The King Who Became a Saint: Louis IX and His Legacy in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

France had 18 kings called Louis, so it is unsurprising that some are more familiar to us than others. We remember Louis XIV, the Sun King who built the Palace of Versailles, and Louis XVI, husband of Marie Antoinette, who was executed in the Revolution. But of all the others, surely the one who ought to be much better known is Louis IX, the only king of France who is also a saint, a man whose legacy is clear in Paris even today, some 750 years after his death. The Île Saint-Louis bears his name and he masterminded one of the city’s best-known buildings, the glorious Sainte-Chapelle.

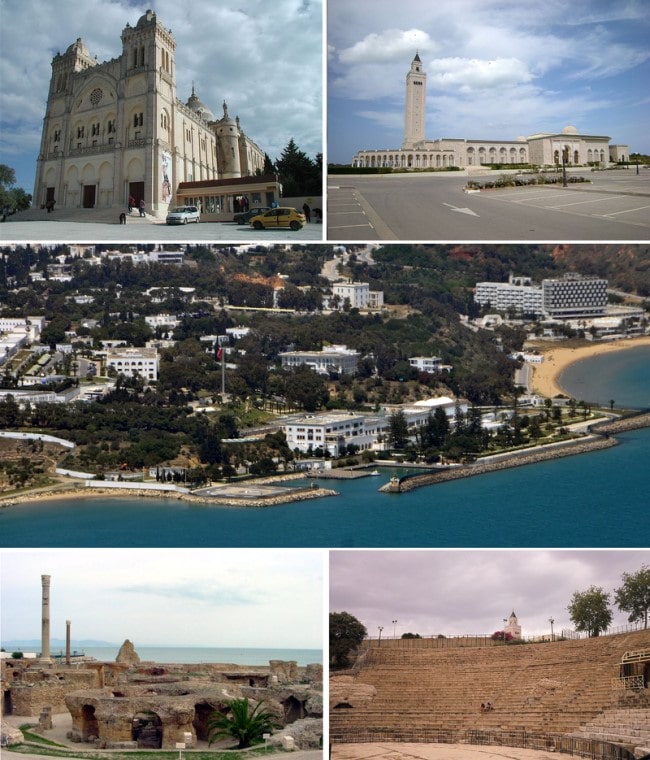

The 12-year-old Louis became king in 1226 and reigned for 46 years, although his mother, the redoubtable Blanche de Castille, acted as regent at first. Louis was canonized only 30 years after his death and his piety was legendary. Said to attend some six masses a day, he wore a hair shirt and regularly invited beggars to dine with him in his palace, feeding them from his own table and eating the leftovers himself. Louis saw himself as God’s lieutenant on earth, and twice went on crusades to, as he saw it, free the Holy Land. These were no light undertakings. He first set out in 1249, taking a hundred ships and 35,000 men, not returning until 1254, after a ransom had been paid to free him from capture. It was on his second crusade to Carthage, in modern-day Tunisia, that he died of dysentery in 1270.

Sainte Chapelle – Upper Chapel, Paris, France (C) Didier B/ Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 2.5

His religious zeal led to the building of the Sainte-Chapelle. Its purpose was two-fold: to serve as a two-storey private chapel, the lower floor being for palace staff, while Louis and his closest family and advisers worshipped upstairs; and to provide a sanctuary for the holy relics which Louis had bought from the Emperor of Constantinople. These reliques de la Passion, said to be from the crucifixion of Christ, included the Crown of Thorns and fragments of the true cross and were stored in a large and ornate silver chest, the Grande Chasse. The chest was melted down during the Revolution, but the relics had been hidden away and were later moved for safe-keeping to Notre Dame.

South facade of Notre-Dame de Paris. (C) sacratomato_hr/ Wikimedia commons/CC BY-SA 2.0

And what a legacy this building is. Must-dos on a trip to Paris surely include both admiring the soaring beauty of its gothic spire from a river trip and staring in wonder at the jeweled beauty of the floor-to-ceiling stained glass windows when you first step inside. Up to 15 meters in height, they are the oldest stained glass windows in the whole of Paris, with over a thousand scenes telling bible stories from Genesis to the Resurrection. Go round the ground floor in a clockwise direction, and the last window you come to depicts Louis himself, dressed as a penitent and carrying the relics back to Paris. One special and calm way to enjoy the building’s beauty is to attend one of the evening concerts held there; for tickets see here.

The apse of the upper chapel (C) Oldmanisold , CC BY-SA 4.0

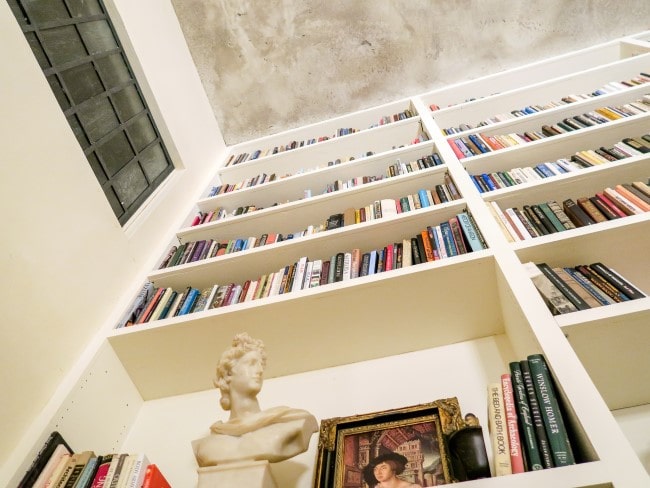

Louis was also a renowned scholar who collected books, especially on theology and philosophy and invited others to read and discuss them. He encouraged his entourage to scholarly pursuits; one of his chaplains, Vincent de Beauvais wrote the first great encyclopedia, Speculum maius, and another chaplain, Robert de Sorbon, with much support from Louis, created the Sorbonne, which soon became the envy of Europe, attracting students from many countries and still today the best-known university in Paris.

Another famous institution founded by Louis is the Archives Nationales. Louis loved to collect old documents, some dating back to the 7th century and he was meticulous about preserving an archive of his own royal acts and judgments. The collection has grown ever since, being formalized at the time of the Revolution and it can be visited today at the National Archives Museum in the Marais district.

Library (C) JOSHUA COLEMAN, Unsplash

Louis certainly had many good qualities as a ruler. He strengthened justice in France, sometimes even hearing disputes from his subjects in person, in his palace or even while sitting under an oak tree in the Bois de Vincennes. He created order, stabilizing the country’s currency, introducing strict laws on counterfeiting and forbidding his officials from gambling or visiting taverns. But he also meted out terrible punishments to heretics, whose rotting bodies were displayed publicly after gruesome executions and he persecuted the Jews without mercy, overseeing the public burning of 12,000 copies of the Talmud and eventually banning Jews from Paris, then from France itself.

When Louis died in Carthage in 1270, he was as famous as it was possible to be in the 13th century. As his body was brought back to France, crowds gathered all along the route, in Italy, in the Alps and through France itself, kneeling in homage as the procession passed. As was common then, only his bones made it back to Paris, it being seen as more hygienic to remove the entrails, then boil the body and remove the flesh. Some of his entrails were buried in Carthage, his heart was placed in a sealed urn and interred in Sicily and the coffin containing his bones was carried all the way to Paris, where funeral rites were performed at Notre-Dame before it was finally laid to rest at the Basilique Saint-Denis.

Montage de photos de la ville de Carthage (C) Issam Barhoumi, CC BY-SA 3.0

Louis IX will surely always be remembered. In the 17th century, over 400 years after his death, the area now known as the Île Saint-Louis was redeveloped and named after him. It was then too that the Church St Louis-en-L’Île was built and still today it houses a statue of him holding his crusader’s sword. But it is next door on the Île de la Cité that his most lasting legacy remains: the stunning Sainte-Chapelle, built in the 1240s and once part of the Palais de la Cité where Louis lived and reigned.

The upper chapel to the west, with the later flamboyant rose window (C) Guilhem Vellut/ Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY 2.0

Lead photo credit : Louis IX receives the crown of thorns and other sacred relics for the Sainte-Chapelle. British Library/ 14th century illustration. Public domain

More in history, Legacy, Louis IX, marie antoinette, Museum

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY