Flâneries in Paris: Place de la Nation and the Picpus Cemetery

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 26th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

Emerging from the metro station at Place de la Nation, my first impression was of an enormous roundabout with at least 10 exit roads, a place to make me glad I’ve never tried to drive in Paris. But I knew it would be more intriguing than that, if just because of its colorful previous names: Throne Square and The Square of the Upturned Throne. The massive central statue of Marianne is a reminder that the rejected monarchy was replaced by that key French concept, la République.

It all began in June 1660, when Louis XIV wanted to make a grand entrance into the city as he returned with his new bride, the Spanish Infanta Marie-Thérèse. A throne was duly set up for an impressive ceremony. Louis’ grandiose plans for a triumphal arch to mark the spot were never realized, but there is a different reminder of the square’s royal past at the top of Avenue du Trône, the roading leading east from the square towards Vincennes.

A later king, Louis-Philippe, had statues of two 13th century monarchs, Philippe Auguste and Louis IX, positioned high up over each side of the road. That was in 1841, when the monarchy had been restored, presumably to reimpose the idea of kings as national rulers. So, there they sit surveying “their” territory, although I couldn’t help wondering what they make of the feisty republican Marianne who towers over the square today. She’s having the last word, it would seem.

La Triomphe de la République, as the statue is titled, was erected in 1889 to mark the centenary of the Revolution. Marianne is gazing towards the Place de la Bastille where the Revolution began. I had to look up the significance of the figures surrounding her, which include a blacksmith representing work, children representing the nation’s future, and statues of Justice and Abundance. She was the finishing touch to the square, which had recently been renamed Place de la Nation, another republican gesture in an era which brought in the tricolore and the law stating that the motto liberté, égalité, fraternité should be written on all public buildings.

I began to understand why la Place de la Nation has become a focus for demonstrations, the place from which protest marches often begin. Where else but here would Parisians gather in 1937 to celebrate the first year that May Day, la Fête du Travail in French, was declared a public holiday? In May 2023, the protest march against President Macron’s proposal to raise the retirement age began at Place de la République and ended here. Some protesters clambered up the statue, others held up hastily scribbled banners with dismissive messages like “Manu, tu descends,” informing the president in over-familiar and no uncertain terms that he was “going down.”

Postcard of the monument at Place de la Nation in 1908. Wikimedia commons

But most of all, it’s for its connection to the Revolution that this square is remembered, for it was the site of hundreds of executions during the Reign of Terror. Unrest brewed here in the 1780s because of the toll booths where goods coming into the city could be taxed. They are still there today – the two squat buildings I saw sitting either side of the Avenue du Trône. By June 14th, 1794, when the first executions took place here, the former Place du Trône had been hastily renamed La Place du Trône Renversé – the square of the overturned throne. Robespierre’s terrible vengeance on those he deemed lacking in revolutionary fervor saw 1306 people guillotined here in just a few weeks, more even than in the Place de la Révolution (now the Place de la Concorde).

The execution of the Girondins, 1793. Public domain

I knew that most had been thrown into mass graves in the Picpus Cemetery nearby, so I set off down the Avenue de Picpus to find it. At number 35 on the left, two heavy wooden doors were firmly shut and entry didn’t seem very likely. Two American ladies were about to give up, but a notice on the door suggested we ring the bell and were able to push open the door when a buzzer sounded. Inside the little courtyard, we were greeted by a man who said yes, entry is allowed every day but Sunday, from 2 – 6 pm, and that would be 2 euros each, please. For this is a privately owned cemetery, the only one in Paris. And what a story lies within it.

© Marian Jones

Picpus was originally a monastery – known locally as pique-puce, meaning flea bite, because the monks cured skin diseases – and then the St Augustine’s convent which was confiscated by the revolutionary government in 1792. In June that year a huge pit was dug in the walled garden by revolutionaries looking for somewhere to bury the bodies they had decapitated. They brought them in carts under cover of darkness and when the first pit was full, they dug two more. One young relative followed one of the carts and was later able to tell others where their loved ones had been buried. In the early 1800s, some of them bought the land, determined to keep it as a place of prayer and remembrance.

Victor Marec (1862-1920). “Le cimetière de Picpus et le champ des Martyrs, où furent enterrées les victimes de la Révolution guillotinées à la barrière du Trône.” Huile sur toile. Paris, musée Carnavalet.

I went first into the church, Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix, which stands in the courtyard. Inside, I walked past a set of stunning golden plaques depicting the crucifixion to the end where two massive marble tablets, one each side of the altar, recall the names of every Terror victim buried here. Nobles, yes, about 160 of them, but many others too, in fact far more “ordinary people” than I had realized. All of a sudden, organ music began – an unseen person practicing, I think – creating an appropriate air of respect as I read the names, ages and sometimes occupations listed: Jean Forien, 27, Soldier, J De Bausset, 41, Officer in the King’s Guard, Marguerite Nicole Pierre, 22, market trader. Churchmen, an admiral, a shoemaker, a grocer, a hermit. 1306 names in total. Chilling.

Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix and the entrance of cimetière de Picpus. Photo credit: LPLT / Wikimedia commons

It was a peaceful walk around the back of the church to the cemetery entrance, taking me past a long wall, bordered by a lawn where trees had shed piles of autumn leaves. The families who first bought the land negotiated that they and their descendants would have the right to be buried here, close to the mass graves of their relatives. And so here were many tombs, some surrounded by aging black railings, others set against the back wall where rusty red ivy clambered.

Picpus Cemetery. Photo: Marian Jones

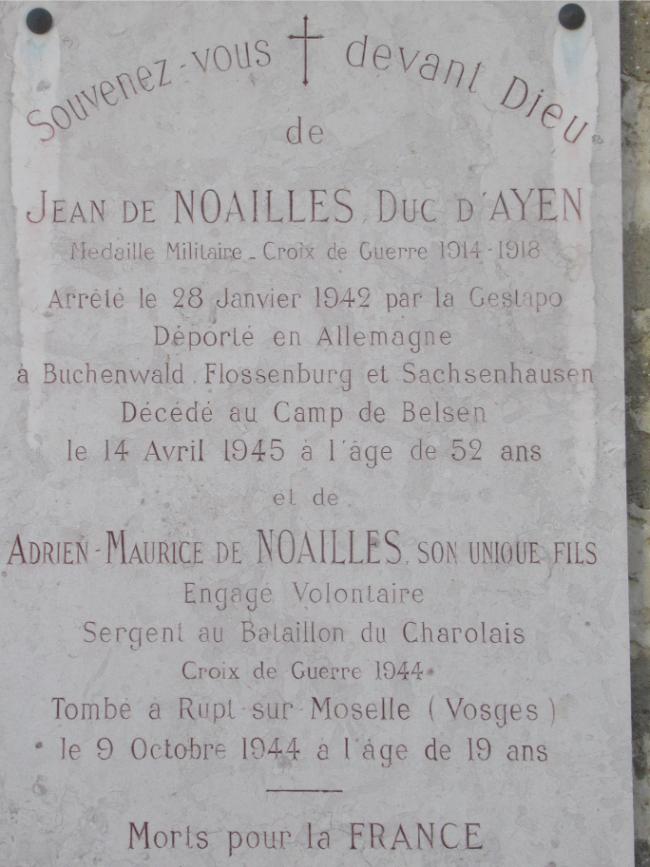

In this section I found names from some of France’s most aristocratic families – De Noailles, La Rochefoucauld, Montmorency, Polignac – and evidence of bravery, sacrifice and persecution in later generations. Jean de Noailles, the Duke of Ayen, won the Croix de Guerre in World War I, but was later deported by the Gestapo and died at the Belsen concentration camp in 1945. With him is buried his only son, Adrien Maurice de Noailles, killed fighting in Alsace in 1944, aged 19. He too had been awarded a Croix de Guerre.

I met the two American ladies in the far right-hand corner, visiting the grave of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, as so many of their compatriots do. To this day, an American flag is planted there, refreshed annually in a ceremony attended by the US Ambassador to France, an eternal reminder of Lafayette’s service fighting under George Washington in the American War of Independence. He was buried here, next to his wife Adrienne de Noailles, whose mother, sister and grandmother had all been victims of the guillotine and lie in the mass grave nearby.

And just past Lafayette’s grave came the wall which keeps the mass graves of Robespierre’s victims undisturbed by visitors, although you can stand at the gate and look through. On the wall, a plaque to the 16 Carmelite nuns, executed one after another, who sang hymns as they were led to the scaffold, a scene hauntingly recreated in Poulenc’s opera Dialogue of the Carmelites. The sound of the guillotine blade is represented in the music as the voices of the nuns drop away, one by one. They are remembered here by name, the Reverend Mother Thérèse de St Augustin and all 15 sisters – Julie-Louise from Évreux, Constance from St Denis – and a sombre Latin inscription: Beati mortui qui in Domino moriuntur: blessed are those who die in the Lord.

Lafayette’s tomb at the Picpus Cemetery is marked by an American flag. Photo: Tangopaso / Wikimedia commons

I returned along the far side of the grounds, passing a back door out to the street through which the carts, with their grisly load of corpses, had been pushed. Then came more reminders of the dark history entombed here: a vault for the Montmorency family, a little cream-colored stone chapel, a plaque marking the spot of the second mass grave, dug in June 1794, where 304 people were tossed without ceremony or prayer. It explains, after “decapitation on the Place du Trône in June, 1794,” they “lie in rest, awaiting the resurrection.”

And so ended my somber walk through a little part of Paris where the very darkest deeds were done well over two centuries ago.

Lead photo credit : Panoramic view of the Place de la Nation. Credit: Francoise de Gandi / Wikimedia commons

More in Flâneries in Paris, Picpus, Place de la Nation, walking tour