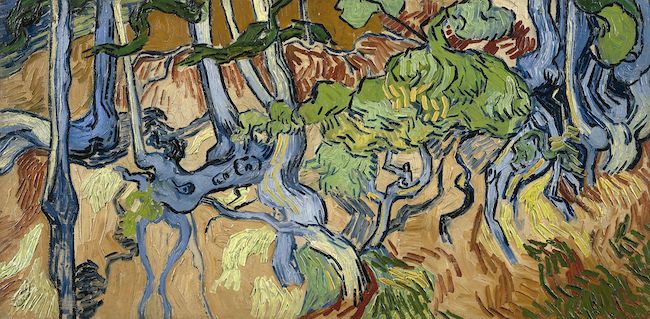

Vincent van Gogh: The “Last Painting” in Auvers-sur-Oise

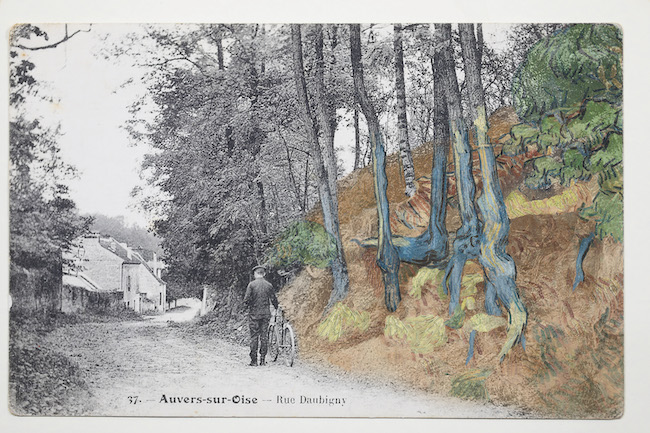

During the 130th anniversary week of Vincent van Gogh’s death, a slew of articles announced the latest revelation and revision for this tragic event. According to Wouter van der Veen, the scientific director of the Van Gogh Institute, the 37 year old Dutch artist was painting Tree Roots on July 27, 1890, at a site located about 150 meters (500 feet) from the Auberge Ravoux, before he shot himself and returned to the inn to die in his own bed on July 29, 1890. Van der Veen found a postcard from around 1900-1910 that seems to match van Gogh’s interpretative composition. His recently published ebook Attacked at the Root, is available in English and French, on his website Arthénon, at no charge, but a donation is appreciated. It is beautifully written and fascinating. Moreover, it is a project produced within the period of our global Covid-19 confinement.

Postcard, c. 1900-10, found by Wouter van der Veen, scientific director of the Institut Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise. Photo Source: Wouter van der Veen, Arthenon.com

Van Gogh spent the last 70 days of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, a small town about an hour by train outside of Paris. The fatal gunshot wound, which did not exit his body, seemed to be lodged in his abdominal cavity, close to his spinal cord. Numerous anecdotal accounts allege that the incident took place after lunch at the Auberge Ravoux, his usual routine. He had set out earlier in the day with his painting gear, rucksack and easel. Most narrators assume that van Gogh shot himself in the stomach after he had worked on a canvas. He then staggered back to the inn without his gear, where he took to his bed, suffered excruciating pain from the infection developing around the irretrievable bullet, and succumbed to this infection about 30 hours after the suicide attempt occurred.

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet, 1890, Musée d’Orsay. Photo Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia/Google Art Project

Theo van Gogh described in his letter to his wife Johanna Bonger that Vincent seemed comfortable when he arrived at his brother’s bedside on July 28th. He found his Vincent sitting up, calmly smoking a pipe. Dr. Mazery, a Parisian obstetrician on holiday in Auvers-sur-Oise, had been called immediately. Dr. Gachet, who had been treating Vincent’s mental health, arrived later that evening. The police, summoned by the inn’s proprietor’s thirteen-year-old daughter Adéline Ravoux, asked the artist: “Did you want to commit suicide?” Van Gogh responded: “I believe so.” Adding: “Do not accuse anyone. It is I who wanted to kill myself.”

Photograph from director Vincente Minelli’s Lust for Life (1956) with Kirk Douglas. Produced by John Houston.

Thanks to Irving Stone’s 1934 biographical novel Lust for Life, and the subsequent 1956 Hollywood film with Kirk Douglas in the starring role, Wheatfield with Crows has been considered his final painting at the end of July 1890. Allegedly, van Gogh had borrowed a gun from the inn’s proprietor Gustave Ravoux to get rid of the crows that had been menacing him as he worked. The painting’s agitated image has served as a visual suicide note for most scholars and van Gogh fans. Here, swirling above the golden stalks, we see a murder of crows hover like a dark cloud foreshadowing a storm. The central path, emphasized in converging verdant green lines, careens toward a definitive point, a dead end. There is no way out if one advances forward. Deciphering the symbolism of van Gogh’s dizzying road to nowhere often leads the deductive reasoner toward one conclusion: this artist decided to end it all. He would not leave this wheatfield again.

Van Gogh Museum. Photo Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia

Several interviews recorded by those living in Auvers-sur-Oise during van Gogh’s final days have produced an impressionistic image of van Gogh’s mental health. He had left St. Rémy, where he received treatment from 1889 to May 1890. His friend and his brother Theo’s friend Impressionist Camille Pissarro suggested that Vincent seek out therapy with Dr. Paul Gachet in Auvers-sur-Oise, and initiated the arrangement.

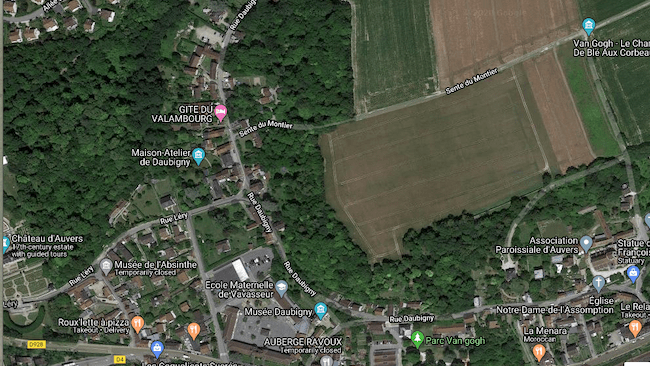

Map of Auvers-sur-Oise, retrieved from Google Maps

Vincent van Gogh’s lucid declaration “do not accuse anyone” struck van Gogh biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith as a bit ominous. Why would the artist anticipate this suspicion and immediately silence any further thoughts? In their 2011 book Van Gogh: A Life, the biographers traced the life and death of Dutch artist through to the assumption that Wheatfield with Crows was his final painting at the end of July 1890. Naifeh and Smith noted, as they walked the half-mile from the wheatfields behind the château to the inn, that the distance would severely tax a wounded person. How was it possible to survive the journey under such duress? Most accounts had claimed he shot himself, fell unconscious and then slowly trudged back to the Auberge Ravoux. Naifeh and Smith didn’t buy it and investigated further. Their findings accuse a group of teenagers, specifically René Secrétan, a Parisian who summered in Auvers-sur-Oise, as the culprits. René had pranked his brother Gaston’s “crazy, Dutch” friend on numerous occasions, and yet Vincent liked Gaston, enjoyed conversing about art with Gaston, and therefore indulgently suffered René’s remorseless taunting.

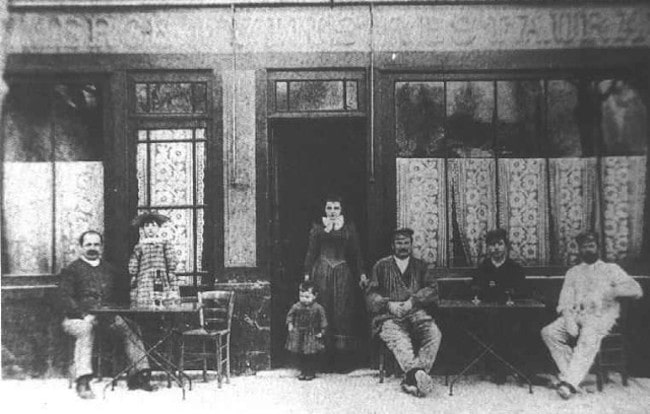

Auberge Ravoux, c. 1890, with, from left to right, Arthur Gustave Ravoux, Germaine Ravoux, Raoul Levert, and Adéline Ravoux. Photo Source: © Van Gogh Museum

In the Naifeh and Smith biography, the fatal gunshot was described as an accident involving a small-caliber gun in René’s possession. The authors’ interview on the CBS’ new magazine 60 Minutes pointed out the missing rucksack, canvas, painting gear, and “suicide” gun in these eyewitness reports. What happened to them after van Gogh’s death? They seemed to have vanished. Julian Schabel’s film At Eternity’s Gate, based on the 1998 book At Eternity’s Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh by historian Katherine Powers Erickson, Ph.D., concludes with a similar scenario. Van Gogh had not committed suicide, but instead had been accidentally murdered.

Contemporary photograph of the site for Tree Roots and Trunk, rue Daubigny. Photo © arthénon

But not all art historians agree. Van Gogh specialist Martin Baily wrote in September 2018:

“For me, the most convincing evidence for suicide is that this is what was believed by Theo and the artist’s colleagues. It is also what Vincent himself said, if we are to believe the words of his loyal friend Émile Bernard. In a letter to the critic Albert Aurier, Bernard wrote two days after the funeral, which he had attended: ‘his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity’. This is what Theo had told Bernard. Additional evidence is the fact that the artist also appears to have attempted suicide while at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, a few months earlier.”

To buttress Bailey’s assertion, the alleged “suicide gun,” a 7 mm small-caliber pistol, was found behind the château in Auvers-sur-Oise in 1960 and given to the current owners Roger and Micheline Tagliana of the Auberge Ravoux, who left it to their heirs. The gun fetched € 162,500 (about $182,000) at Rémy Le Fur and Associates’ auction in Paris on June 19, 2019.

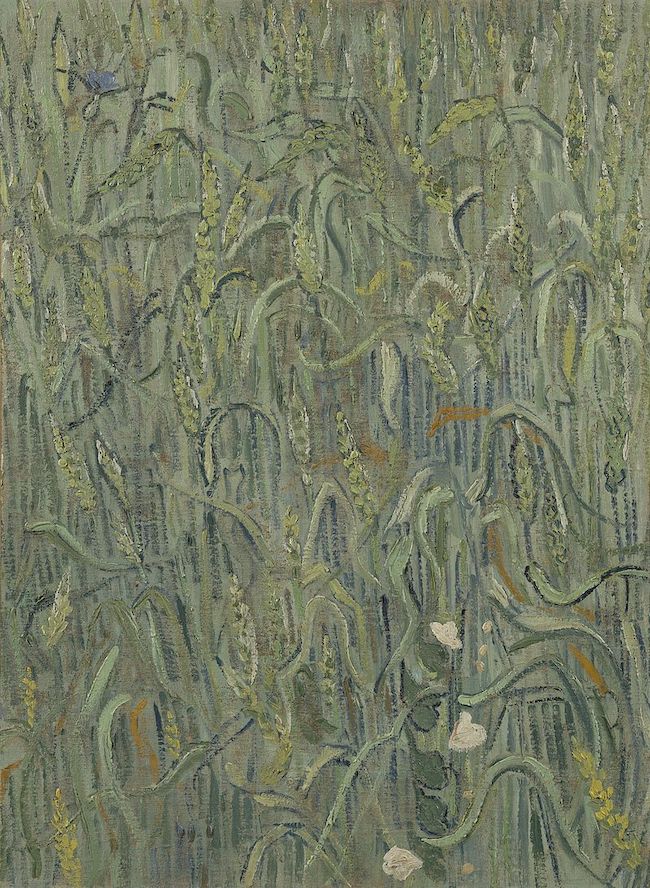

Vincent van Gogh, Ears of Wheat, June 1890, Van Gogh Museum. Photo Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia

The question to ask at this point is whether or not ascertaining Vincent van Gogh’s death as suicide really matters? In my opinion, it does not. Yes, van Gogh suffered from mental illness, but his artwork is not about the illness itself or the experience of being a person with a mental illness. Therefore, the artwork should not be pathologized in order to study an artist, who willingly sought treatment for his mental instability. According to the late art historian Charles S. Moffett, curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Van Gogh as Critic and Self-Critic (1973) and subsequently Executive Vice President of the Department of Impressionism, Modern Art and Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s, Vincent van Gogh painted when he was in complete control of his faculties. Dr. Erickson, in a similar vein, points to his deeply entrenched spirituality, based on his Christian faith, as the inspiration for his fervent Post-Impressionist Expressionism.

Vincent van Gogh, The Plain of Auvers or Wheatfields of Auvers, June-July 1890. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna. Photo Source: Public Domain/Wikipedia

The recent ballyhoo about Vincent van Gogh’s final painting before his alleged suicide may become yet another theory, susceptible to revision based on further analyses and investigations. Worrying about when, where or if van Gogh committed suicide offers us nothing but a distorted, unhealthy approach to van Gogh’s work, and further marginalizes those who suffer from psychological afflictions. My own theory about van Gogh’s originality comes from my study of Cubism and the poets who influenced Cubism. They spoke of a “Fourth Dimension,” a space-time continuum existing beyond optical and tactile apprehension. Van Gogh seems to access this awareness before Einstein and the Cubists gave it a name. In van Gogh’s paintings, it manifests itself through the thick, sturdy impasto that vibrates with a life force, as if the artist tried to materialize the pulse of nature’s vitality. In Tree Roots, we see green growth among the gnarled anchors straining against erosion. They are resisting death, while maintaining life, firmly holding on rather than letting go.

Wouter van der Veen. Photo Source: Wouter van der Veen, Arthenon.com

Lead photo credit : Vincent van Gogh, Tree Roots, July 1890, Auvers-sur-Oise Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photo Source: Public Domain, Wikipedia

More in mental health, Van Gogh

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY