The Smart Side of Paris: The Lottery

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In a country renowned for its social services, few are less well known than the office dedicated to the well-being of lottery winners. Commissioned to helping the nouveau riche avoid the insanity induced by serendipitous wealth, the FDJ Group (Groupe FDJ) is an arm of the Commitment and Responsible Gaming Group of France’s national lottery system. Isabelle Césari heads the group and her passion for helping people transition to new lives after becoming suddenly wealthy is so sincere that she has given a TED talk on “How to Support Lottery Winners”; her goal is to demonstrate how the group helps people “in the transition from pleasure to happiness.” (For those who understand French fairly well, here is a fun podcast on the French lottery system).

While today the French lottery makes average people wealthy and benefits charitable causes, those were not always its goals. Historically, state-sponsored lotteries were designed to guarantee income to the Crown, but they were notoriously unreliable because they sought to guarantee winnings for the state. Lottery tickets were often sold for years until enough were sold to guarantee a profit. In essence, they functioned like raffles. Without a fundamental understanding of the laws of probability, which were just being formulated in the 17th century, mistakes were made.

One such mistake goes down in the history of lotteries as among the most fortuitous for the world of literature, and nearly ruinous for the French crown. At a dinner party in 1728, Voltaire and the scientist Charles Marie de la Condamine were discussing the French lottery. They determined that the lottery had a flaw in that tickets were being offered only to a limited number of people (bond holders) and that opportunities to win were to be disbursed regardless of the “price” of the bond purchased. Bond holders could divide their large purchases into many smaller ones, purchase all the available tickets, and win every time. Voltaire, La Condamine, and others formed a “society,” that is, a syndicate of ticket buyers, bought up nearly all the tickets month after month, and won several million francs. The government declared fraud, but the courts ruled that Voltaire and La Condamine played within the rules that the lottery’s organizers themselves had defined. The French government shut it down before Voltaire and Company shut down the French government. (It is odd to think that without the lottery, the world might not know Voltaire!)

The Philosophers’ Supper (Huber). Voltaire raises his hand to impose silence. To his left Diderot, then Father Adam, Condorcet, d’Alembert, Abbot Maury and La Harpe. The scene takes place in Ferney in 1772. Public domain

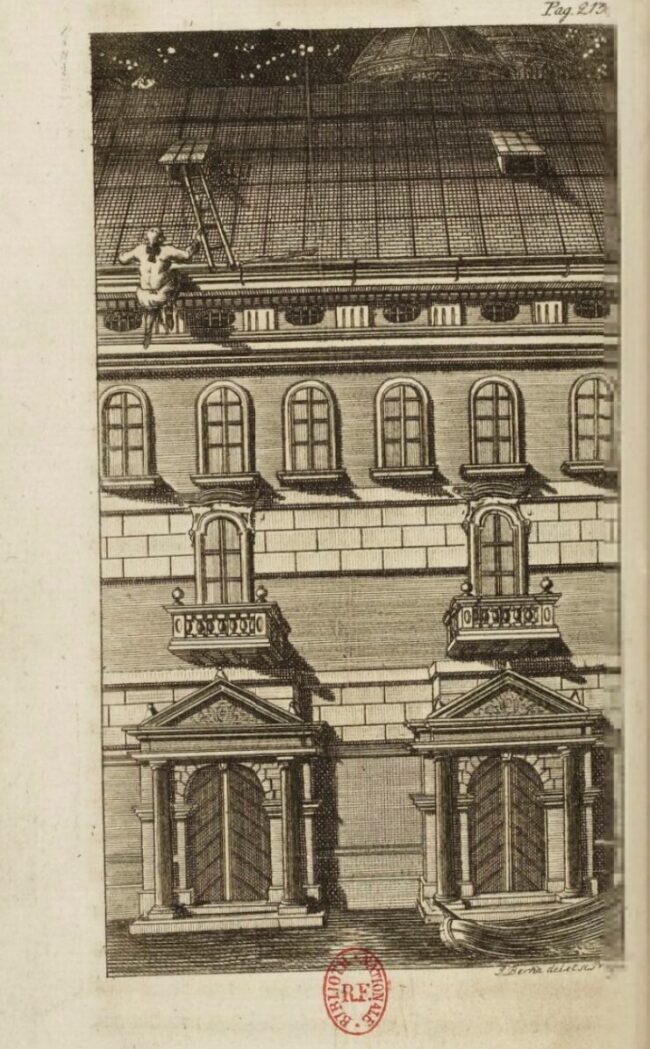

Because of this error, the French Lottery lay dormant for about 30 years, the government returning to the meager taxes that could be harvested from the poor. Various ministers recommended its resurrection, but their suggestions were always quashed for fear of similar losses. But in January of 1757, a prisoner escaped from the feared “I Piombi” prison of the Venetian Inquisition, walked to Paris, and looked up an old friend: the aging, brilliant financier, Joseph de Pâris-Duverney. Thanks to Beaumarchais, Pâris-Duverney had been able to finance the construction of the École Militaire (1751), which was, in 1757, struggling to keep afloat financially. The wily escapee claimed to have a surefire plan to keep the École in the black and, in addition, provide the French crown with large sums of money at no expense. He proposed a lottery.

Portrait of Joseph Pâris-Duverney, founder of the Military School. Credit: Louis Michel van Loo/Wikimedia Commons

The idea was nothing new. But this brash Venetian brought something that no one else had thought of: extraordinary confidence in the power of probability, an understanding of the law of large numbers, and an insistence that risk would necessarily be part of the venture. He insisted that the lottery be drawn frequently, that large winnings be guaranteed, and that it be held completely under state control. If any of these conditions were rejected, he would have no part of it, and the king would fail to realize massive income for France. He presented his idea to Madame Pompadour (the king’s highly influential mistress), the executive council of the École Militaire, and in the presence of one of the greatest mathematicians of the age, Jean le Rond d’Alembert. From the documented conversations, it appears that the only thing he offered of any novelty was the confidence that if the king lost millions on the first lottery drawing, this would serve as publicity; and if he won, well, he won: “If the king loses a large sum of money at the first drawing, the success of the lottery is assured,” he said. “It is a misfortune to be desired.” When asked why they could not assure that the Crown would win, he dismissed the objection as impossible: anyone who claimed that was a liar and a charlatan. The key to success lay in the acceptance of risk.

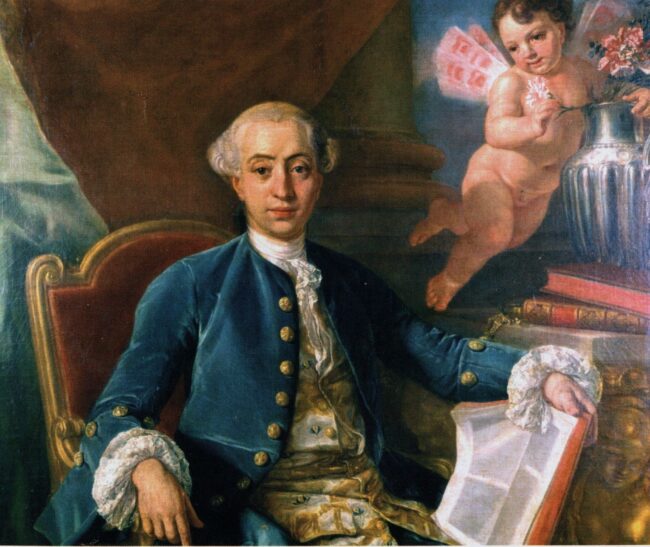

This remarkable fugitive was Giacomo Casanova, the famed seducer — a man whose life was defined by risk.

A portrait of Madame de Pompadour and a dog at the foot of her shoes (portrait by François Boucher). Wikimedia Commons

We know the incredible details of Casanova’s life thanks to the million-word (nearly 4,000 page) manuscript he left behind — a manuscript that survived when the building that housed it was struck directly by an Allied bomb during WWII. It was titled simply Histoire de ma vie, and, when eventually discovered, was purchased by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for about $9,000,000 in 2010. Today, we tend to think of Casanova as a consummate romancer and womanizer whose name is linked to profligacy. That reputation is well-earned. His life was defined by the women he loved, those he cavorted with, and those he abandoned. He reveled in the freedom they granted him and in the freedom they stole from him. Incapable of resisting pleasure, relentlessly pursuing temptation, he was equally incapable of welcoming tranquility —at least until the end.

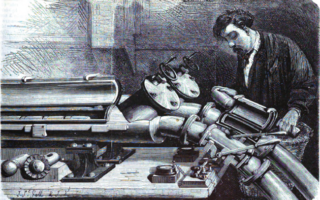

Illustration from Casanovas’s Story of My Flight, 1787. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public domain

But he was much more than a serial romancer and his abilities extended far beyond the boudoir. His biographer calls him “a literary, psychological, and mathematical genius.” One could have said much more of him. He knew Voltaire and thought him rather dull; he documented the Lisbon earthquake; he was arriving to Versailles when the king was stabbed by a would-be assassin (Damiens) and watched the assassin’s execution shortly thereafter; he knew Mozart and evidently contributed something to Don Juan; he knew Pope Benedict XIV and asked his permission to read forbidden books; he knew Rousseau, but was not impressed by him, either; he called on the king of France’s mistress (Madame Pompadour); he translated Homer from the original Greek into Italian.

He was also a con artist, a charlatan, a religious cleric (when he needed to be), an inveterate gambler (he lost everything on several occasions), and a writer — he wrote nearly 20 works. His life reads like a picaresque novel, something between Lazarillo de Tormes and Forrest Gump. His astonishing literary abilities dignified profligacy and raised debauchery to the philosophical heights of epicureanism.

Giacomo Casanova by Francesco Narici. Public domain/ Wikimedia commons

Aside from his autobiography, Casanova’s most lasting contribution is one that continues to enrich France to this day: the lottery. Neither Casanova nor Voltaire could have imagined where the French Lottery would lead. In 2018, France extended Casanova’s lottery to an “annual cultural heritage lottery,” known lovingly as the Loto Du Patrimoine. And we all know how important patrimoine is to the French! The funds go towards restoring important cultural sites such as old churches and monasteries, military fortifications, Roman ruins, aqueducts, and virtually anything that belongs to French heritage.

And so, a man whose name has become a noun — “he is a veritable Casanova!” — famous for his sexual conquests, has, as part of his legacy, the restoration of French cultural sites, thousands of millionaires, and one of the great autobiographies ever written. And probably a few unacknowledged descendants.

NOTE: Laurence Bergreen has written an excellent biography of Casanova titled Casanova: The World of a Seductive Genius.

Lead photo credit : French lottery ticket. Numismatic Bibliomania Society (NBS)/Flickr

More in Casanova, French lottery, Loterie nationale, Lottery, The smart side of Paris, voltaire