62 Years of Continuous Absurdity: Ionesco at the Latin Quarter’s Theatre de la Huchette

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

One day in the late 1990s I was wandering down what at the time was one of my favorite Paris streets – the narrow, funky, and sometimes annoyingly touristic Rue de La Huchette in the Latin Quarter, a street that parallels and runs just one block south of the quai of the Seine, and stretches between rue Saint Jacques on the east and Boulevard Saint Michel on the west (where I purchase French paperbacks at Gibert Jeune’s main location).

Just past some of the gift shops and ethnic restaurants, a historic jazz club, and a man selling small Eiffel tower replicas, I spied a little theater with an old fashioned marquee. Each letter appeared to have been placed on the back lit surface by hand. I envisioned a little man on a ladder. There was also an ancient ticket window– a small square window that slid open to reveal the face of an elderly ticket taker sitting at a cashbox. The entire entrance was covered with almost life-size pictures of folks in early 20th century costume: a policeman in a tall English Bobby type of hat, a female servant with a long white apron, a woman in a long dress and a straw hat.

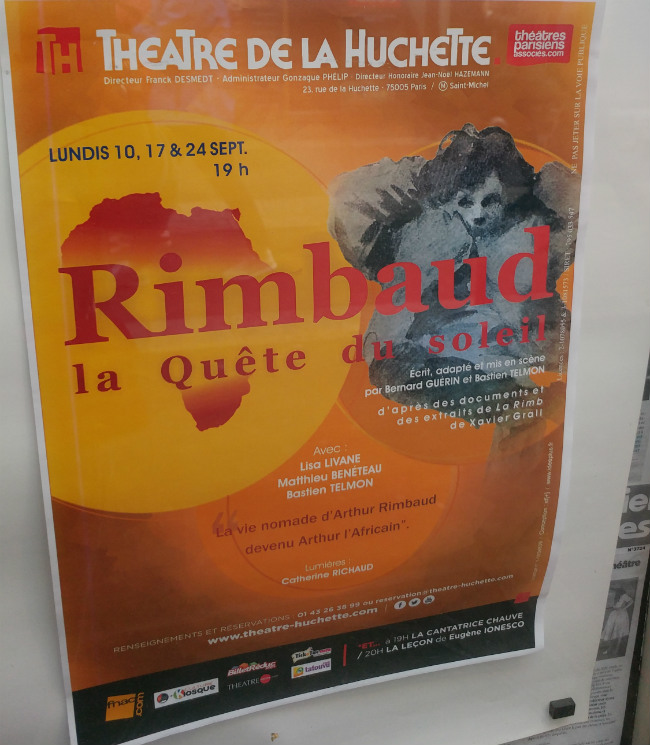

Intrigued, I stopped to check it out, and found that this little theater– Theatre de la Huchette at 23 rue de la Huchette– featured regular daily showings of Eugene Ionescos’s first two absurdist plays – La Leçon (The Lesson) and La Cantatrice Chauve (The Bald Soprano) and had been doing so continually since 1957! It still does – five days a week!

Theatre de la Huchette. Photo: Michele Kurlander

I bought tickets and attended later that day, sitting in one of the 85 red seats in this very intimate and old-fashioned theater. I have returned a number of times over the years since then, the last being September 2018 when I sat in the first row and felt eerily as if I were in the living room with the Smiths.

The experience is unlike any other theatrical experience I can think of – interesting, exciting, annoying, frightening, and humorous, all rolled into a very short period of time and involving characters whose dialogue sounds normal but is definitely not.

The plays are curious and sometimes comical and often confusing; still they draw you into them. It is a strange, very strange process. Interesting, annoying, confusing, but somehow addictive.

Each play lasts only an hour. Unlike Becket’s En Attendant Godot – which you really have to commit to since it is a full length play – these plays allow you to experience the Theater of the Absurd in small and digestible bites.

Theatre de la Huchette. Photo: Michele Kurlander

Though you can elect to purchase a ticket to only one, it is sensible to see both together since they are each only an hour long and are shown back to back, and the tickets are deeply discounted if you are seeing both plays together.

The plays are performed as written, entirely in French — except for Wednesdays when the theater recently started adding English subtitles to Le Cantatrice Chauve. (If you purchase an English version of either of the plays you can read it quickly and then have little problem understanding what they are saying on stage in the French version.)

You should know, however, that whether you are fluent in French or read the plays first in English, or bring a copy of the French version to refer to during the performance, and though you may hear the words and see the action, you are likely to not really understand what is happening on stage. That is the nature of the Theater of the Absurd. Hopefully some of the information in this article, which I have found on the theater’s website and elsewhere on the internet, will help the reader’s understanding.

The connection of the characters and their motivations and their dialogue to the reality of expectations in this world is, in these plays, somewhat tenuous. That is the nature of Absurdity.

Theatre de la Huchette. Photo: Michele Kurlander

La Leçon has three characters – a professor, his new student (an 18 year old girl who arrives with her notebook at the beginning of the play), and his irascible housekeeper.

It starts out with the student and teacher exchanging pleasantries and the teacher asking questions about the girl’s educational background and expectations, but rapidly descends into craziness.

I now understand the play to be an allegory of the devastating effects of total dictatorial power which turns comic absurdity into a nightmare. But until doing some reading to obtain that information, I had nothing but questions:

Why does the diminutive professor bait his new student in harsher and harsher ways, posing unanswerable questions, while she gets a toothache that hurts more and more as the play progresses, until her mood and conversation descend from happiness and excitement to total debilitation – while he moves from soft-spoken and polite to authoritarian and angry until at the end he takes out a knife and kills her – all within one act and one hour’s time? Is this a metaphor for what has just transpired in the real world? When his angry servant lady puts the knife back into its cabinet and helps him remove the body, in order to make way for the arrival of the next “new” student, you discover that every new student has died in the same manner, and they have now buried 40 bodies.

In the Bald Soprano no one is bald and no one sings. It is about a long married couple with nothing to say to each other and another couple who no longer recognize each other. When first written in 1948 it was shown in a private venue, as a comedy, but no one understood it that way. Then, the troupe elected to perform it with solemnity – and that seemed to work better.

It takes place entirely in the home of an English couple named Smith who welcome a man and a woman as guests. There is also a servant in the house and a fireman who comes to the door. In one segment, the two visitors to the Smith home who appear to be strangers converse while waiting for their hosts, and discover that they have arrived on the same train and, through further conversation they find, coincidentally, one step at a time, that they come from the same town, live on the same street, live in the same house, sleep in the same bed, and have the same child. Finally, as some of the audience – like me – giggle almost uncontrollably – they come to the conclusion that they must be married to each other.

Theatre de la Huchette. Photo: Michele Kurlander

I will uncover no more plot twists. Suffice it to say that the Bald Soprano is mostly humorous but strange and The Lesson mostly disturbing, though also strange, but both are famous examples of the Theater of the Absurd that grew in Europe after the cataclysms of World War II and Naziism. This absurdity is represented by the works of such playwrights as Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet, and Samuel Becket.

After World War II, the world was searching for meaning and theater was ready to explode because of the years of censorship and curfews that had rendered theater a dangerous pastime. Suddenly, small theatrical venues grew up all around Paris, and playwrights began writing works either expressing parody or feelings of alienation, the futility of communication, and meaninglessness of existence (Absurdism). In Absurdist theatrical works, because life has no meaning or purpose, all communication breaks down and there is irrational/illogical speech and, ultimately, silence.

According to my reading (and I don’t pretend to be any kind of an expert on this topic), absurdism began in small theaters in the Paris Latin Quarter and spread thereafter. Eugene Ionesco, though born in Romania, spent most of his youth in France and then returned to Romania where he studied French literature and qualified as a French teacher, then married and returned to France in 1938 for his doctorate but went back to Romania during the war, returning to France in 1942. It is said that the Bald Soprano was written in 1948 (first performed in 1950) because Ionesco’s not totally successful efforts to learn English resulted in his thinking of the sentences in his language course as sounding nonsensical after excessive repetition– since they repeated obvious truths such as the ceiling is up and the floor down, and, later in his English course, introduced the Smith couple who told each other how many children they had and where they lived, which to him also sounded nonsensical.

According to one biography I read, the obvious truths in the grammar primer started to become clichés and truisms, and disintegrated in the playwright’s mind into caricature, parody, and disjointed fragments of words – which became La Cantatrice Chauve – his first play.

At first Ionesco showed the play at other small theaters in the Latin Quarter, to mixed reviews. Then, he invented La Leçon and obtained the interest of Louis Malle who moved the two plays together into Theatre de la Huchette – where they finally found an audience, including the likes of Sophia Loren, Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier.

As for the birth of the Theatre – its website tells the story of young Russian exile Georges Vitaly who wandered through the Latin Quarter one night in 1947, having just won a theatrical competition, looking for a theatrical venue and he saw a pair of legs pushing a wheelbarrow up and down a small incline behind a partly raised metal shutter – which turned out to belong to his old drama classmate Marcel Pinard, whose girlfriend owned the building and had agreed to let him use it as a theater. The two got together and Pinard leased the theater to Vitaly for one franc upon the understanding that the latter would fix it up.

Between 1948 and 1952 the small theater produced many famous plays and gave jobs to what the website tells me were some of France’s “future great actors.” When Vitaly left for a larger theater, Pinard took over and continued to put on contemporary works (including those of Ionesco), and used actors such as Jean Louis Trintignant.

In 1957, filmmaker Louis Malle used the theater to put on Ionesco’s two plays for a one-month run which never ended because people kept coming, the theater kept making money, Pinard earned enough to buy some land, and the troupe also began performing all over the world and finally formed an actor’s cooperative, “Les Comediens Associes” – until 1975 when Pinard suffered a heart attack.

The troupe fought for five years after Pinard’s death to keep the theater from going under and being turned into a tourist restaurant. Finally, in 1980 the actors formed an LLC (“Theatre de la Huchette”) and started putting on a third non Ionesco play each week. And because of the full house of playgoers who come every week to see the Ionesco combo, and others to see the unrelated play, the theater is in the black and alive and well in 2019.

It is an exciting, quaint and interesting venue that feels like the Paris of old and should not be missed.

Theatre de la Huchette, 23 rue de la Huchette Paris, 5th. Metro: Saint-Michel. Tel: +33 (0)1-43-26-38-99. To make a reservation, click here.

Lead photo credit : Theatre de la Huchette. Photo: Michele Kurlander