Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon: From Montmartre to MOMA

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Pablo Picasso’s infamous painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was born in Paris during the spring-summer of 1907, deep in the bowels of a ramshackle former ballroom turned into a piano factory that became about 20 living spaces and studios for artists, poets, and other bohemian characters. These five strange depictions of female personages launched a myriad of responses from various art historians and journalists over the last century, like flies to honey. Why is this?

Do these hideous harridans exude a magical magnetism like the Sirens in Homer’s Odyssey? I think so. There must be something kinky in all this Picassoesque perversity. Why else would a painting that initially provoked shocked silence now generate the lion’s share of Picasso publications?

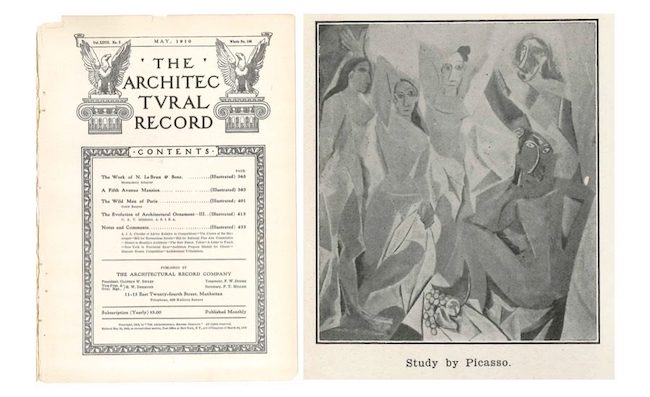

Gelett Burgess, “The Wild Men in Art,” (C) Architectural Record, May 1910 (written in 1908)

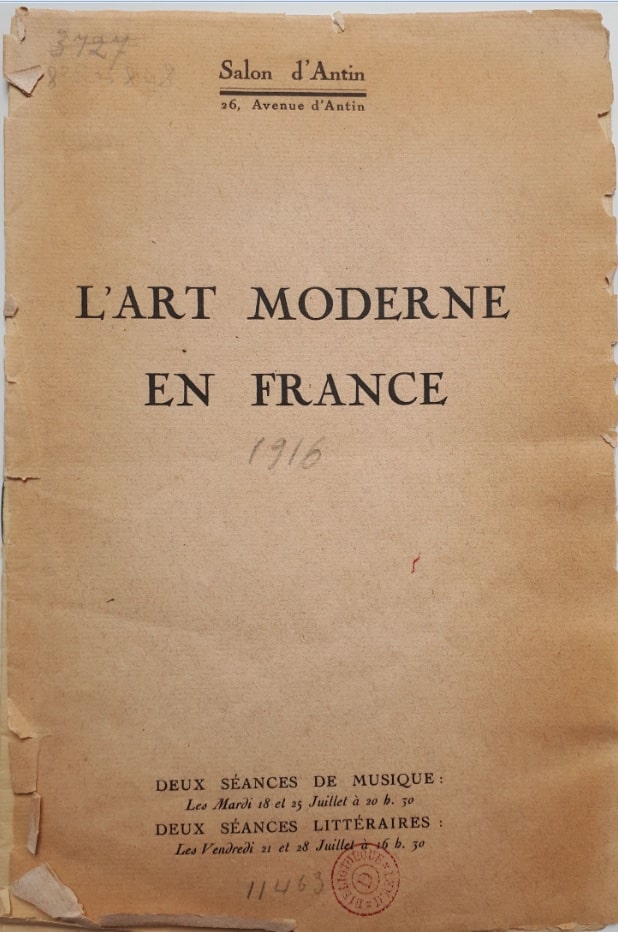

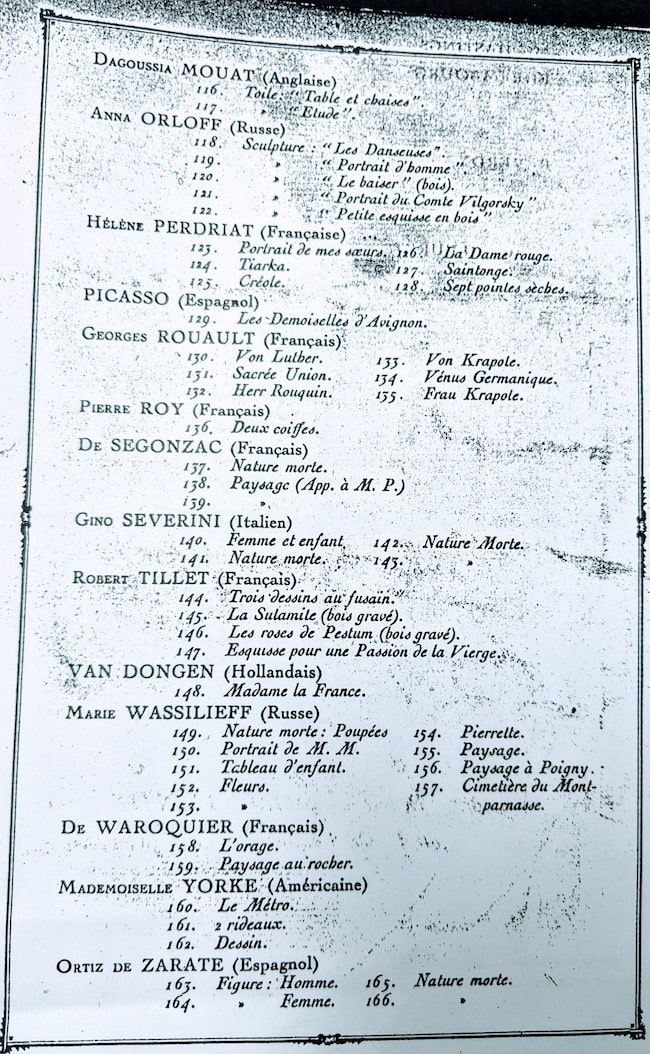

These five lurid ladies became Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies from Avignon) nine years after their birth for a July 1916 exhibition called L’Art Moderne en France. It was the first time Les Demoiselles d’Avignon appeared in public, selected by the curator, poet/critic André Salmon, who had already introduced the painting in his first book on art, La Jeune Peinture française (Young French Painting), published in 1912.

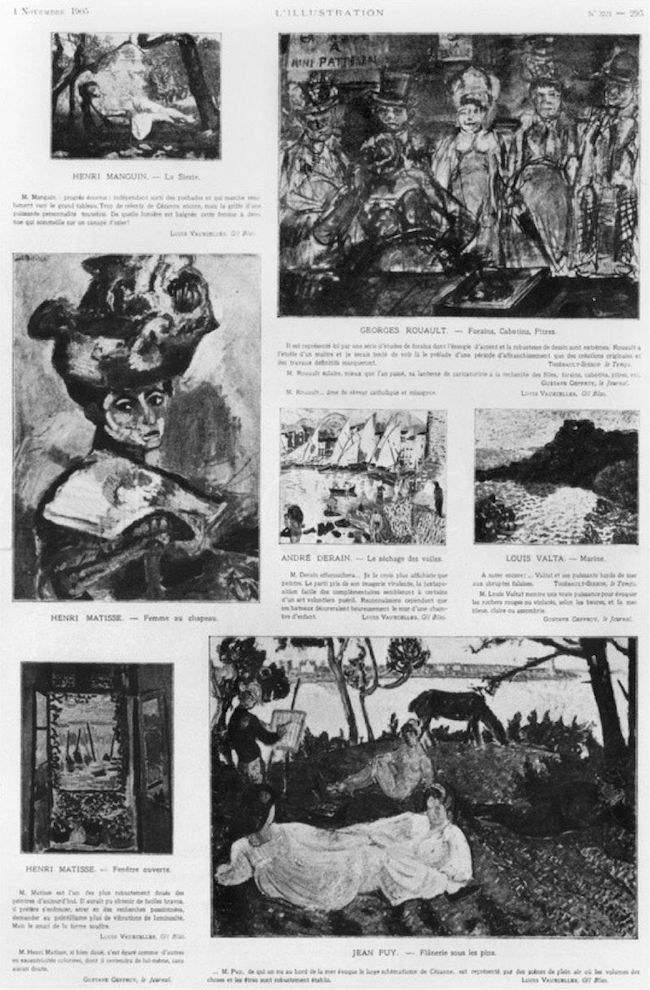

The American public already had access to the image in a black and white reproduction, published in an article called “The Wild Men of Paris,” in Architectural Record, May 1910, two years prior to Salmon’s historic assertion that Cubism began with Picasso’s still hidden “philosophical brothel.” Contextualized among the Fauves (Wild Beasts), whose aggressive work dominated the Salon d’Automne and Salon des Indépendants exhibitions in 1905 and 1906, the American writer Gelett Burgess chose the title Study, indicating that the work had not reached completion.

Salmon’s title considers more pressing problems, as he navigated the contemporary guidelines for public decency. The word “bordel” (brothel) could not appear in print. Picasso claimed he always hated the title. But did he change it? No, he did not.

Salmon, L’Art Moderne En France 1916 cover photograph (C) L’Art Moderne En France

Salmon, L’Art Moderne En France 1916 page with Demoiselles cropped (C) L’Art Moderne En France

The 1916 title Les Demoiselles d’Avignon reminds us of a time when sexually explicit language was censored. World War I had been raging since August 1914. The Paris art scene thinned out as artists, critics and writers joined the French army in the trenches. Salmon’s “Modern Art in France” brought together artists who remained in Paris or had returned from the front (the curator among them). Under the circumstances mainly immigrants and French women participated in this ambitious assortment of 166 works of art. The title for Picasso’s one contribution to the exhibition served as a mask to hint at, but not explicitly say, that this scene takes place in a house of ill-repute, which Salmon knew of through Picasso. Spanish art historian Josef Palau i Fabre verified that a particular brothel at 44 Carrer Avinyó in Barcelona served as Picasso’s model, based on interviews with the artist in 1950. These interviews are stored in the Fundació Palau de Caldes d’Estrac in Barcelona with other material for an unrealized book on Picasso and the Demoiselles.

In 1988, the late art historian William Rubin wrote in his catalogue essay for the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon exhibition at the Musée Picasso in Paris that the name Avignon signified licentious behavior. He deduced that Salmon trusted Picasso and their closest friends would catch the drift. For this exclusive “gang” clever wordplay was all that mattered. If people had to wrestle with it and argue about its real meaning, all the better. The ruse flaunted their typical ribald humor and obfuscations. Tortured guesses or ignorant misunderstandings would fall deliciously into their trap.

Suzanne Preston Blier, Demoiselles book cover (C) Suzanne Preston Blier

The latest casualty reached the bookstores during the winter of 2020 right before the Covid-19 lockdown, Picasso’s Demoiselles: The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece, written by Suzanne Preston Blier, Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University (Duke University Press, 2019). Over the course of le confinement, I tried to plow through the book in order to deliver an objective review. However, one glaring mistake in the preface which attributes a well-known Salmon quote from La Jeune Peinture française to brilliant Picasso expert Hélène Seckel-Klein unnerved me from the get-go. Other errors compounded my lack of confidence in the writer’s sufficient grasp of the Demoiselles literature, generously available in the bibliography.

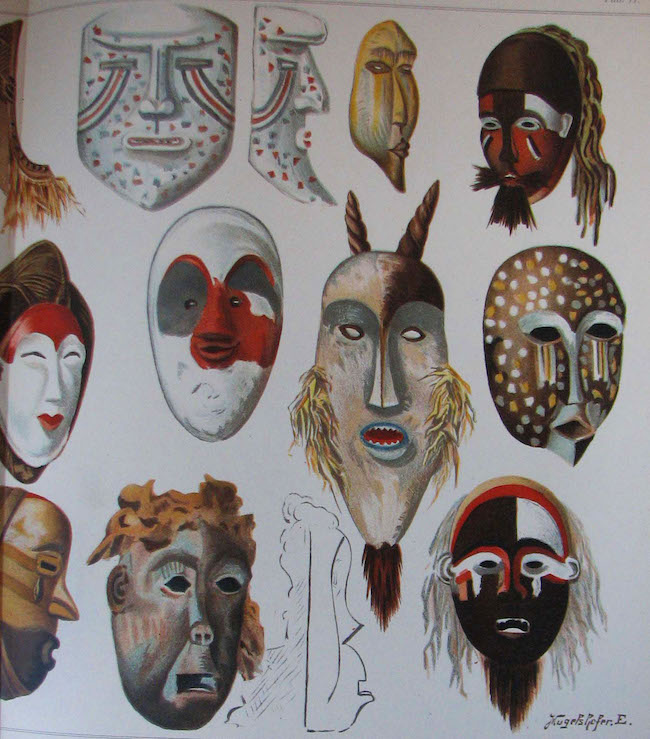

Leo Frobenius, Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas, Hall, Germany: (C) E. Karras, 1898.

Professor Blier uses her specialization in African art history to buttress her “discovery” of new, never-before-consulted sources that promise to further illuminate our understanding of the painting. These sources are Leo Frobenius’ Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas (African Masks and Secret Societies), published in Germany in 1898 and translated into French that same year. And Carl-Henrich Stratz’s Die Schönheit des weiblichen Körpers (The Beauty of Women’s Bodies), originally published in English in 1898, German in 1899, and in French in 1900.

However, on pages 16-17 of her book, Professor Blier writes: “While we have no direct evidence that Picasso saw or studied these books (e.g., the finding of actual volumes in his collection or notes indicating these specific titles), it is clear that he knew them well, as evidenced through his changing visual and intellectual engagement with them… As with Picasso’s other sources, it is important to emphasize, however, that there is very little evidence in Les Demoiselles or its related studies that suggests that Picasso was engaged in directly copying the images. They are springboards to thinking about new kinds of forms and relationships.” I am lost here.

Why are we reading about possible sources for Picasso’s masks and female types when there is “no evidence” the artist had access to these volumes? What is to be gained from this mode of inquiry? Do we learn more about this work of art? Not really. We learn about Frobenius’ and Stratz’s books, which may be relevant for other art history research, but not in the context of Picasso’s references to African and Oceanic art.

“The Bateau Lavoir,” 13 rue Ravignan, off Place Emile Godeau, Montmartre, c. 1910. (C) Wikipedia Commons

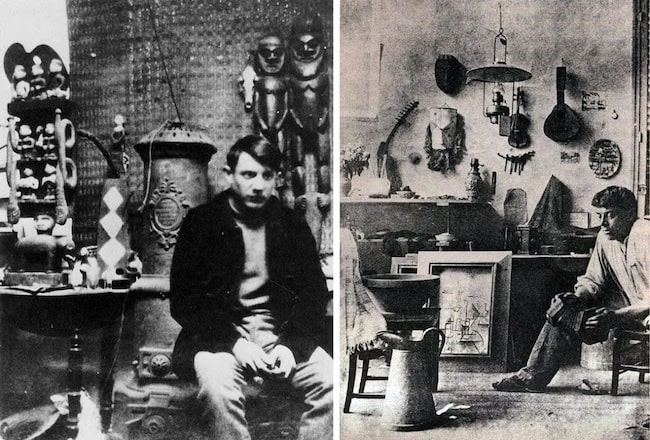

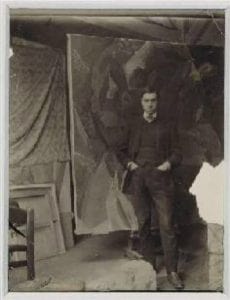

Pablo Picasso in his studio, 1908, in the “Bateau Lavoir” and Georges Braque in his studio, 1911 (C) Unknown author

Picasso’s access to his own collection, the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro , his friends’ collections, and the dealers within his purview would have been sufficient for his needs. First and foremost, Picasso enlisted the formal attributes of African and Oceanic art to achieve a sense of liberation from academic practices. We do not need to identify specific masks or illustrations of masks to understand Picasso’s innovative composition and execution, which are the extraordinary revelations of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. We need to understand the painting itself, its formal features (line, space, color, composition) that launched Picasso’s Cubist vocabulary and this revolutionary art movement.

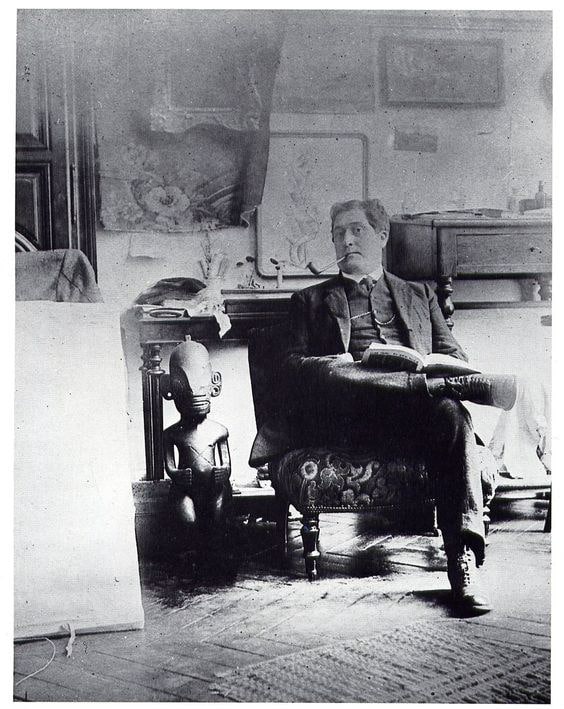

Guillaume Apollinaire in Picasso’s studio, 1910. (C) Wikimedia Commons

Yes, there are African references, colonialist appropriations, and pathetically bored grimaces staring back at us from an enormous canvas of 8 x nearly 8 feet square. Yes, Picasso was racist and sexist, a product of contemporary white European male culture. Agreed. However, Blier’s attempt to racialize each figure to set up an iconographic reading of this “global brothel” seemed overreaching at best. Also, her understanding of Picasso’s relationship to Spanish “blackness” lacked the coherence of Natasha Staller’s A Sum of Destructions: Picasso’s Cultures and the Creation of Cubism (Yale University Press, 2001), a fascinating and beautifully written book that deserves more attention.

Moreover, racializing Picasso’s color palette may complicate matters further, distorting Picasso’s primary intention. The painting was not created as a colonialist artifact or as an anti-colonialist critique (Patricia Leighten’s contribution to Demoiselles lore); it was created to revolutionize the direction of art. Fully aware of historically significant inflections, Picasso chose the female nude, rather than, say, a still life, to make his case.

In an eyewitness account called “An Anecdotal History of Cubism,” his second chapter in La Jeune Peinture française, Salmon wrote:

“Already, the artist was passionately fond of Black artists, whom he placed well above the Egyptians; his enthusiasm was not based on a vain appetite for the picturesque. Polynesian or Dahomeyan images seemed rational to him. Picasso inevitably gave us an appearance of the work that did not conform to the way we learned how to see it… For the first time in Picasso’s work, the expression of the faces is neither tragic nor passionate. They are masks that are almost liberated from any humanity… They are naked problems, white cyphers on a blackboard. The sober principle of the painting-equation was set down.”

In other words, Salmon believed that Picasso’s painting addressed the current state of art in a sober, scientific fashion. The sentimental had to shift to the analytical by subverting and disrupting the delectation of the female nude, the very site upon which traditional academic art builds its foundation. By experiencing the tactile as well as the visual attributes of African and Oceanic art, Picasso decided that here were his spiritual mentors.

Salmon continued: “In it he created atmosphere through a dynamic decomposition of luminous power; an effort that left the endeavors of Neo-Impressionism and Divisionism far behind. Geometric signs — a geometry at once infinitesimal and cinematic — appeared as the principal element for a style of painting whose development nothing could stop from then on. …it is about painting itself, about art on a surface, and that is why Picasso, in his turn, has to create these balanced figures outside the laws of academicism and an anatomical system, while situating them in a space rigorously conforming to the unforeseen freedom of their movements.” Thus, Picasso turned his back on his poetic naturalism in search of a “conceptual” visual vocabulary, bordering on, but not fully embracing, pure abstraction.

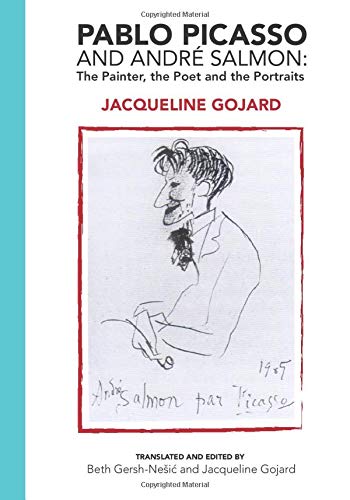

Picasso-Salmon Book Cover (C) Picasso-Salmon Book

In fact, we see the influence of Egyptian and African art on Picasso’s thought-process in sketches of André Salmon, who spent the summer of 1907 in Paris with Picasso and his girlfriend Fernande Olivier while they all lived in the dilapidated studio building located in Montmartre, affectionately nicknamed the “Bateau Lavoir” (The Washboat). An essay on this period when the Spanish artist drew caricatures of the French poet and the poet returned the favor with caricatures of the Demoiselles’ artist appears in the book Pablo Picasso and André Salmon: The Painter, the Poet and the Portraits (Za Mir Press, 2019), written by Jacqueline Gojard, Professor of Literature, University of Paris III (Sorbonne Nouvelle). Elsewhere, in the revised translation and annotations of La Jeune Peinture française (Za Mir Press, forthcoming), Professor Gojard points out Salmon’s concept of “energy” in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the “dynamic,” which we also see in numerous sketches of Salmon.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863.

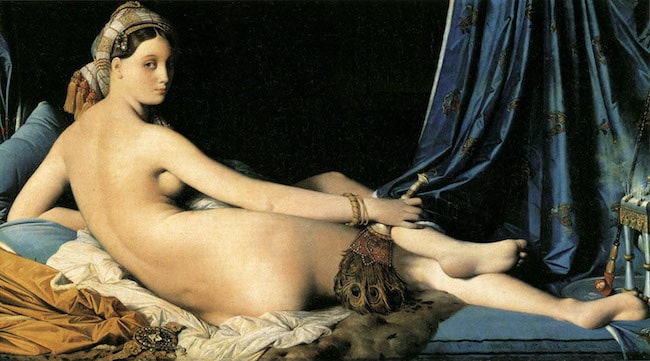

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalesque, 1814 (C) Unknown author, Public Domain

This “energy” combined with frightening female faces provoked a “shock and awe” much like Édouard Manet’s Olympia, painted in 1863 and accepted into the annual Salon in 1865. Now considered a major masterpiece, Manet’s prostitute and her black maid confront the newly arrived customer much like Picasso’s brothel denizens acknowledge our presence as we stand in front of their gathering. Perhaps Picasso decided on prostitutes and not bathers, like his friends and colleagues Henri Matisse and André Derain, who chose the latter for their entries in the 1907 Salon des Indépendants, because he had studied Manet’s Olympia at the Louvre earlier that year.

During the first week of January, the Musée du Louvre welcomed Manet’s notorious Olympia into its halls and hung it next to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ much revered La Grande Odalisque (1814), a favorite example of Romantic Orientalism. The pairing of the two met with immediate critical outrage and condemnation. Remember that in 1865, the critics attacked Olympia’s poorly rendered contours. The whole composition looked flat in comparison to the standard academic painting. Although a bit mannered in its style, Ingres’ nude continued to support classical probity, that moralistic adherence to academic rigors. No one in the art world ignored the Louvre’s magnanimous gesture, which signaled Manet’s acceptance into the pantheon of French culture.

Itching to make his own mark in art history, like Manet, Picasso too envisioned a release from academic conventions, most notably the rules his father the artist Don José Ruiz y Blasco enforced throughout his childhood and adult training. Picasso needed to take control of his career on his own terms. Les Demoiselles would not only revolutionize art, it would also emancipate this son from his art instructor papa.

The whole project produced no less than 809 sketches. Each rehearsed the 25 year old’s desire to transgress classical beauty and his well-entrenched academic training. In its stead, he produced geometrically organized human figuration, unprecedented monstrosities, locked in an unfathomable vortex of interlocking planes. In 1907, the painting seemed incoherent and worrisome. Could it be a sign of an impending nervous breakdown, à la Van Gogh? We know his friend, the “wild” and crazy Fauve André Derain, joked that Picasso might end up like Émile Zola’s character Claude Lantier, the artist in L’Oeuvre (The Masterpiece), 1886, who hangs himself at the end of the novel.

Fauves exhibition at the Salon d’Automne, reviewed in L’Illustration, November 4, 1905 (C)

The unconventionally proportioned female body may not have fazed Derain himself, as he and Henri Matisse had already exhibited anatomical deformations in the 1907 Salon des Indépendants. However, Picasso’s rough surface and his rapidly applied, multi-tonal strokes slathered on and around each figure challenged his colleagues’ threshold of acceptance. The whole ensemble militates again the requisite coherence that any professional artist, progressive or conservative, deemed significantly substantial.

This philosophical shift may have inspired the painting’s first nickname “The Philosophical Brothel” credited to the poet/art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who referenced the Marquis de Sade’s book La Philosophie dans la boudoir (1795). What could a “philosophical” brothel mean to this esoteric entourage? We know that de Sade’s ostensibly sexual romp deftly masks a political polemic in favor of libertine values and atheism. Insinuating a hidden agenda may have been Apollinaire’s take on Picasso’s motivation, but Salmon disagreed, insisting the artist demonstrates aesthetic freedom, not a political or moralistic opinion.

André Salmon in front of Three Women in Picasso’s studio, 1908 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is on the left under the cloth sheet. (C) Wikimedia Commons

And what about the painting’s physical history? What might we learn from its strange lighting and familiar composition? In 2015, the director of the Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont, Janie Cohen curated Staring Back: On Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, an inventive, tech-based exhibition that considered the painting’s history, iconography, and origins in early 20th-century Paris. We also learn about Cohen’s published scholarship on the influence of ethnographic photography, examples of which were found in Picasso’s personal collection. The exhibition also included postmodern appropriations of Les Demoiselles to consider the work in terms of our contemporary sensibilities.

Only Cohen’s show reminds the viewer that this huge masterpiece started out in a dim studio by day that was candle-lit at night. Here a flickering video projection by Coberlin Brownell in collaboration with Damian Elwes in a darkened alcove helps us imagine the original experience of viewing the canvas in Picasso’s Bateau Lavoir studio. How do we know Picasso worked by candlelight at night? Salmon described this scenario in his memoir, Souvenirs sans fin, volume I (1955). In Staring Back Picasso’s ghoulish gals loomed out at the spectator like ghosts loitering in a cavern or cave. The ferociousness of the faces, influenced by Egyptian, African, Iberian, and Maori art, still manage to catch us off-guard, whether in photographs or in person.

Beth Gersh-Nešić, Les Demoiselles d’iPhone, 2021 From the author’s Demoiselles de New York series (C) Beth Gersh-Nešić

Today, lodged in their permanent home inside the Museum of Modern Art in New York City since 1939, the masked and naked Demoiselles d’Avignon no longer reference their first home in a Parisian slum nor their swanky digs in fashion designer Jacques Doucet’s glittering Art Deco hôtel particulier at 33 rue St. James, Neuilly-sur-Seine, from 1924 to 1929. Posing against a bright white wall, they have become freeze-dried art history markers that connect Picasso’s Rose Period to his early Cubist examples, cooperating with the curators’ educational installation. Still bizarre and brazen, these damsels seem unexpectedly dated next to their neighbor Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20: Die (1967), which pays homage to Picasso’s Guernica of 1937, not his Demoiselles of 1907. Is this another problematic reading of these Mistresses of Modernism? Are we to glean that these are Les Demoiselles de Race Relations?

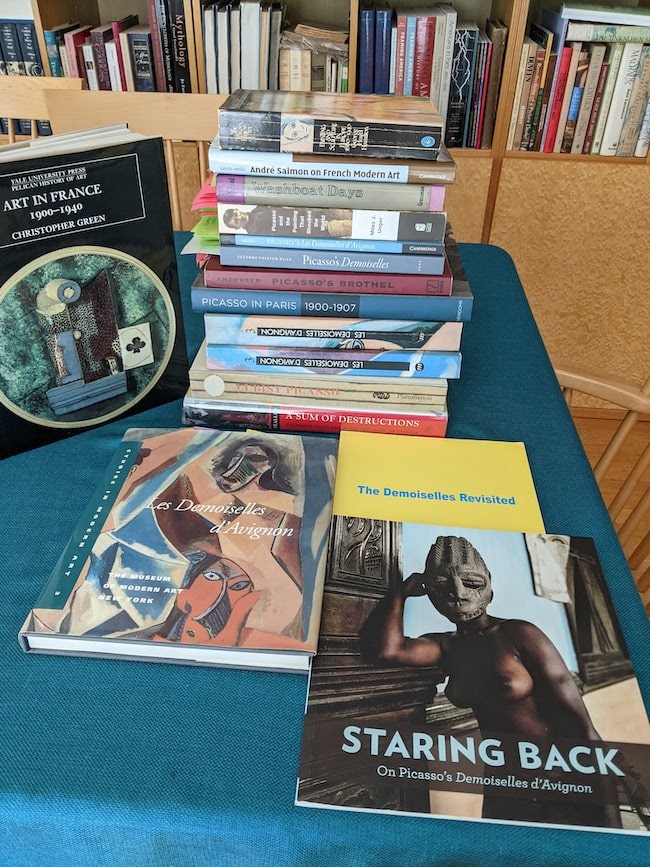

Demoiselles books in a stack (C) Beth Gersh-Nešić

Enough of these reductive attempts to crack the code of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Instead, let us celebrate what is inarguably evident in the painting itself. Clearly, what Picasso produced here changed the course of art. He succeeded, as the whole Museum of Modern Art demonstrates throughout the building. However, there is still the unanswered “why.” Why did this messy, audacious, and exceedingly unorthodox painting gain such traction, inspiring Cubism, innumerable art historians, a whole generation of artists when it arrived at MoMA, and another generation today? This question deserves an answer. I look forward to your replies.

Lead photo credit : Beth Gersh-Nešić, Masked-Up: Demoiselles de Covid-19, June 12, 2021 From the author’s Demoiselles de New York series (C) Beth Gersh-Nešić

More in Art, book, history, painting, picasso