Paris in the 1920s: The Tale of the Notorious Kiki de Montparnasse

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In the ‘Années Folles’ of 1920s Paris, particularly in Montmartre and Montparnasse, uninhibited behavior was unlikely to raise an eyebrow. It was an era unsurpassed by its artistic and literary output, when bohemia lay its restless head on the pillows of the 14th and the 18th arrondissements and decided to stay.

Neither quartiers were new to the bohemian life of artists and writers, nor to the excesses of alcohol and promiscuous living. Montparnasse and Montmartre in the 19th century were the epicenters of avant-garde artists, cabaret clubs and Bals Musettes, Can Can dancers, cheap absinthe, and loose living, but there was something unique in the atmosphere following the end of the brutalities of the First World War that made behavior in the 1920s more outrageous and licentious than ever before.

And there was no-one more outrageous than Kiki de Montparnasse.

Born Alice Ernestine Prin in Châtillon-sur-Seine in 1901, she was the third daughter of Marie Ernestine Prin. (Marie’s first two daughters had died, one stillborn in 1898, and the second, Maximillienne Alice, at the age of four months.) Alice’s father was presumed to be a charcoal merchant, Maxime Legros.

When Alice’s mother left Châtillon-sur-Seine to work in Paris, she was brought up in extreme poverty by her grandmother, along with various cousins who had either been orphaned or abandoned. Alice had felt the loss of her mother keenly and although she adored her grandmother who had done her best to raise Alice with love and affection, Alice had already begun to sing in bistros with her godfather, who as a bootlegger, was a less than upright role model. In consequence, Alice had acquired a taste for alcohol before she was even 12 years old.

In 1913, Alice’s mother brought her to Paris where they lived in the 15th arrondissement in Rue Dulac. After a scant year of schooling in the Rue de Vaugirard, Alice began work at a factory repairing soldiers shoes. Two years later when Alice was fifteen, her mother fell in love with Noel Deleccoeuillerie, a soldier, eleven years her junior, who had returned to Paris after being wounded at the Front. They would eventually marry in 1918, but when Noel moved in to their lodgings in 1917, three was definitely a crowd, and Marie found Alice a job in a bakery where she lived.

The hours were long and hard in the bakery, the wages poor, and Alice– after months of arduous labour– finally had had enough and left. Her mother, unable or unwilling to help her daughter, left her with little options, and Alice agreed to model naked for the sculptor Ronchin. When Alice’s mother discovered she was posing naked, she promptly and furiously disowned her.

Alice, at sixteen years old, was suddenly homeless and on the streets. This was a not uncommon situation for poor young girls at the time, and like many before her, Alice was forced to live on her wits, to survive in any way that she could. For a young, attractive female, surviving always meant a sometimes unwanted, but necessary, dependence on men.

Invariably, artists’ models were classed as no more than common prostitutes, and it is true that it was rare for a model not to sleep with whichever artist or sculptor she was modeling for. Alice was no exception. (One of the only models recorded to have had a platonic relationship with an artist was Lydia Delectorskaya, who was Matisse’s model until he died.) But Alice was pragmatic about her situation; she enjoyed sex, was uninhibited and had immersed herself in the bohemian norms and the milieu of Montparnasse with gusto and undiluted enthusiasm.

She proved very quickly to be a popular model, and the painter Soutine soon introduced her to Modigliani and Utrillo, who both painted her at this early stage in her career. It was however, the Polish artist, Maurice Mendjisky, who Alice fell in love and lived with until 1922. It was also Mendjisky who renamed her Kiki.

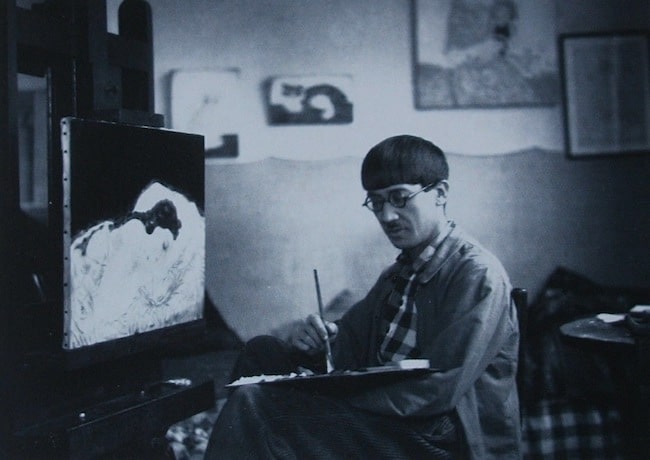

By now a fixture in Montparnasse in the bars and the clubs, Kiki was spotted by the painter Kisling in La Rotonde and became his model throughout the 1920s. A more important and life long friendship was formed with the Japanese painter Foujita. Tsuguharu Foujita had arrived in Montparnasse in 1913 and with his black hair cut in a short, uncompromising fringe, heavy glasses, sandals and tunic, he cut an unforgettable figure. Picasso had introduced him to Max Jacob and Apollinaire in 1914 and he was immediately entranced by Isadora Duncan, and like Isadora, and her brother Raymond, Foujita would dance in the woods in a toga. But it was Kiki who was his favorite model and his painting of her, ‘Nu couche a la toile‘, marked the beginning of his real success as an artist. ‘Nu Couche a la toile‘ was exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Le Grand Palais in 1922 and was sold for 8,000 francs. Foujita shared some of the proceeds with Kiki.

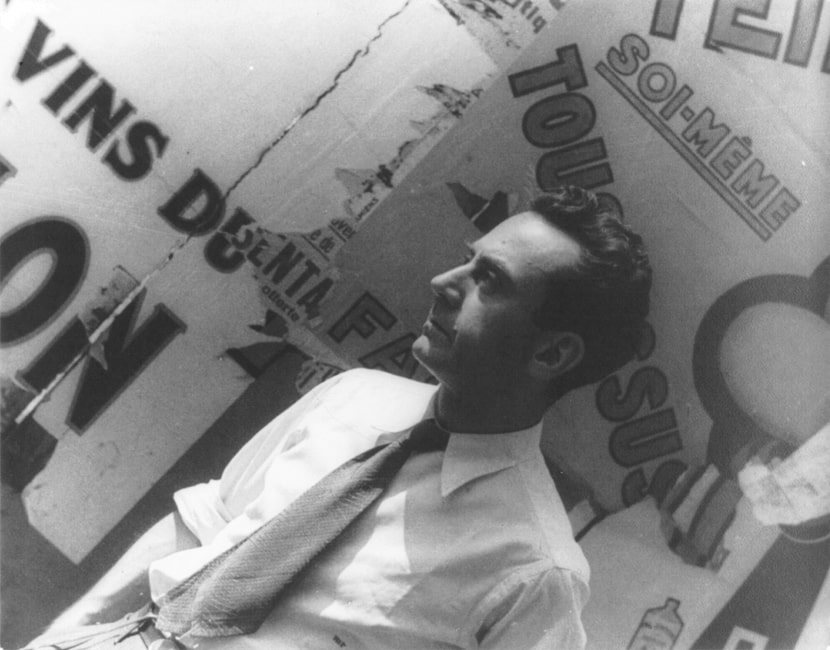

In 1921, Mendjisky tried to persuade Kiki to accompany him to the Côte d’Azur but Kiki was reluctant to leave Montparnasse and so Mendjisky left without her. It proved to be a fortuitous decision. Shortly afterwards, Kiki met the American photographer and painter Man Ray, and swiftly became his muse, model and mistress, moving into the Hotel des Ecoles on the Rue Delambre with him.

Man Ray (Emmanuel Radnitzky) was an extraordinarily talented artist, more than proficient in sculpting, painting, collage and excelling in innovative photography. He had met Marcel Duchamp in America in 1913. Duchamp had influenced Man Ray in cubism and dadaism, and it was Duchamp who had met Man Ray off the train in the Gare Saint-Lazare in 1921, and Duchamps who introduced Man Ray to his dadaist circle of friends which included Breton, Eluard, Ernst and Soupault.

Man Ray and Kiki de Montparnasse together were a marriage (and sometimes a hell) made in heaven, and brought Kiki to an even greater fame. Over seven years, Man Ray photographed Kiki in every pose, from close up to pornographic, and introduced her in his short films. But it is Many Ray’s surrealist photographs of Kiki, Le Violin d’Ingres and Noir et Blanche, that remain iconic to this day.

It was perhaps Kiki’s success in the dadaist films that had persuaded her that she could make it in Hollywood. Man Ray refused to leave Paris and so Kiki– accompanied by two young Americans (one of which was her lover, Mike)– sailed to America to launch her career at the Famous Player’s Studios in 1923. Kiki’s English was rudimentary at most, and the studios weren’t interested in her. Neither was Mike, who left her there, penniless. It was Man Ray who sent her the money to return to Paris, and she returned to live with him for the next six years.

Despite her failure in Hollywood, 1923 turned out to be an auspicious year for Kiki and the beginnings of a career which would culminate in her notoriety. At the corner of rue Campagne-Première and the Boulevard du Montparnasse, a new nightclub, Le Jockey, opened. It was an immediate success attracting anyone who was anyone: artists, writers, actors and night owls. It was customary for customers to do a party piece, and one night, Kiki, well oiled, danced on the table and sang a very bawdy song. It was already obvious that Kiki had dispensed with wearing knickers; later after she’d been taught the Can Can by her friend, Treize, there was never any doubt. Whether her voice or lack of underwear was the attraction is anyone’s guess, but Kiki became the number one attraction in Le Jockey with her friend, Trieze, passing around the hat to an appreciative audience.

Kiki continued to appear in avant-garde films, including a feature length film, La Galerie des monstres, which premiered at the Artistic Cinema on Rue du Douai, and Ballet Mechanique by Fernand Leger and Dudley Murphy.

Montparnasse was overtaking Montmartre for hedonistic living and in 1924, an American Louis Wilson, with his Dutch wife Yopi, bought Le Dingo bar in Rue Delambre. It was an immediate success; Hemingway met Fitzgerald there, James Baldwin was a frequent visitor and of course Kiki was a regular. It is said that she especially liked the company of American sailors who had made it their favorite haunt in Paris. It was a penchant that would get her into serious trouble the following year in Villefranche-sur-Mer.

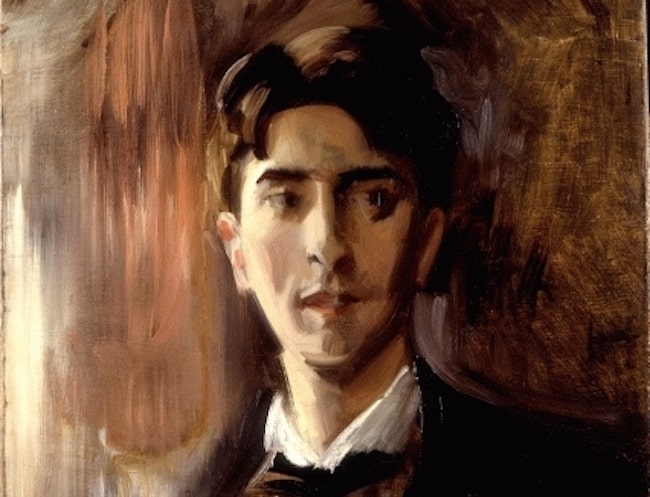

Portrait of Jean Cocteau by Federico de Madrazo y Ochoa, ca. 1910-1912. Photo: Federico de Madrazo y Ochoa, Wikipedia, public domain

Kiki had been friends with Jean Cocteau for several years and Kiki’s introduction to opium has been attributed to him. As with alcohol, Kiki did not limit herself to the amount of opium she used and both demons dragged on her coat tails for the rest of her life. It was on Cocteau’s advice that Kiki moved into the Welcome Hotel in Villefranche-sur-Mer, a favorite of American sailors from warships using the deep water port. Kiki was a huge hit with the sailors, to the annoyance of the many prostitutes plying their trade in the bars around the port. Following a brawl in the Sprintz bar in which Kiki was involved, she was arrested as a streetwalker and unceremoniously thrown in jail. Letters of support were sent, strings pulled and Man Ray appeared as a character witness at her trial. Kiki was spared any more jail time, and sensibly left Villefranche-sur-Mer on the next train.

As well as her outrageous Cabaret appearances, Kiki had begun to paint and write her memoirs.

Her colorful, figurative naive paintings had their first, private viewing in Au Sacre du Printemps at 5 Rue du Cherche-midi. Robert Desnos wrote the text for the catalogue, and most of Kiki’s paintings were sold the first night. Her notoriety could only have helped sales.

Man Ray continued to photograph Kiki, whose lifestyle had neither faltered nor slowed down. The opening night of La Coupole at the end of 1927 saw 1200 bottles of champagne drunk. Kiki was in the crowd to help the consumption rate. Once more at the opening of Au Bal Negre, in 1929, the champagne flowed and Kiki danced the Can Can all night, not content to entertain the crowd without underwear, Kiki’s breasts were exposed as the straps of her flimsy camisole slipped down her arms.

In the same year the first chapters of Kiki’s memoirs were published, written and illustrated by Kiki’s next lover, Henri Broca. Hemingway had promised to write the forward to her memoirs when the English version came out. When she met the singer Jean Blanc, they decided to team up and appeared at the newly opened Boeuf sur le Toit on the Rue de Penthièvre.

By now, Kiki was using cocaine; she had never stopped drinking heavily, and she continued to party, appear in cabaret, write her memoirs and paint. Her health, and her figure, were suffering the years of unabated abuse and her weight had soared to eighty kilos. In an attempt to slim down, she had cut down on her alcohol intake; unfortunately, this had made her dependence on cocaine even more acute.

Her affair with Man Ray was over. Ray had found a new lover, Lee Miller. Ray had made the mistake of telling Kiki in a cafe. Kiki had thrown every plate she could get her hands on at him as he fled. She moved in with Broca, but his mental health was fragile, and he was hospitalized. On his release, he attempted to resume life in Montparnasse, but it was simply too much and he returned to Bordeaux where he died in 1935.

But Kiki was made of stronger stuff than Broca and for the next ten years her multi-faceted career continued to flourish. She triumphed in her signature bawdy cabaret in Berlin, starred in a full length talking movie, Le Capitaine Jaune, and fell in love with Andre Laroque, an accordionist and an unlikely tax inspector, and the two appear together in the Cabaret des Fleurs in Montparnasse. Laroque remained a faithful companion despite Kiki falling madly in love with Margot Vega, a twenty two year old dancer, in 1935.

It was only a matter of time before Kiki opened her own cabaret club, Babel, in 1937. By all accounts the club was chaotic with a junkie pianist added to the mix. Kiki’s management of the club was short lived, although singer Charles Trenet debuted there.

Despite war looming, Kiki recorded her first double sided record, Les Marins de Groix, and Le Retour du marin. (Kiki’s love of sailors had never abated.) Two more records followed, but once more, Kiki’s cocaine addiction was to lead to her arrest for possession of drugs and as was the custom of the times, she was locked up for two weeks in the Salpêtrière mental hospital.

In 1942, the Jockey Club reopened and for a short time in Nazi-held Paris, Kiki returned to sing.

It was not to last and Kiki with a new, and violent, lover, left Paris for the comparative safety of the countryside near Chinon.

The ever faithful, Dede, took her in on her return to Paris in 1945 and she went back to work in Le Boeuf sur le Toit. But Kiki was now in her forties, beset with alcohol and cocaine addictions, and yet again she was arrested for forged prescriptions and spent a month in detention.

There was now only one way to go, a slow, but inexorable, downward slide, where Kiki was reduced to singing in a piano bar in the Rue Vavin and passing around the hat after her performance.

Man Ray, who had left Paris at the beginning of the war and had returned to America, had not seen Kiki from that time, and in 1951, on his return to Paris, where he lived until he died, had been shocked by the transformation of his favorite, muse, model and lover. Kiki de Montparnasse had lost her voice, bloated by dropsy, alcohol and drugs– living on the generosity of old friends.

On the 23rd March, Kiki de Montparnasse died. She was buried with little ceremony in the Thiais cemetery. La Reine de Montparnasse was no more.

When I was writing this article, I came across an American lingerie company called Kiki de Montparnasse. A lace detailed thong cost over $1,000. How the Queen of Montparnasse, who made her name for wearing no underwear, would have laughed.

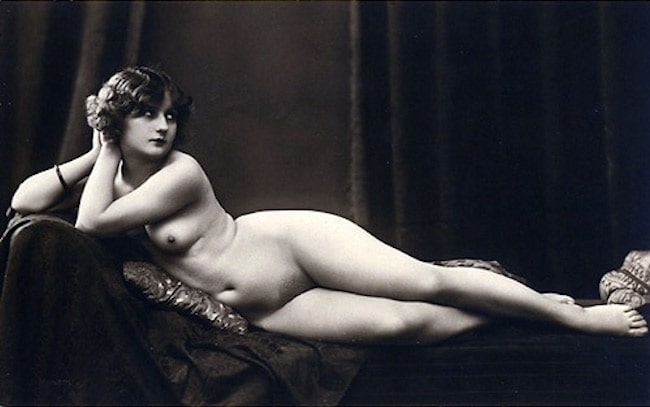

Lead photo credit : Postcard, Alice Prin, c.1920-30. Photo: Julian Mandel, Wikipedia, public domain

More in Kiki de Montparnasse, Man Ray, Montparnasse

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY