It became a mecca for serious dancers and actors, such as James Dean, Gregory Peck, Jose Ferrer, Jennifer Jones, Shelley Winter and Marlon Brando. For decades she taught, danced, choreographed, and published books. She toured with her dance company through the US, Europe, West Africa and South America. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Dunham to the post of technical cultural adviser for the Senegalese government. In that capacity, she trained the Senegalese National Ballet. Matisse’s 1950 Créole Dancer may be based on her company’s performance entitled Caribbean Rhapsody, staged in London and Paris in 1948. Katherine died on May 21, 2006 at the age of 96.

Félix Vallotton (1865-1925). Aïcha, 1922. First exhibited in the show Félix Vallotton at Galerie Georges Petit, 1922. Oil on canvas, 100 × 81 cm. Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Foundation for the Hamburg Art Collection HK-5739

In the section “Négritude” (Black and African Pride), we find beautiful portraits of black models who posed for young modernist artists. One example is Félix Vallotton’s Aïcha (1922), a magnificent portrait of the actress/performer Aïcha Goblet, draped in an opulent emerald green dressing gown falling slightly off her shoulders and just above her breasts, revealing her lovely dark skin adorned by a red beaded necklace. Her silver satin turban shines above her averted gaze. This was her signature look. Once a member of the spiritually-invested Nabi movement, Félix Vallotton changed direction after World War I, embracing the return to classicism prevalent among formerly avant-garde artists. With this stylistic choice in mind, Vallotton invents a modern Venus, exuding a commanding self-possession that is elegant and dignified, a departure from Olympia in the direction of celebrating womanly grace.

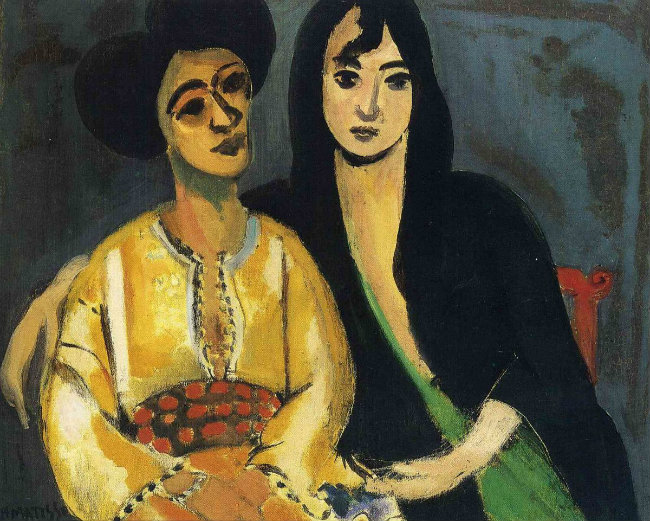

Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Aïcha et Lorette, 1917. Oil on canvas, 37,5 × 46,4 cm. Private Collection, 2012

Aïcha Goblet was born France to a circus family. Her father was a juggler from Martinique and her mother was French. By 6 years old, she performed riding bareback on a horse. At 16 she ran away, becoming a model for the Bulgarian artist Jules Pascin, then an actress. At one time, she lived at the Villa Falguière, an artists’ colony, and cooked for people short of money. André Salmon recalls: “Long before Josephine Baker launched the fashion of banana belts, Aïcha wore, at wild parties in Montparnasse, her diminutive raffia skirt.” Her gold business card read “Aïcha Goblet, artiste.” Salmon reassures us that Aïcha could certainly hold her own during any conversation within their art circles, at the tables in cafés or in front of the easels inside the studios. Besides posing for Valotton, Pascin, Matisse, Aïcha sat for Moïse Kisling (also on view), Man Ray and Amedeo Modigliani.

William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Portrait of Woman with Blue and White Striped Blouse, ca. 1940–42.

Tempera on paperboard, 28 × 22-1/16 in. (71.1 × 56.0 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.,

Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Among the few African-American artists in Le Modèle Noir, we find William H. Johnson’s Portrait of a Woman with Blue and White Striped Blouse, which demonstrates the influence of the School of Paris, especially Matisse, on this early modernist artist. Johnson enjoyed the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and knew numerous major artists, white and African-American, throughout his active career. He left New York in 1927 to study in Paris, then in the South of France. There he met the Danish artist Holcha Krake (1885-1944) whom he married in 1930 after returning to the US briefly in 1929. They settled in Denmark in 1930. In 1947, grieving the loss of Holcha who died of breast cancer, Johnson exhibited strange behavior, which was finally diagnosed as syphilis-induced paresis. He went back the US and spent his final 20 years in Central Islip State Hospital.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Woman in White Dress (Woman in White), 1946. Oil on canvas, 96,5 × 60,3 cm. Des Moines, Des Moines Art Center, 1959. Gift from Mr. John and Mrs. Elizabeth Bates Cowles. © Photo : Rich Sanders, Des Moines, IA. © Succession H. Matisse

The Black Model from Géricault to Matisse will always be remembered as a watershed moment in the history of art and museum education as its legacy transforms our reception of black people depicted in visual terms. Having restored the names and identities to many black models who posed for well-known artists, the curators ask us to revise our ingrained notions and renegotiate iconography, bearing in mind the history and circumstances of the model as well as the artist who interprets him or her. Above all, this exhibition reminds us again that art is never meant to be read only one way. For all art belongs to all of us and the questions we pose are indeed an aspect of what Dr. Murrell means in her original title for the New York exhibition, Posing Modernity. For it was Manet who posed the question: what makes the “modern” modern? And it was Dr. Murrell who noted the question and formulated an answer: black and white people living and working together.

Kudos to the entire curatorial team: Cécile Debray, Director of the Musée de l’Orangerie; Stéphane Guégan, Advisor to the president of the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie; Denise Murrell, Postdoctoral Research Fellow sponsored by the Ford Foundation at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University; and Isolde Pludermacher, Chief Curator of Painting at the Musée d’Orsay.

And to their colleagues who contributed to the catalogue: David Bindman, Professor Emeritus of Art History, University College London; Anne Higonnet, Ann Whitney Olin Professor, Barnard, Columbia University; Anne Lafont, Art Historian and Director of Studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (The School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences); and Pap Ndiaye, Historian and Professor at Science Po (Paris Institute of Political Studies).

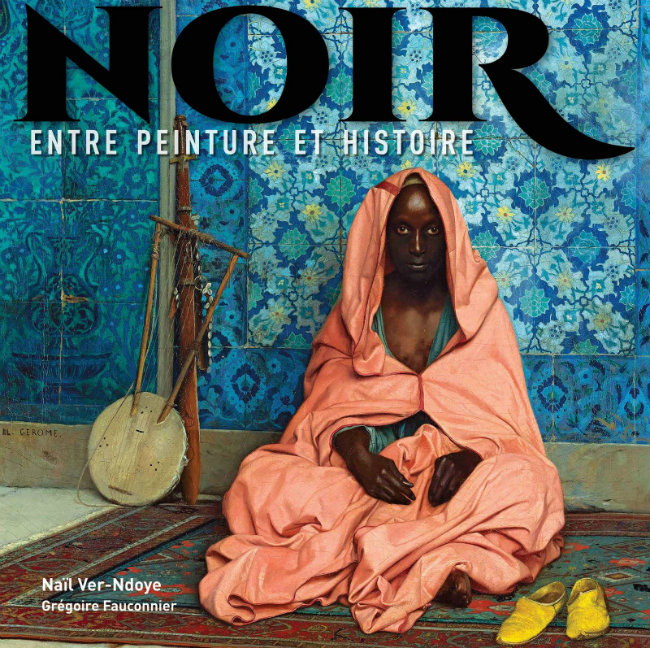

Noir entre peinture et histoire (Black Between Painting and History)

Further reading:

The museum’s press release rightly points out: “For roughly the past thirty years, the representation of black people has become a topic in the history of art that has been widely explored on both sides of the Atlantic . . . [but] to date, no exhibition has ever attempted to explore the centuries-old civilizational phenomenon through the French Revolution to the start of the twentieth century.” This assertion needs further clarification.

The Image of the Black in Western Art, begun in 1976, published its volume on antiquity. Since then the series grew to five volumes, the most recent on the twentieth century, published in two parts, in 2014. Therefore, the research and analyses of black figures in art has received significant attention for several decades within a very small community of scholars. Each volume is extremely expensive, limiting its accessibility to most members of the general public. At best, one can borrow these books from a public library or university library that has purchased the entire series.

For those of you who read French and would like a more comprehensive approach at a reasonable price, I recommend Noir entre peinture et histoire (Black Between Painting and History) by Nail Ver-Ndoye and Grégoire Fauconnier (2018), available on the internet. The reproductions are excellent; the prose is easy to read, even for an intermediate student of French.

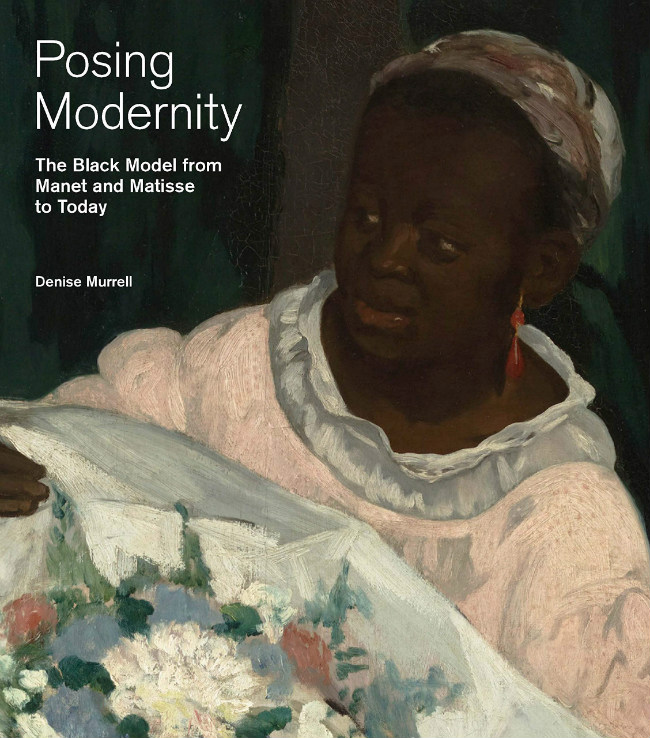

Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today

For those of you who read only English, I highly recommend the exhibition catalogue for Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (Yale University Press, 2018). It is brimming with examples from the New York exhibition and more. The photographs of the daguerreotypes provide a better view of these objects than studying them in person. Moreover, this book is a landmark in art historical scholarship and may eventually become a collector’s item.

Lead photo credit : Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904). Study for a the woman in Slave Market in Cairo, ca. 1872. Oil on canvas, 48 × 38 cm. Private Collection. © Photo courtoisie Galerie Jean-François Heim – Bâle

More in Orsay, Orsay Museum

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY