The Marquis de Lafayette: A Hero of Two Countries

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

[Editor’s note: Today is Lafayette’s birthday! We recently learned about an important fundraising campaign to restore the Versailles memorial statues of Lafayette and Pershing, and at the same time commemorate America’s entry into World War I. Learn more. Here, correspondent Sue Aran explores Lafayette’s important role in Franco-American history… If you’re in Paris, you can pay your respects at the seldom visited Picpus Cemetery, where an American flag is always flying above Lafayette’s grave.]

Almost five centuries after Vikings explored and briefly settled in small areas on the eastern shores of present-day Canada, the voyages of Christopher Columbus, John Cabot and Giovanni da Verrazzano followed, changing the course of Western history. In 1492, under the auspices of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, Columbus sailed west to find a new trade route to the Far East, landing initially in the Bahamas archipelago. In 1497, John Cabot, under the commission of Henry VII of England, arrived in Newfoundland, and in 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano, while serving France under Francis I, explored the coast of North America, disembarking in what is now New York city. All three kingdoms soon founded colonies respectively named New Spain, New Britain and New France, anxious to draw wealth from the natural resources of the New World. Subsequently, wars were fought and treaties were signed, creating a patchwork of colonies. It was in the British colony of Virginia that George Washington’s grandfather arrived, a member of the landed gentry from Essex, England, in 1631. Five generations later, in 1732, George Washington, the first president of United States, was born. Remarkably, his path would intersect with the Marquis de Lafayette twenty-eight years later during the American Revolutionary War.

Known today simply as Lafayette, the Marquis was born on September 6, 1757 to Michel Louis Christophe Roch Gilbert Paulette du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette, Colonel of the Grenadiers, and his wife, Marie Louise Jolie de La Rivière, at Château de Chavaniac, in the province of Auvergne. Lafayette’s lineage is one of the oldest and most distinguished in all of France. According to legend one ancestor acquired the true Crown of Thorns during the Sixth Crusade, and another Gilbert de Lafayette III, had been a companion-at-arms in Joan of Arc‘s army during the Siege of Orléans in 1429. Lafayette’s mother’s maternal grandfather was the Comte de La Rivière, Commander of the Musketeers of the King (Mousquetaires du Roi), King Louis XV’s personal horse guard.

Lafayette’s birthplace in Chavaniac, Auvergne. Photo: Troye Owens/ Flickr/ Public Domain

Lafayette became Marquis and Lord of Chavaniac after his father died, but the estate went to his mother, who moved to Paris leaving him to be raised in Chavaniac by his paternal grandmother. In 1768, when Lafayette was 11, he was summoned to Paris to live with his mother and grandfather at their apartments in Luxembourg Palace. He attended school at the Collège du Plessis, part of the University of Paris. His grandfather decided that Lafayette would carry on the family martial tradition and enrolled the young boy in a program to train future Musketeers. In May 1771, at age 13, Lafayette was commissioned an officer in the Musketeers with the rank of Sous Lieutenant. At the same time, the wealthy Duc d’Ayen was looking to marry off some of his five daughters. The young Lafayette seemed a good match for his 12-year-old daughter, Marie Adrienne Françoise, and the Duc negotiated a deal; both parties agreed not to speak about the marriage plans for two years, during which time the young spouses-to-be would meet in arranged settings to get to know each other. The deal was more than successful; Lafayette and Marie Adrienne Françoise fell in love, were happily married in 1774, and remained so until her death in 1807. They had four children; Henriette (1776–1778), Anastasie Louise Pauline du Motier (1777–1863), Georges Washington Louis Gilbert du Motier, (1779–1849), and Marie Antoinette Virginie du Motier (1782–1849).

After their marriage Lafayette and his wife settled in the Duc’s house in Versailles. He continued his education, both at the riding school Versailles and at the prestigious Académie de Versailles. He was soon commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Duc’s personal Dragoons. In 1775, Lafayette took part in his unit’s annual training in Metz, where he met the commander of the Army of the East, the Marquis de Ruffec. At dinner one night both men discussed the ongoing revolt against British rule by Britain’s North American colonies. Lafayette became convinced that the American Revolution reflected his own recently acquired Freemason beliefs in liberty, morality and ethics. The following year Louis XVI and his foreign minister agreed that by supplying the American cause with arms and officers, they might restore French influence in North America, a highly desired outcome. On hearing that French officers were being sent to America, Lafayette determined to be among them, and despite his youth, was commissioned as a Major General.

Lafayette as a lieutenant general, in 1791. Portrait by Joseph-Désiré Court. Public Domain.

The plan to send French officers as well as other aid to America came to naught when the British got wind of it and threatened war. Lafayette’s father-in-law and commanding officer, the Duc, thought his son-in-law foolish for wanting to go to North America in the first place, and convinced the King to issue a decree forbidding French officers from serving in America, specifically naming Lafayette. As a result Lafayette went into hiding and, while undercover, learned that the Continental Congress (the governing body through which the American colonial government coordinated resistance to British rule during the first two years of the American Revolution) did not have the money for his voyage, so he purchased a sailing ship, Victoire, with his own funds. He journeyed to Bordeaux where the ship was being readied for the trip, and sent word of his departure to his family. The Victoire raised anchor for the New World on April 20, 1777.

The voyage took two months, during which Lafayette began his study of the English language. He became fluent within a year of his arrival. Making land at North Island near Georgetown, South Carolina, he then traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where the Continental Congress was in session. After offering to serve without pay, he was commissioned by the Congress as Major General on July 31, 1777. Among his advocates was the recently dispatched American envoy to France, Benjamin Franklin, who, by letter, urged the Congress to accommodate the young Frenchman.

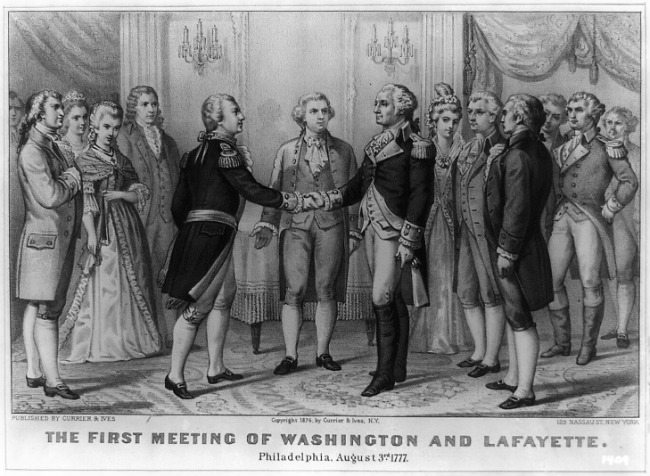

General George Washington, by then commander in chief of the Continental Army, came to Philadelphia to brief the Congress on military affairs. Lafayette met with him at a dinner on August 5, 1777, and the two men reputedly bonded almost immediately. Washington was impressed by Lafayette’s enthusiasm for the cause and quickly made him a member of his staff. Within a few months Washington embraced the young French aristocrat as an adored, all-but-adopted son. Lafayette came to look at Washington as a surrogate father. He served on Washington’s staff for six weeks, and then was given command of his own division.

The Marquis de Lafayette first meets George Washington on 5 August 1777. Currier & Ives. Public domain.

Returning to France in 1778, he collaborated with Benjamin Franklin, in accomplishing an even more important goal– securing full French support for the American cause. Lafayette came back to American shores in 1780 and immediately returned to fighting the British. This time he commanded American forces in Virginia during the decisive campaign against Major General Lord Charles Cornwallis, where he played a key role in entrapping the English general at Yorktown. Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781. Lafayette was then a mere twenty-four years old.

Embraced by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe and John Quincy Adams, the young Lafayette was regarded as the most important Frenchman in the early years of the American Republic. He returned to France that December where he was welcomed on arrival as a hero. A month later he was formally received at Versailles. Upon Thomas Jefferson’s recommendation Lafayette was promoted to Maréchal de Camp, and made a Knight of the Order of Saint Louis. Lafayette worked with Jefferson to establish trade agreements between America and France aimed to reduce the American debt.

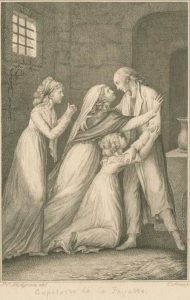

Early 19th century depiction of Lafayette’s prison reunion with his wife and daughters. Henne, Eberhard Siegfried, engraver. Public Domain

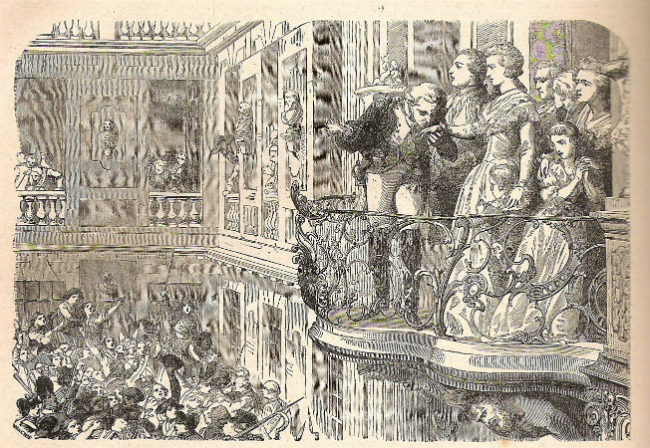

Lafayette remained in France and took an active part in national affairs. Among his many other accomplishments, he was awarded command of the National Guard in Paris the day after the storming of the Bastille, as France teetered on the edge of anarchy. While pushing for republican reforms during the turbulent French Revolution that began in earnest in the summer of 1789, he effectively protected the monarchy. A member of the Assembly of Notables, his was a voice of moderation during the Revolution. During this tumultuous time he wrote the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen”, a document that bore many similarities to the American Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. Forced to flee his homeland when Robespierre seized power, Lafayette was captured by Austrians who had entered into war with France in 1792, and was held for five brutal years while his family remained imprisoned in France. While a prisoner he tried to secure his release using the American citizenship he had been granted previously. In this he was unsuccessful. Then- Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, found a loophole allowing Lafayette to be paid, with interest, for his services as a Major General from 1777 to 1783. An act was rushed through Congress and signed by then-President George Washington. These funds allowed both Lafayette and his family privileges in their respective incarcerations. When Madame Lafayette was released from prison in France, with the help of U.S. Minister to France, James Monroe, she obtained an American passport for her son, George Washington Lafayette, who was then smuggled out of the country and taken to the United States. She and her three daughters journeyed to Vienna for an audience with Emperor Francis, who granted permission for the four women to live with Lafayette while he was in captivity. Having endured harsh solitary confinement, Layfayette was astonished when soldiers opened his prison door to usher in his wife and daughters. The family spent the next two years together in confinement and were finally released in 1797.

Lafayette at the balcony of Versailles with Marie Antoinette. Anonymous. Public Domain.

Through diplomacy, the press, and personal appeals, Lafayette’s sympathizers on both sides of the Atlantic made their influence felt, most importantly on the post-Revolutionary French government. Madame Lafayette was now free to go to Paris, where she secured her husband’s repatriation from the victorious Napoléon Bonaparte, who restored Lafayette’s citizenship. Napoléon then offered Lafayette the prestigious post of Minister to the United States, but was turned down. Perhaps out of spite, Napoléon banned Lafayette from attending memorial services for recently deceased President George Washington in 1799. Soon after Lafayette retired from public life.

In 1804, Napoléon was crowned Emperor of France. The retired Lafayette remained relatively quiet. Following the Louisiana Purchase of that year, then President Jefferson, asked Lafayette if he would be interested in the Governorship of that vast new acquisition, but again Lafayette declined.

During a trip to Auvergne in 1807 Madame Lafayette became ill, suffering from complications stemming from her time in prison. She recovered enough by Christmas Eve to summon her family around her bed and say to her beloved husband “Je suis toute à vous” (I am all yours). She died the next day.

In 1824, President James Monroe and the Congress invited Lafayette to visit the United States in part to celebrate the nation’s upcoming 50th anniversary. Monroe intended to have Lafayette travel on an American warship, but the General felt having such a vessel as transport was undemocratic, and he booked passage on a merchantman. On arrival in New York city Lafayette was greeted by a group of Revolutionary War veterans, who had fought alongside him many years before. New York erupted for four continuous days and nights of celebration. When he departed for what he thought would be a restful trip to Boston, he found instead his route lined with cheering citizens. To the mesmerized onlookers Lafayette had materialized from a distant age, the last leader and hero of the new Nation’s defining moment.

Lafayette and Washington at Mt. Vernon, 1784. Thomas Prichard Rossiter (1818–1871), Louis Rémy Mignot (1831–1870). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public Domain

The visit included an emotional stop at Washington’s grave in Mount Vernon, Virginia, then he journeyed to Monticello where the ailing 81-year old Thomas Jefferson feted his old friend, along with then President James Madison who arrived unexpectedly. Lafayette also dined with the other living founder and former president, 89-year-old John Adams, at his home near Boston. He stayed for the winter of 1824–25, and was there for the climax of the hotly contested 1824 election, in which no presidential candidate was able to secure a majority of the Electoral College, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives. On February 9, 1825, that body selected then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams as President.

In March 1825, Lafayette began a tour of the southern and western United States. He was escorted between cities by the state militia, and he would enter each town through specially constructed arches to be welcomed by local politicians or dignitaries, all eager to be seen with him. There were special events, visits to battlefields and other historic sites, celebratory dinners, and time set aside for the public to meet the legendary hero of the Revolution.

One story told repeatedly was that while he was traveling up the Ohio River by steamboat, Lafayette’s vessel sank from beneath him. He was put in a lifeboat, then taken to the Kentucky shore and rescued by another steamboat. Although it was going the other direction, its captain insisted on turning around and taking Lafayette to Louisville. From there, he went northeast, visiting Niagara Falls, and taking the Erie Canal—considered a modern marvel—to Albany. Returning to Massachusetts in June 1825, he laid the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument after hearing a speech by Daniel Webster. From Bunker Hill, Lafayette took home soil that would, at his death, be sprinkled on his grave.

After Bunker Hill, Lafayette went to Maine and Vermont, having finally visited all twenty-four states then in existence. He celebrated his 68th birthday on September 6th at a White House reception hosted by President John Quincy, and departed the next day for France. Besides the soil to be placed on his grave, he took with him other gifts. Congress had awarded him $200,000 and a large tract of land in Florida, in repayment for his services and donations to the country. The passage back to France was aboard a ship originally called the Susquehanna, renamed the USS Brandywine in honor of the battle in which, years before, Lafayette had shed his blood for the nascent United States.

Lafayette spoke publicly for the last time to the Chamber of Deputies on January 3, 1834. The following month, he collapsed from pneumonia while attending a funeral. He died on May 20, 1834 on 6 rue d’Anjou-Saint-Honoré in Paris (now 8 rue d’Anjou in the 8th arrondissement of Paris) at the age of 76. He was buried next to his wife at the Picpus Cemetery under the soil he brought back from Bunker Hill. In the United States, President Andrew Jackson decreed that Lafayette receive the same memorial honors as those bestowed at Washington’s death: both Houses of Congress were draped in black bunting for thirty days, and members wore mourning badges. Former president John Quincy Adams gave a eulogy that lasted three hours, calling Lafayette, “…high on the list of the pure and disinterested benefactors seeking liberty for all mankind.” According to cultural historian Lloyd Kramer, Lafayette (as well as a later visitor to America, Alexis de Tocqueville) “provided foreign confirmations of the self-image that shaped America’s national identity in the early nineteenth century and that has remained a dominant theme in the national ideology ever since: the belief that America’s Founding Fathers, institutions, and freedom created the most democratic, egalitarian, and prosperous society in the world.”

Pershing saluting the Marquis de Lafayette’s grave in Paris. Bain News Service. Public Domain.

In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sang Lafayette’s praises in a speech delivered to a joint session of Congress: “We the people of this nation have enshrined him in our hearts and today we cherish his memory above that of any citizen of a foreign country. It is as one of our nation’s peerless heroes that we hail him. More than two million American boys… went to France to fight in World War I. Those soldiers and sailors were repaying the debt of gratitude we owe to Lafayette and at the same time they were seeking to preserve those fundamentals of liberty and democracy to which in a previous age he had dedicated his life.”

One of those American soldiers, U.S. Army Colonel Charles E. Stanton, summed up the feelings Roosevelt alluded to on July 4, 1917, three months after American troops joined the Great War. The words came at Lafayette’s grave at the Picpus Cemetery in Paris. At the close of a brief ceremony during which he placed an American flag over Lafayette’s grave, Colonel Stanton, an aide to U.S. General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing, declared: “Lafayette, we are here!”

In 2002, a Congressional Resolution noted acknowledged that, “…Lafayette served the cause without pay—and, in fact, paid the equivalent of more than $200,000 of his own money for the salaries and uniforms and other expenses for his staff and aides and junior officers. He risked his life for the freedom of Americans demonstrating bravery that forever endeared him to the American and secured the help of France to aid the United States’ colonists against Great Britain.”

Lead photo credit : Lafayette (right) and Washington at Valley Forge by John Ward Dunsmore (1907). Public Domain

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY