La Samaritaine: The Story Behind the Legend

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

La Samaritaine, the ensemble of department store buildings which looms over the Seine’s Right Bank, was once considered one of the architectural delights of Paris, yet it recently stood vacant for over 16 years. A troublesome white elephant, expensive to maintain, yet impossible to dispose of, La Samaritaine is a historically protected building, regarded as an architectural monument for its use of Art Nouveau and Art Deco designs. La Samaritaine is once again in the news with its infamous redesign. But the story of La Samaritaine begins with Ernest Cognacq.

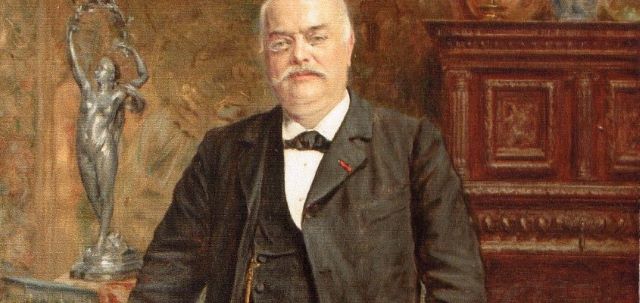

Ernest Cognacq. © The Musée Ernest Cognac in Île de Ré

The ruinous death of Ernest Cognacq’s father forced the 12-year-old Ernest to leave school and earn a living peddling novelties between La Rochelle and Bordeaux. Three years later, he sought his fortune in the great department stores of Paris. The adolescent failed at his first roles at the Au Louvre shop and Aux Quatre Fils Aymon, and retreated back to his Île de Ré home. He returned to Paris in 1856 at the age of 17 where he was a successful employee at La Nouvelle Héloïse.

There Cognac met Marie-Louise Jaÿ, a sales girl in the lingerie department, who would one day become his wife. Marie-Louise would move on to Le Bon Marché where she earned the distinction of being the first female salesperson in its clothing department. Cognacq attempted to set up on his own shop on Rue Turbigo in 1867: Au Petit Bénéfice. He swiftly went bankrupt and could be seen hawking his wares under the second arch the Pont-Neuf, near the former site of the city’s first mechanized pump, the Pompe de la Samaritaine. Under swags of red Turkish cloth, Cognacq sold linens on old, upturned crates.

Marie-Louise Jay by Jeanne-Madeleine Favier (1863-1904) – Musée Cognac-Jay Paris La Samaritaine. © Wikipedia commons

By the age of 30, Cognacq had enough saved to rent a small shopfront from a local café owner. On the corner of the Rue du Pont-Neuf and the Rue de la Monnaie, Cognacq once again named his venture Au Petit Bénéfice. This time, his business was successful. He took on two employees in 1871; one of which was Marie-Louise Jaÿ, whom he married the following year. Marie-Louise, who had developed her business acumen as a buyer for Bon Marché, helped Ernest develop his business. An active partner, Marie-Louise’s inventiveness complemented Ernest’s innovative approach to business. With Marie-Louise’s 20,000-franc dowry, and the 5,000 francs Ernest managed to save, the business prospered.

The shop renamed La Samaritaine became instantly popular with Parisians. The Industrial Revolution had spiked mass production and mass consumption. The raison d’être of Ernest Cognacq’s enterprise was to sell a large quantity of merchandise to a large quantity of buyers, at a lower price than ever before. Customers flocked in. Some of the Cognacq-Jaÿ’s innovations included haggle-proof prices which were clearly marked, and giving the customers the opportunity try on clothes before buying them. Daily promotions attracted the crowds in hope of the “deal of the day.”

La Samaritaine outgrew the small shop. The couple managed to monopolize the surrounding shops and built their ideal department store. Sales tripled between 1872 and 1874. By 1882, they took in 6 million francs. Sales rose to 40 million francs by 1895 and in 1925, sales broke the billion mark.

La Samaritaine’s success also relied on its perfect location. Ideally situated between the Louvre and Notre-Dame, customers were lured to La Samaritaine from the nearby Les Halles market and La Belle Jardinière, their closest competitor.

Two men of the arts understood the draw of the department store. Emile Zola for one understood the appeal of such places and described them in his novel Au Bonheur de Dames – The Ladies’ Paradise, first published in 1883. Not relying on imagination alone, Zola spent the best part of a month in the department stores of Paris and filled notebooks with his observations. He collaborated with the Belgian ex-patriot architect Frantz Jourdain before writing his novel. Jourdain, a pioneer in iron-frame architecture and a proponent of Art Nouveau, drew an imaginary design for Zola’s Au Bonheur des Dames. Zola’s fictional creation in turn influenced the design of actual shops.

Ernest Cognacq by Jeanne Madeleine Favier. Public domain

That same year, Ernest Cognacq came face to face with the architect that Emile Zola had used for his inspiration and Cognacq and Jourdain began a life-long collaboration. Jourdain, an architecture graduate of the Académie des Beaux Arts, adapted the pre-existing Samaritaine buildings into one and oversaw the redesign of the interior.

The Cognacq-Jaÿs called on Jourdain once again in 1905 to design the second La Samaritaine building. Jourdain began his ambitious plan. When the construction was complete, the shop closely resembled Zola’s descriptions in Au Bonheur des Dames; Jourdain’s imaginary shop became concrete. Ernest Cognacq was mostly likely the model for Zola’s energetic entrepreneur Octave Mouret.

Jourdain’s avant-garde tendencies resulted in an extraordinary building for Cognacq. Boldly embodying the Art Nouveau style, Jourdain’s architectural synthesis brought together decorative metalwork, painting, mosaic and ceramics. In this way, art was brought into the street to interact with the public. The suggestion of an oriental bazaar caught the attention of passersby. Alluring windows displayed a variety of merchandise. Yet La Samaritaine was a retailer for the average Parisian. It was a place to go for affordable goods and perhaps be entertained by in-store performances and people watching. In its way, it was an opera house for the middle class.

La Samaritaine in the 20th century

The metal frame of the building inaugurated in 1910 was visible. A purely decorative jungle of metal scrollwork embellished the rigorous lines of the exposed ironwork. The façade was adorned in a multitude of traditional Art Nouveau motifs rendered in enamel tiles and shimmering mosaic details. Spandrels were inlaid with floral ceramic tiles. Tiles also spelled out the word ‘Samaritaine.’ To add to the fantasy element, Jourdain added twin cupolas of stained glass and metalwork to the edge of the southern façade. And this was just the outside.

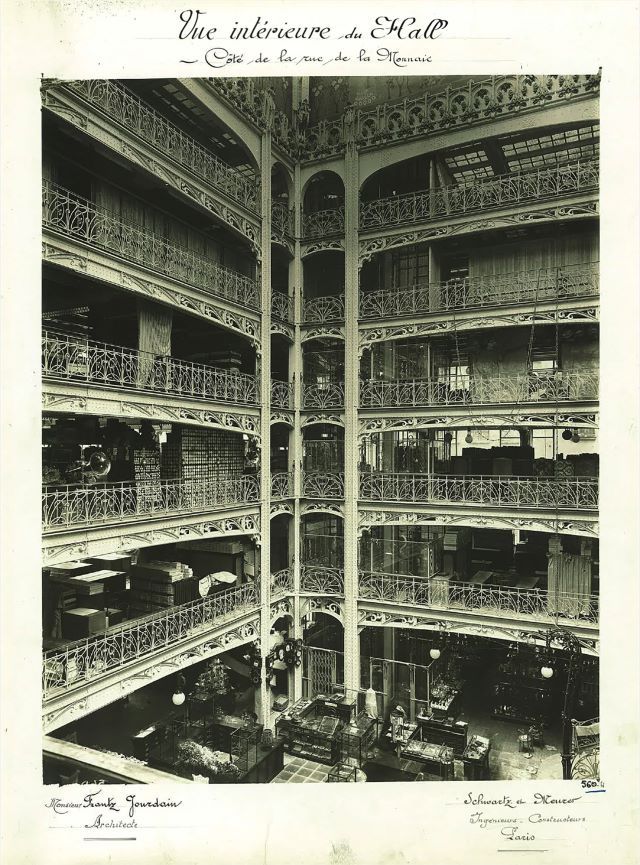

Inside, the building’s iron skeleton allowed for maximum floor space, pushing the retail floor to the outer walls. The hollow supports hid all piping and utilities. Rising to the vast glass roof, Jourdain’s atrium was a decorative masterpiece, featuring a grand central staircase, with ironwork balustrades by Edouard Schenck and ceramic details by Alexandre Bigot. An immense peacock frieze by Jourdain’s son Francis outlined the perimeter of the space.

Color was of paramount importance. Andrew Ayers in his 2003 book The Architecture of Paris reveals that the structural ironwork was painted bright blue both on the inside and exterior, while the inlaid botanical touches introduced brilliant splashes of yellow and orange. La Samaritaine became one of the architectural delights of Paris.

Alas, what was once avant-garde soon became trite. Negative reaction against Jourdain’s florid extravaganza of color became so strong that when Cognacq wanted to build on the land between Magasins 1 and 2, Jourdain’s name dare not be mentioned aloud lest planning permission be denied. Henri Sauvage, an architectural colleague, assisted Jourdain as a partner in the design of the new buildings.

Samaritaine Paris Pont-Neuf. Photo credit: We Are Contents

The associates extended the third and fourth Samaritaine stores out towards the Seine in 1930 and 1932 respectively. Henri Sauvage shaped the extension in the Art Deco style. Urban planning regulations obliged the architects to cap off Jourdain’s original metal frame beneath a stone facade. Keeping the design low key, Sauvage added stone cladding to harmonize with the nearby Louvre. Half of the grand staircase was replaced with clumsy-looking escalators.

The shop’s popularity fell in the late 1970s and 1980s. Shopping at La Samaritaine had become like playing a game of three-dimensional snakes and ladders – one step forward, two steps back. Over time each floor had developed several levels joined by sloping linoleum ramps. La Samaritaine was no longer the right store for central Paris. When the department store shut almost overnight, they inexplicably still had lawn mowers in their inventory.

In the 1980s, a restoration campaign was launched to restore La Samaritaine’s stunning Art Nouveau and Art Deco decors. The iconic building was listed in 1990 as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture and deemed a World Heritage Property by UNESCO in 1991 (as part of the Seine riverbank). La Samaritaine was bought by the world’s biggest luxury goods conglomerate, Louis-Vuitton-Moet-Hennessy (LVMH) in 2001.

La Samaritaine Facade © We Are Contents

LVMH spent the following four years upgrading the building to modern safety standards. Its original glass brick flooring didn’t pass the building code for fire safety. Judged unsafe, after a decision made by the Préfecture of Paris, La Samaritaine was shuttered on June 15, 2005. 1,506 employees lost their jobs.

After 16 years of dereliction and legal wrangles, the 150-year-old store reopened to the public on 23 June 2021. Registered as a historic monument, restoring the existing Art Nouveau and Art Deco building closest to the Seine was a very important part of the renovation. Frantz Jourdain’s multi-colored enameled tiles, hidden beneath a stone-colored wash, were uncovered. La Samaritaine’s glass roof was rebuilt following the original 1905 structural plans and its monumental staircase was restored to its former glory. Also uncovered was the fresco that bordered the top of the atrium. The gold and yellow peacocks had been hidden under layers of white paint since the 1990s. Now La Samaritaine’s glorious Art Nouveau origins are once again revealed and the atrium pays tribute to Frantz Jourdain.

La pompe de La Samaritaine et le pont Neuf, depuis le quai de la Mégisserie en 1777 (painting by Nicolas Raguenet, Musée Carnavalet). © Public domain

The other elevations of this collection of buildings have been clad with a new glass façade that reflects the nearby architecture. Some say “this set of etched glass waves” fits in with the landscape; opponents say the new structure looks like a shower curtain.

La Samaritaine’s retail offerings, restaurants and boutique hotel are targeted at affluent consumers but also contained within are 96 social housing units, offices, and a children’s nursery.

While accruing his millions, Cognacq became a philanthropist and art collector. In 1916, the couple created the Cognacq-Jaÿ Foundation developing a series of charitable works in favor of the most disadvantaged. The couple were particularly interested in the fate of orphans, the education of needy children, and the difficulties encountered by the aged. Still in operation, the Foundation has responded to recurring social needs of the vulnerable.

Ernest Cognacq and Marie-Louise Jaÿ brought together an important collection of 18th-century artwork. Marie-Louise preferred Ernest to spend his money on the female subjects in Fragonard and Boucher paintings instead of on mistresses. The collection became the Musée Cognacq-Jaÿ which was donated to the city of Paris and installed in 1929 in a building at 25 boulevard des Capucines adjoining Samaritaine de Luxe. The museum has since been relocated to 8 rue Elzévir in the Marais.

Lead photo credit : La Samaritaine © Pierre Camateros SA 3.0 wiki commons

More in history in Paris, history of shopping, Paris shopping, restaurants for people-watching in Paris, shopping in Paris

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY