Americans in Paris: Isadora Duncan, An Icon of Modern Dance

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

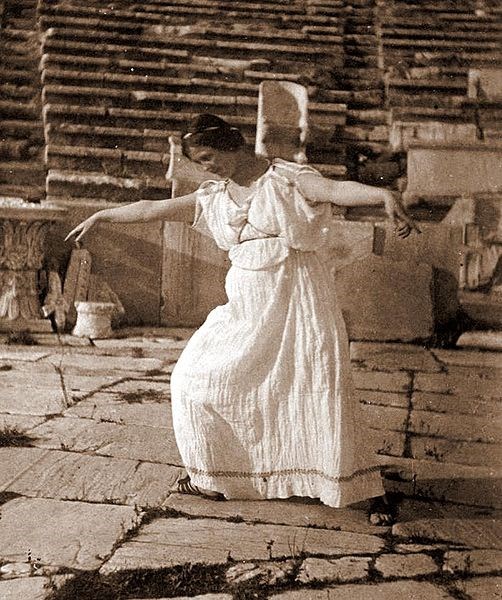

Isadora Duncan at Theatre of Dionysus, Athens 1903 by Raymond Duncan, Online Archive of California

The second installment in a series about famous Americans who lived and died in Paris.

Everyone knows how Isadora Duncan died. Her long silk scarf, caught up in the wheels of a speeding, open topped Amilcar in Nice in 1927, caused her to be flung from the car breaking her neck on impact. (There were other theories that in fact the force of the strangulation would have decapitated her.)

Isadora Duncan’s life however was just as dramatic and singular as her death.

Her dancing, which she always referred to as ‘my art,’ was her way of expressing truth through gesture and movement. She was never, from an early age, to be deflected from this obsession. An obsession that carried her through countries and continents, feted by the rich and famous, artists and writers and poets– she was a favourite of Rodin— but who would never compromise her form of dancing for any amount of money, despite often being in dire need.

Isadora Duncan as the first fairy in Midsummer night’s Dream, 1896

Isadora Duncan was no stranger to poverty. Born in San Francisco on May 26th, 1877, Isadora was the youngest of four children (siblings were August, Raymond and Elizabeth). Her father, Joseph Charles Duncan, was a banker and engineer who fell from grace soon after Isadora’s birth after being exposed in illegal banking practices. Isadora’s mother, Mary Isadora Duncan, divorced her husband and the family now in distressed straits, moved to Oakland.

Whilst Isadora’s mother gave piano lessons and sewed, Isadora began teaching young children in the neighbourhood to dance. She was six years old. By 12 years old, she was already a feminist, anti marriage and pro having children– when and how it suited women– outside wedlock. The family, still being poor, moved often, and Isadora by her own account being the most courageous would inveigle the butcher or baker to extend credit. She gave up formal school at 10, but read incessantly: Thackeray, Dickens and Shakespeare, Greek Classics as well as trashy novels. The Greek classics would influence Duncan’s dancing for the rest of her life.

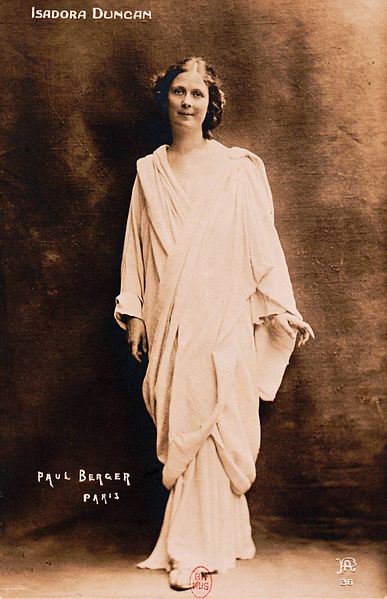

Duncan with her trademark Greek tunic , by Paul Berger

One of the most extraordinary facets of Duncan’s personality was not only her unwavering self belief but her ability to sweep others along with it, to bend them to her will. Disillusioned with her progress in San Francisco, she ‘harangued’ her mother to accompany her to Chicago whilst her sister and two brothers stayed in San Francisco until she made her fortune and sent for them.

Already dancing in a plain white Greek tunic which was to become her trademark, theater managers in Chicago were less than impressed with Duncan’s free form style and informed her that her singular vision of dance was incompatible to dance and theater companies.

After pawning her grandmother’s jewelry, their money finally ran out and Isdaora and her mother were put out on the street. Only by selling her lace collar could Isadora and her mother afford a room for a week, eating only a box of tomatoes as sustenance.

Undeterred by this episode, the family were still persuaded to move to New York on the promise of a part for Isadora in a pantomime in Daly’s theater. Once more during the six weeks of rehearsals the family had no money and were forced to live in two unfurnished rooms, skipping lunch and unable to afford tram fare.

Finally after two years in Daly’s company, Isadora could take no more and left; it was only a chance encounter with Ethelbert Nevin, the composer, that changed the Duncan’s fortunes. Isadora, entranced by his music, “Narcissus”, “Ophelia” and “Water-Nymphs,” demonstrated her dance interpretations of his compositions.

Carried away by Duncan’s dancing, Nevin arranged a concert for her in the Music Room of Carnegie Hall. The concert was a great success and engagements followed in the drawing rooms of rich New York society, including Mrs Astor, whose guests included the Vanderbilts, Belmonts and Harry Lehr.

Public domain

It wasn’t long before Isadora became dissatisfied dancing in front of an audience she believed did not appreciate her ‘art’ and lured by the idea of all the famous writers and painters of London, decided that, yet again, penniless, London was her next stop.

Once more, with her inimitable ‘courage’, or some would say, brass neck, Isadora canvassed millionaire’s wives in New York, begging and borrowing enough money ($300) to pay for the family to go cattle-boat to London. Duncan says in her autobiography that in the amazement and delight of being in London and their sightseeing at the British Museum, Westminster Abbey, Kew Gardens, etc, they simply ‘forgot’ about their limited resources. The inevitable followed; they were thrown out of their boarding house and lived on the streets for three days before Isadora blagged her way into one of the finest hotels in London, stayed two nights and then sneaked out without paying.

As in New York, Isadora danced in private salons, helped by meeting Mrs Patrick Campbell who had seen Isadora and her brother Raymond dancing in Kensington Square Gardens. Soon she was introduced to Charles Halle who was a director of the New Gallery which had a central court and fountain where Isadora danced in front of an illustrious audience. Isadora’s fame grew, newspapers loved her, she was presented to the Prince of Wales and her financial status improved enough to rent a small house in Kensington Square. Isadora’s sister Elizabeth, with the promise of work in America, had returned to New York and Raymond, her brother, restless in London, left for Paris.

Isadora and her mother soon followed and they rented a studio in Rue de la Gaîté for 50 francs a month. Raymond and Isadora rose at 5am and began the day dancing in the Luxembourg Gardens before walking miles around Paris and spending hours in the Louvre.

Although Isadora’s fame was spreading through Paris, her financial situation was always precarious and the arrival of Loie Fuller to her studio was much more than fortuitous.

Loie Fuller was an American dancer, famous for her sinuous Serpentine Dance, who like Duncan did not feel appreciated in America and encouraged by her warm reception in Paris became a regular dancer at the Folies Bergère. Fuller became the embodiment of the Art Nouveau movement, Toulouse Lautrec painted her, Rodin and Marie Curie numbered but a few of her admirers.

(La Danseuse, a film by Stephanie di Gusto, charting the lives of Loie Fuller, played by Soko, and Isadore Duncan, played by Lily-Rose Depp, the daughter of Vanessa Paradis and Johnny Depp, debuted at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival.)

Lois Fuller invited Duncan to join her in Berlin and tour Europe with her dance troupe. Duncan proved a huge success every place she appeared and finally she had a sum of money in her bank that she believed was ‘inexhaustible’.

There followed perhaps the strangest interlude in Duncan’s life. With the family all back together, they traveled to Greece and bought a plot of barren land outside Hymettus, mainly because it was on the same level as the Acropolis. By then they were all garbed in ancient Greek attire, tunics and sandals with fillets around their hair, to the incomprehension of the locals. Raymond designed a temple and when the first cornerstone was laid, they engaged a priest to offer a black cock as a sacrifice, spilling its blood on the cornerstone and chanting incantations. The intention was never to leave Greece and their temple and to dance there forever.

The whole enterprise was an unmitigated disaster financially and although Duncan avowed this year in Greece was her best ever, the temple was never to be finished and had quite easily depleted her ‘inexhaustible’ bank account, and Duncan was back on the road again touring Europe and Russia.

In Berlin she met Gordon Craig, the son of Ellen Terry, and soon became pregnant, giving birth to a daughter, Deirdre.

Duncan with her two children, 1911 by Otto Wegener

Returning to Paris and her longed-for dream of her own dancing school, Duncan took two large apartments in the Rue Danton. Money problems still plagued Duncan and half in jest she longed for a millionaire. Paris Singer (son of Isaac Singer, the sewing machine magnate) appeared almost on cue. Yachts, rich living and a son she named Patrick were all short lived. Her relationship with Singer ended but a far greater tragedy was to befall her.

Her two children, with their nurse returning from Neuilly to Versailles, were in their car when it ran out of control and into the Seine. Both children drowned.

It is doubtful whether Duncan ever recovered from this, and desperate for another child, begged Romano Romelli an Italian sculptor to give her a child. She did become pregnant but the child, a son, died shortly afterwards.

In 1921, Duncan went to Moscow and married Sergei Yesenin, 18 years younger than her and a renowned poet. The marriage lasted barely a year and after accompanying Duncan on tour of Europe and the US, Yesenin left her. In 1925, he was found dead in St Petersberg, an apparent suicide. Duncan did however take Soviet citizenship and had a fervent belief in communism.

Duncan with Sergej Esenin, 1923

In later years, Duncan, now plumper and with the inevitable money problems, became notorious for her scandalous affairs, financial situation and public drunkenness.

After her cremation in Nice, her ashes were transported to Paris and placed next to her children in the Columbarium in Père-Lachaise cemetery.

A plaque with the simple inscription–

Isadora Duncan. 1877-1927

Ecole du Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris

— marks the final resting place of this extraordinary woman.

Lead photo credit : Isadora Duncan at Theatre of Dionysus, Athens 1903 by Raymond Duncan, Online Archive of California

More in Americans in paris