Cubisme à la française at the Centre Pompidou: Cubism at Home at Last!

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Centre Pompidou curators Brigitte Leal, Christian Briend, and Adrianne Coulondre have organized a spectacular exhibition for the maddeningly complex movement Cubism. Enormous, exhausting and exhilarating, the exhibit displays over 300 objects (art and artifacts) along a prescribed pathway that spreads over 13 sections. What is your reward for slogging through such an immense undertaking? A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience an epiphany. For here in Paris—rather than in New York, London or Philadelphia (cities that have hosted exceptional surveys of Cubism in recent years)—we come face-to-face with an indisputable fact: Cubism truly belongs to Paris. It began in Paris, it thrived in Paris and it gave birth to numerous other movements from its home in Paris. In the able hands of these curators, the history of Cubism explodes with the youthful vigor of this modernist revolution.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, winter 1909-spring 1910. Oil on canvas, 92 x 65 cm, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. @Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow/Bridgeman Images. @Succession Picasso, 2018

“Yuck!,” you might say. “Cubism is so ugly, so confusing. The title claims there’s a man with a guitar, but where’s the guy? Where’s the guitar? I really hate Cubism.” Okay, I hear you. The very word “Cubism” is a turn off. It sounds like math. It sounds boring. However, this show might surprise you. Yes, you may feel mystified by Picasso and Braque’s smoky gray “Analytic” paintings from 1909-1912 (my favorites). However, once you detect the head, shoulders and hands, you’ll figure out the whole composition. Just remember to stand far away from the painting so that you see the planes project and recede from your eyes, like a pop-up card.

George Braque, Pitcher and Violin, 1909-1910. Oil on canvas, 116.8 x 73.2 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Bâle. ©Kunstmuseum Basel, photo Martin P. Bühler.

© ADAGP, Paris 2018

Also notice in Georges Braque’s Pitcher and Violin (1909-10) the nail at the top of the composition. This legible “attribute” indicates how the light falls on the objects from a specific direction, a fairly conventional consideration for a well-trained artist. Now study the overall interpretation of objects assembled within a given space (a table, a landscape, a studio, etc). As you hunt for each item announced in the title, think about the Cubists’ notion of simultaneity, the referencing of the different sides of an object on one plane. From the pas de deux of the “Gallery Cubists” Picasso and Braque, we move on to Section 6: “Salon Cubism.”

Photograph by Beth S. Gersh-Nešić. Robert Delaunay, City of Paris, 1912 (Exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants, 1912). Oil on canvas, 267 cm x 406 cm. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. On loan to Musée de la Ville de Paris. Public Domain

Behold another vision for Cubism! Bold, radiant and large, “Salon Cubism” asserts itself in terms of size and color. This parallel strain of Cubism, also known as “Epic Cubism,” viscerally celebrates modern life in a more energized visual vocabulary, expressing its enthusiastic optimism for its beloved city, Paris, the epicenter of the artists’ world.

Photo of installation by Beth S. Gersh-Nesic. From left to right:

Sonia Delaunay, Electric Prisms, 1914.

Albert Gleizes, Soccer Players, 1912-13.

Robert Delaunay, Cardiff Team, 1912-13

The most important feature in the Centre Pompidou exhibition is its generous display of the “Salon Cubists” who often appear as secondary in the predominately Picasso and Braque narrative. Make no mistake, the Centre Pompidiou show exhibits plenty of Picassos and Braques. However, the revelation for this New Yorker was the sheer quantity of huge “Salon Cubist” paintings, especially those that rarely travel to our shores. In Room 8, the installation of three large works by “Salon Cubists” Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes in one corner helps us imagine the artists’ fascination with early 20th-century innovations: technology (in this case, electricity) and various sports teams. This group demonstrates not only Cubism’s interpenetration of planes in space, but also the Cubists’ belief in the fluid intersection of everyday life and art, what Apollinaire called the poetry of circumstance.

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning, Paris, spring 1912. Oil cloth, oil paint, canvas and rope, 29 x 37 cm. Musée National Picasso. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso, Paris) / M.Rabeau. © Succession Picasso 2018

What were the differences within the Cubist movement? Picasso, Braque and Juan Gris, known in scholarly literature as the “Gallery Cubists,” exhibited exclusively in Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s small space at 28 rue Vignon. The “Gallery Cubists” received a stipend from Kahnweiler, which may account for the greater quantity of their production. Their work reached the select few who frequented their studios and/or Kahnweiler’s gallery.

Photograph by Beth S. Gersh-Nešić. Left to right: Fernand Léger, La Noces, [1911?].

Jean Metzinger, Woman on a Horse, 1911-12.

Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Fernande Léger, and many others are called the “Salon Cubists,” because they exhibited in the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indépendants (Spring Salon), which brought in the general public. “Salon Cubism” was the public face of the movement. Therefore, the works by these artists established the public’s understanding of the Cubist brand. (Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger furthered this publicity by teaching the Cubist method at their Académie de La Palette in Montmartre, beginning in 1912.)

A photo of the Salon d’Autome, October 1 – November 8, 1912.

The two Cubist camps attracted different audiences and different markets, according to David Cottington in his catalogue essay “Cubisme et Cubismes” and his book Cubism and its Histories:

“The Parisian avant-garde formation . . . was not monolithic; its social topography, the differences of market orientation between salon and gallery cubism, the relative lack of overlap between the patrons and supporters of each (the preference of the dénicheurs for buying from dealers and studios in Montmartre rather than from the salons . . .), the differences in the aesthetic preoccupations, and the responses to the nationalistic call to order, of the two groups of artists and their milieux—these factors make such a reading of the derivative qualities out of pictorial chronology alone highly questionable. . . . the salon cubists did not meet Picasso personally, and Gleizes and Le Fauconnier did not set eyes on gallery cubism, until after the Salon d’Automne of that year [1911].” (Cottington, Cubism and its Histories, Manchester University, 2004, p. 61).

With Cottington’s perspective in mind, we notice that the Centre Pompidou curators’ linear route from Picasso and Braque to Le Fauconnier, Metzinger, Gleizes, the Delaunays, etc., seems to infer that the “Salon Cubists” were derivative followers, orbiting around Picasso and Braque’s authentic core endeavor. Cottington tells us that this assessment of the Salon Cubists would be wrong. Both groups flourished separately, fueled by their different support systems in the art world.

Robert Delaunay, City of Paris, 1912. (Exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants, 1912). Oil on canvas, 267 x 406 cm. Centre Pompidou, Musée National de l’art moderne, Paris. On loan to Musée de la Ville de Paris. (Public Domain)

Now that we know how significant “Salon Cubism” had been in its time, we can immediately appreciate Robert Delaunay’s gigantic City of Paris (1912), which fills an entire wall and dominates one of the largest galleries in the show. Here, the sheer magnitude of Delaunay’s heroic vision communicates the exuberance of the Salon Cubists’ spirit. For their work imagined a successful marriage of classicism (symbolized by the Three Graces) and French modernism (symbolized by the Eiffel Tower).

Pablo Picasso, Houses on the Hill, Horta de Ebro, summer 1909. Oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm. Nationalgalerie, Museum Berggruen (SMB), Berlin. © BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / J.Ziehe. © Succession Picasso 2018

“But what is Cubism?,” you might ask. Cubism is a conceptual notion of a real object in space. In that respect, it is a kind of realism, for it tries to capture the true physical three-dimensionality of an object on a two-dimensional surface. All the Cubist artists knew how to draw in terms of Renaissance perspective. The Cubists rebelled against these academic exercises in order to depict the experience of knowing an object through one’s own memories of the object in space, an accumulation of perceptions. Therefore, they rejected Renaissance perspective in favor of another approach to intellectual perception. They decided to depict the different views of an object from all sides at once on a two-dimension surface or in a sculpture.

Juan Gris, Breakfast, October 1915. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 92 x 73 cm. Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’art moderne, Paris. © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Philippe Migeat/Dist. RMN-GP

For example, consider an ordinary wine bottle. The mouth and bottom of a bottle are round. We don’t have to see the top and bottom to know they are round. In our memory we see the bottle’s top and bottom are round, because the bottle, in our real life experience, is a cylinder; it is round. This circular form is the bottle’s truth, its reality. The representation of a bottle’s bottom as a circle attached to the outline of its profile view references its concrete reality in space. In this respect, Cubism can be considered a conceptual realism, rather than a perceptional realism.

Pablo Picasso, L’Aficionado, summer 1912. 134,8 x 81,5 cm, Kunstmuseum Basel, Bâle. © Kunstmuseum Basel, photo Martin P. Bühler. © Succession Picasso 2018

In Picasso’s L’Aficionado (1912), we see the artist’s depiction of legible “attributes” (i.e., the pipe, the eyes, and the mustache) to establish the identity of the sitter. Then we see multiple perspectives of the head representing simultaneously before our eyes. These simultaneous views reflect our conceptual understanding of an object, the way we see it in our minds. As André Salmon, the author of “An Anecdotal History of Cubism,” published in La Jeune Peinture française (1912), often wrote in his other recitations on Cubism: “conception triumphs over perception” in this approach to art.

Paul Cézanne, Portrait d’Ambroise Vollard, 1899. Oil on canvas, 101 x 81 cm. Petit Palais, Musée des beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris. © Petit Palais/Roger-Viollet

Cubism began as an idea and then it became a style. Based on Paul Cézanne’s three main ingredients—geometricity, simultaneity (multiple views) and passage (pronounced in the French way), Cubism tried to describe, in visual terms, the concept of the Fourth Dimension (time). As we walk through the first gallery, we see works by Cézanne and Paul Gauguin who laid the foundations for Cubism. Notice the folds and lapels in Cézanne’s portrait of his art dealer Ambroise Vollard. The overlapping and interpenetration of these planes blend into each other, blurring the boundaries between the planes and the contours of objects in this pictorial space. This blurring is called “passage.” Passage helps us think about the apperception of an object in time as well as in space.

Jean Metzinger, Woman on a Horse, 1911- 1912. Oil on canvas, 162 x 130,5 cm. SMK, Statens Museum for Kunst, National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. © SMK Photo/ ADAGP, Paris 2018

The literal space of the canvas becomes its own reality with its own rules. Besides Cézanne’s geometricity, simultaneity and passage, the Cubist image often operates in terms of a grid, evident in Jean Metzinger’s Woman on a Horse, 1911-12. Here the “push-pull” of Cubism, as the German artist Hans Hofmann would explain to his students in the 1930s-40s, gives rise to a figure and ground tension, the basis for most of modernism’s abstract expressions (Pepe Karmel’s exhibition essay “Cubisme et Abstraction” informs us about this aspect of Cubism’s legacy).

Anonymous, Krou (Grebo) Mask, Ivory Coast, n.d. Wood, 25,5 x 16,5 x 18,3 cm. Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon. © Lyon MBA – Photo Alain Basset

African and Oceanic art also played a role in the development of a Cubist vocabulary. André Derain, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire collected artworks from sub-Sahara Africa and the South Seas. The artists’ forays into making sculpture (on view as well) demonstrate their attempts to emulate the strong geometric elements they admired in these non-Western traditions. To Picasso, African and Oceanic art felt magical.

For this exhibition, Picasso’s 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was not lent by its owner the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Instead, a few contemporary paintings and sketches for the Demoiselles summarize the influence of this period on Picasso’s Cubism.

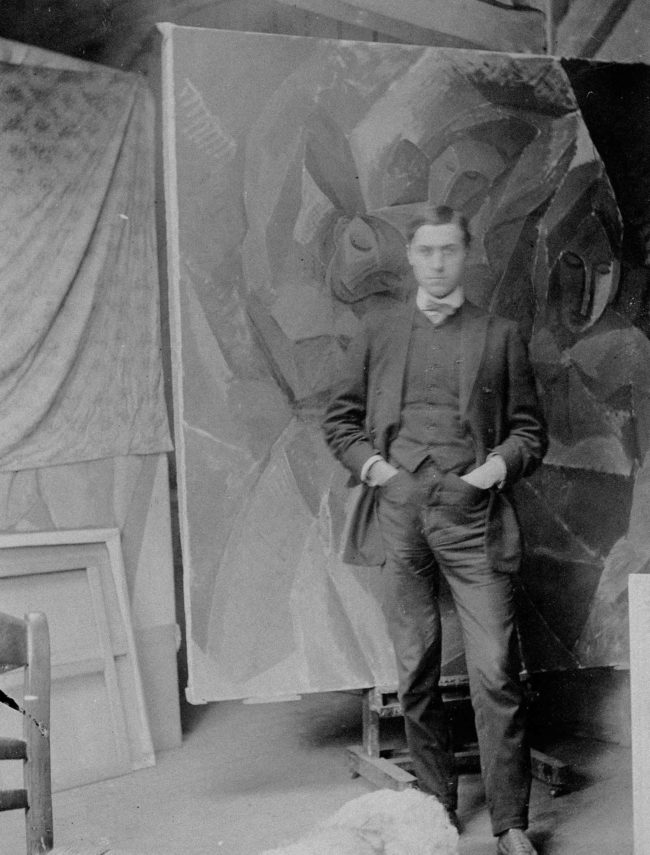

André Salmon in front of Picasso’s Three Woman, 1908. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is on the left, covered with a patterned cloth. Photo: Public Domain.

We should remember that Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was not exhibited in public until July 1916, so its influence must have been quite narrow. As far as we know, only Picasso’s close friends and a few dealers were invited to see the work. We can see in this 1908 photo that the artist hid the painting under a cloth in his studio.

Georges Monca, The Cubist Painter Rigadin, 1912, Actors: Georges Prince and Gabrielle Lange, Fondation Jérôme Seydoux Pathé

Cubism inspired numerous satirical responses in humorist drawings and in film. The Centre Pompidou exhibition included one short silent film, Rigadin the Cubist Artist, the story of a conventional artist who decides to dress in cubified clothing and paint cubes on canvases in order to impress his clients. Lampooning modern art movements become common practice for those writers and satirists who catered to the general public’s taste and preferences. Most felt an antipathy toward avant-garde trends.

Georges Monca, The Cubist Painter Rigadin 1912; Fondation Jérôme Seydoux Pathé

For many audiences, Cubism seemed to be a scam or a practical joke that deliberately deceived gullible art-lovers and collectors. In the exhibition catalogue, we do find references to the negative art criticism in “‘C’est la géométrie dans les spasmes!’ Le cubisme dans la presse (1908-1919),” written by Ariane Coulondre. However, Cubism received more than nasty reviews, it also provoked xenophobic sentiments since many of its artists were foreign: Picasso came from Spain, Marc Chagall from Russia, Jacques Lipshitz from Lithuania, Alexandre Archipenko from the Russian Empire (today’s Ukraine), and so forth. Racist and anti-Semitic slurs tried to characterize Cubism as a conspiracy determined to ruin French culture. The challenge of curating a comprehensive exhibition of Cubism, therefore, requires some acknowledgement of this unpleasant reception. With this in mind, one hopes for an exhibition on Cubism that practices Cubism itself. That is, a willingness to show the whole story from all sides at once, even the ugly sides one would like to forget. The Centre Pompidou curators have tried to fulfill this task and, for the most part, they have succeeded.

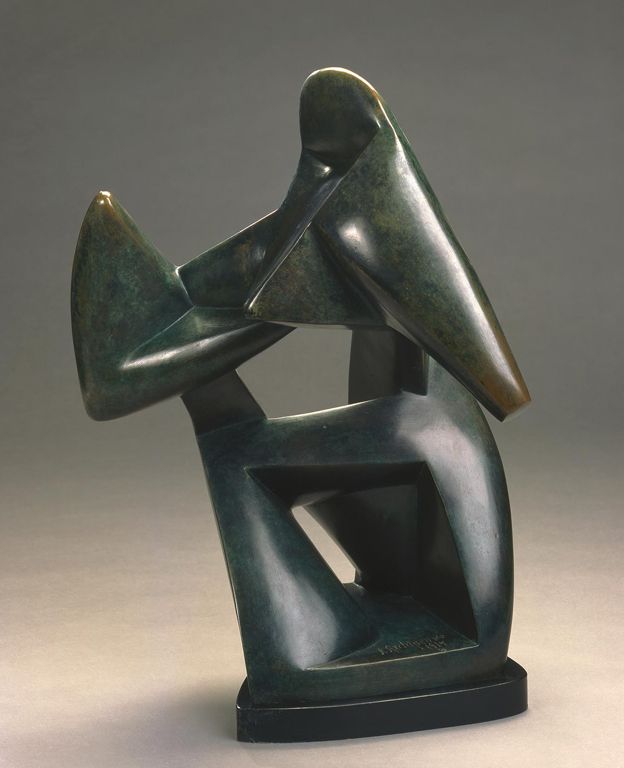

Alexandre Archipenko, The Boxers, 1914.

Plaster cover with black, 60 x 43 x 37,5 cm. Saarland Museum – Moderne Galerie, Stiftung. Saarländischer Kulturbesitz, Sarrebruck. ©Saarlandmuseum – Moderne Galerie, Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz, Sarrebruck. © Estate of Alexander Archipenko / ADAGP, Paris 2018

If you have the good fortune to be in Paris from now through February 24, please make an effort to walk through the history of Cubism in the city that inspired its ardor. The next venue will be the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland, from March 30 through August 4, 2019. (NB: the beautifully illustrated exhibition catalogue for Le Cubisme is only French at Centre Pompidou. It will be available in German and English for the next venue.)

Centre Pompidou, Place Georges-Pompidou, 4th. Open every day from 11 am to 9 pm, except for Tuesdays, when the museum is closed. Full price ticket is 14 euros.

More in centre pompidou, Cubism, picasso