Michèle Barrière: Author of Historical and Culinary Crime Novels

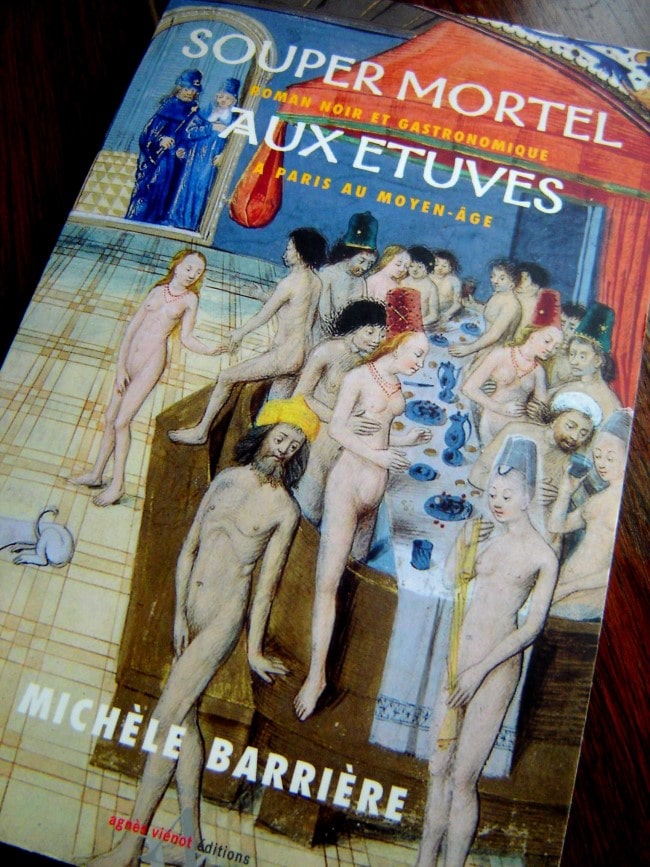

Who in the world has ever read a culinary crime novel set in medieval Paris? I sure hadn’t, that is, until a friend gave me a copy of Michèle Barrière’s Souper Mortel aux Étuves, or Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room.

The novel begins in the year 1393, with a murder at a disreputable steam room establishment in central Paris. The main character of the novel, Constance, must avenge her husband’s murder. To find out whodunnit, she becomes a cook at the steam room, working for the formidable Isabelle la Maquerelle. Belying the lovely rhyme of her name, Isabelle is a feminine version of a maquereau, the French word for the fish mackerel, but also for mac, as in pimp.

Constance counted on everyday run-ins with the steam room’s rough customers, who in typical medieval fashion, would eat with their hands, and possibly the same dagger they used to stab somebody the night before. But what Constance hadn’t bargained for was doing a daily (kitchen) battle with the establishment’s regular chef. During one of their culinary jousts, she meets the famous chef Taillevent.

Michèle Barrière’s first novel, Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room. Photo © Allison Zinder

As a food historian and novelist, Michèle Barrière shows off many authorial talents, and one of them is to weave together fact and fiction. Barrière’s novels trace not only the history and evolution of French kitchens and cuisine, but also French “art of the table” (which includes table manners!) throughout the centuries. Readers also glean historical information on specific people throughout history.

You might recognize from above that Taillevent (real name: Guillaume Tirel) was the alleged author of the period’s most famous cookbook, Le Viandier. But he was also in fact a real working chef to kings Charles V and the VI.

King Charles V loved good food and French books refer to him as a “wise and cultivated” king. During his reign in the 14th century, he managed to channel water from a spring in my local neighborhood of Belleville to one of his residences, the hotel Saint Pol in the Marais. If you’ve been to the Marais, you’ll know that the closest metro station to that area of Paris is called Saint Paul, named for just this residence.

But Charles V was not only a lover of clean water. He was a living patron saint of artists and all sorts of cultivated people, and set up a library containing almost a thousand books in one of the towers of his fortress in the Louvre. This collection would eventually become the royal library, and then the national library, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, or BnF.

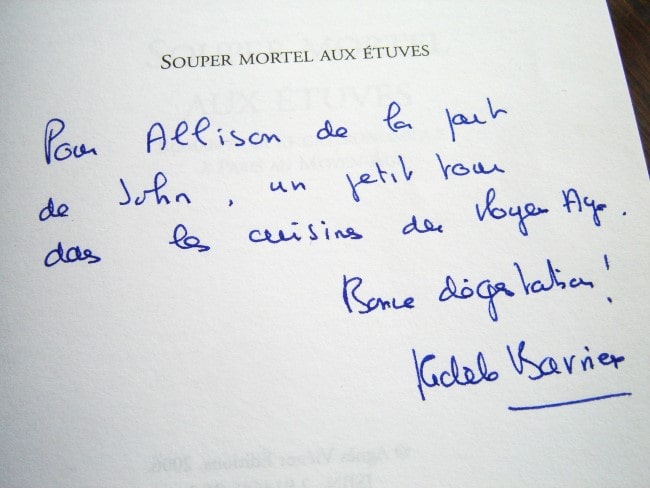

My personal library doesn’t have a thousand books, but it does have a signed copy of Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room. Michèle had inscribed “For Allison, from John: a little spin through the kitchens of the Middle Ages. Happy tasting!” Before the pandemic, when meeting people in cafés was a normal activity, I had the pleasure of interviewing Michèle in person near her home in Montmartre.

“A little spin through the kitchens of the Middle Ages.” Photo © Allison Zinder

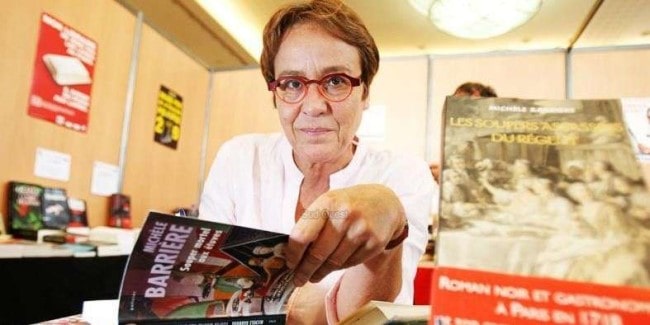

Stepping out of her building dressed in construction-style boots, Michèle held the thick green leash of a beagle, who leaped into the air, barked, and then grabbed the leash with his mouth. I guess he thought he was back in Normandy, where Michèle spends a lot of time in summer, growing her favorite vegetables, and at one point, hosting medieval cooking weekends.

Michèle has a noticeable gap in between her two front teeth, which the French refer to as les dents de bonheur or “lucky teeth.” I consider Madonna and French singer Vanessa Paradis to be fairly serendipitous people. (Or was that just hard work that made them so successful?) In any case, I love this expression: where most people see a cosmetic flaw to be “repaired,” the French consider the tooth gap as lucky!

After meeting, we walked down to the corner of her block, where several locals called out hello from the other side of the street: three youngish, handsome guys crossed to greet Michèle, the neighborhood’s local star. She seems to know everyone in this village-like part of Paris, even inside the café, where the other habitués, or regulars, greet her with a hearty “Salut Michèle!”

When I ask Michèle how she came up with the ideas for the books she writes, her face becomes animated and her language is peppered with all sorts of food expressions (there’s one right there…). She says that the idea for her books had been “macerating” for years, and that she was “nourished by reflection” after spending time at the Drouot auction market where she came across the occasional antique cookbook.

Michèle told me that the idea for all the books came to her in a flash one night, and she immediately set down on paper all the titles of the first series. Published in 2009, Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room was Barrière’s first novel. Since then, she has gone on to publish 14 other books, all in her personally invented category of historical culinary crime novels.

Ten of those stories make up the Savoisy dynasty series, beginning in the late 14th century with Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room and spanning the centuries to one of my favorite eras in French eating: the 1930s. Three-Star Murder takes the reader into the kitchens of the famous Lyonnaise chef Eugénie Brazier.

Three-Star Murder, published in 2016, takes us into the Michelin-starred kitchen of Eugénie Brazier. Photo © Michèle Barrière

According to Michèle Barrière, at this novel’s heart are famous recipes from Lyon, the world capital of gastronomy, such as “chicken with cream and morel sauce, filet of beef Rossini-style (with foie gras), and lobster with brandy and cream,” all specialties of Brazier’s kitchen.

If your mouth is watering, and you’re motivated to cook, Barrière’s novels all have a mini-cookbook at the end. So if you’re willing to search for a few exotic ingredients (especially for the books set in the Middle Ages and Renaissance), you can reproduce faithfully the most famous recipes of each historical period.

Curious – but also reticent – about the medieval recipes I found in Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room, I decided to test a few. I’ll be the first to admit it: medieval dishes aren’t to everyone’s taste. They’re often what we call sucré-salé in French, or sweet and sour, which many French people I’ve met say they don’t like (as they proceed to tuck into a pan-sautéed duck breast with honey sauce, for example).

Medieval dishes are exotic to our tame palates, because they’re full of spices and acidic flavors that came from different types of vinegars. They also featured citrus fruit or verjuice, the frankly sour juice of unripe grapes. Michèle told me she often uses a Swiss vinegar, Kressy. It’s full of herbs, which confer a sweeter flavor to the vinegar, a little closer to the verjus which she prizes for its neither grapey nor vinegary flavor, but something in between, which is just right for cooking.

Sienese Flan, with rose and ground almonds. Recipe from Fatal Dinner at the Steam Room. Photo © Allison Zinder

If you’re used to eating them, as Michèle seems to be, dishes from the Middle Ages are “light, tangy, full of color, and easy and quick to make.” If you don’t eat lots of butter and cream, then medieval recipes are for you: sauces were thickened with ground almonds, bread crumbs, or eggs. Not exactly the Paleo Diet, but who knows: could the Dagger Diet be the next big trend?

The recipe I really enjoyed was a Sienese Flan, a custardy dessert made with ground almonds. It has more than a hint of rose, and I took the liberty of sprinkling the top with some chopped pistachios.

Reading Barrière’s books is sheer entertainment, and as an extra, you have access to a culinary historian’s authentic recipes. But the most rewarding experience is gaining a sense of what her life is like, which she describes here: “Writing historical and culinary crime novels means living between your computer and your stove, your head in ancient texts and your hands in the pastry dough.” Michèle Barrière is lucky indeed.

Lead photo credit : Michèle Barrière (C) Guillaume Bonnaud

More in author, crime, gastronomy, medieval, middle ages, Novel, Reading

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY