Favorite Paintings in Paris: Le Radeau de La Méduse by Théodore Géricault

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Fifty years ago on my first ever visit to the Louvre, I stood enthralled in front of Géricault’s vast masterpiece, Le Radeau de La Méduse.

I had never seen anything like it.

I have never been to the Louvre since without searching it out, squeezing onto the bench opposite the painting, and soaking it in. It still entrances me. I remember vividly on my first viewing of it, that what had stopped me in my tracks was Géricault’s depiction of flesh, the flesh and muscle showing under the sea-soaked, translucent shirts of the ship-wrecked sailors. It was breathtaking in its realism, but more than that, emotive, full of pathos; this was wet flesh you could touch; you could almost feel the desperate coldness of the salt water through their clothes.

Obsessed by the technical details of dead bodies and a determination to be historically correct, Géricault set up his studio opposite Beaujon hospital. Here he not only studied and made sketches of bodies in the morgue, but also brought back severed limbs to his studio to observe and make notes on the process of their decay. Nothing was too repulsive or macabre for Géricault; he had earlier been exposed to victims of plague and insanity, and a severed head borrowed from a lunatic asylum sat on the roof of his studio for two weeks while he sketched it.

For an artist unafraid to tackle unpleasant and shocking subjects, the disaster that engulfed the Raft of Méduse was manna from heaven.

On July 2nd 1816, the French naval frigate Méduse ran aground off the coast of Mauritius. The ensuing scandal was to engulf France. The captain of the Méduse was Viscount Hugues Duroy de Chaumareys who had barely sailed in the previous 20 years. His appointment was later seen as an act of political preferment. Due to a navigational error, the ship drifted 100 miles off course and lodged itself on a sandbank. All efforts to refloat the ship failed and three days later traumatized passengers and the crew on the frigate’s six life boats attempted to make for the African coast 60 miles away. The six life boats proved to be woefully inadequate to accommodate the 240 crew and 160 passengers. 250 people boarded the six life boats, 17 crew members elected to stay on board the Méduse, and at least 146 men and one woman were forced to disembark onto a hastily constructed raft. The raft was meant to be towed by the Captain and crew in the life boats but after several miles, the raft was set loose. The only provisions on the raft were a bag of biscuits, two casks of water and six casks of wine. (I make no comment on the four extra casks of wine.)

What was to follow became the stuff of nightmares and a shameful event in history never to be forgotten. When the raft was miraculously rescued 13 days later by the ship Argus, only 15 survivors remained. The French navy had made no particular effort to find the raft and the Argus spotting the raft had been purely accidental.

Maddened by hunger and thirst, the strongest had slaughtered the mutineers and the weakest and resorted to cannibalism, eating the flesh of their erstwhile companions. Many had already died of starvation, been thrown overboard, killed, or in despair had slipped off the raft into the sea. All in all, 132 people lost their lives by whatever means and by whoever’s hands in the 13 days most hellish days imaginable, at sea.

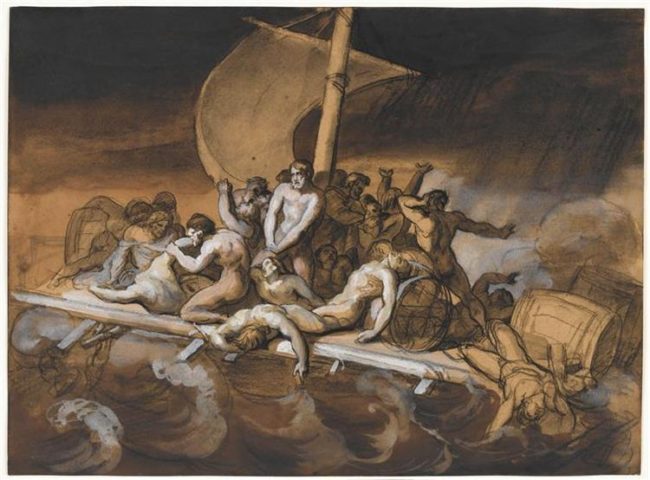

Géricault chose the moment when some of the survivors saw the Argus on the horizon to portray the inestimable depths of horror that had overtaken them and the glimmer of hope of a rescue, probably long since abandoned.

The painting is immense. Measuring almost 194 inches by 283 inches, the background figures life-sized while the foreground figures are almost twice life-sized, making it inescapable to draw back from the painting. (When the painting was shown in London and hung much lower, Géricault realized the impact this had made on the viewer, the forced participation and immediacy at this level of intimacy.)

The painting is a study in subdued browns– even the sea is muddied. The dawn breaking over the Argus in the top right of the painting is the only light illuminating it. The waves are merciless; the raft so ramshackle it seems impossible that it can withstand another pounding from the sea.

But it is the survivors, some barely alive, almost all broken, dead eyed in despair, clinging to the raft, that captures almost all our attention.

There are dead too; an old man holding on to his dead son whose legs are already trailing uselessly in the water and resting on a dead body, is hunched over, racked with silent grief and utter hopelessness. The dead are draped across the raft, some about to be swept away by the next wave, but there are the living too, standing, waving and leaning towards the edge of the raft nearest to the horizon and the tiny speck of the Argus. The painting is almost in two halves: the dead, dying and those who have given up, at the forefront of the picture, the survivors who now have hope, are upright, with their backs to us, almost triumphant, celebratory in being alive.

Géricault’s obsession with this painting resulted in numerous sketches, paintings, and a scale model of the raft being constructed, plus preliminary sketches of various and precise moments of the disaster, including the cannibalism, mutiny and actual rescue, until this final moment was decided upon.

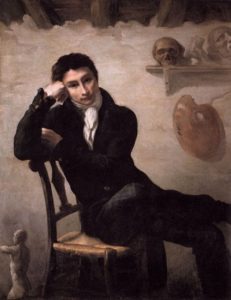

He met with two of the survivors, and traveled to Le Havre, despite illness, to study waves and storms in the English Channel. Géricault was a tortured soul, prone to mental illness and ill health and this painting consumed him almost to breaking point. During the actual painting, Géricault lived a monastic life, barely leaving his studio, sleeping in a small adjacent room and having his meals brought in. It took eight months to complete the painting during which time he insisted on total silence.

Understandably completely exhausted, Géricault awaited the affirmation in 1819 of the Paris Salon.

The reviews were mixed. Although Géricault’s Le Radeau de Méduse was the star of the exhibition– which included 1300 other paintings, sculptures, architectural designs and etchings– and indeed was awarded a gold medal, many critics were repulsed and found his realism “a far cry from the ideal beauty” of classicism.

Géricault had more success in London when the painting was exhibited in 1820 where it was shown at William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly. Géricault earned almost 20,000 francs from his percentage of visitor’s fees, far more than he had made in Paris.

Fortunately, Géricault had an influential and steadfast admirer, Comte de Forbin, who just happened to be the curator of the Louvre. After Géricault’s death, the painting was bought from his heirs and now is an unmissable attraction, dominating Room 700 on the first floor of the Denon Wing.

Perhaps the most astonishing fact of this magnificent painting is that Géricault was only 27 years old when he completed it. He died seven years later of years of chronic illness and tuberculosis.

Père-Lachaise cemetery holds his tomb. A bronze figurine, brush in hand, adorns the burial place of this young, astounding artist.

Fittingly, a low relief panel of Le Radeau de la Méduse is set into the tomb below Géricault’s figurine.

Two hundred years later, visitors to the Louvre still stand and stare in wonder at this much loved masterpiece by an artist whose life was cut short far too early.

Related article: Favorite Paintings in Paris: L’Absinthe by Edgar Degas at the Orsay

Lead photo credit : Le Radeau de La Méduse, 1818 - 1819, Louvre © Public Domain

More in Louvre