Notre-Dame de Paris: Diverging Views in the 19th Century

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Much of the world collectively gasped on the evening of April 15th, 2019, when fire ravaged the iconic cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. As flames ruined the cathedral’s vaulted ceiling and licked toward the night sky, the 13th-century landmark looked every inch an illustration from a tragic gothic tale. Shocked observers wondered if Notre Dame would survive the night. Could it be saved? Could it be rebuilt? How would it be rebuilt?

Millions, if not billions, have been raised to rebuild Notre Dame and reconstruction has begun, although in a stop-start fashion as Covid-19 hinders most of 2020.

French President Emmanuel Macron has recently ended speculation over the future of Notre-Dame de Paris, stating that ‘Our Lady’s’ spire will be restored to its original design. A replica of Viollet-le-Duc’s 93m spire, added to the Cathedral in 1859, will be built as part of the reconstruction. The decision to replicate the spire aligns with a bill passed by the French Senate that stated that the cathedral’s rebuilding must be faithful to its “last known visual state.”

The Notre-Dame de Paris on fire, April 15, 2019 at 21:21. Photo credit © Baidax, Wikipedia.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

This ends months of speculation that the spire would be rebuilt in a modern style. Macron himself had previously favored a contemporary design.

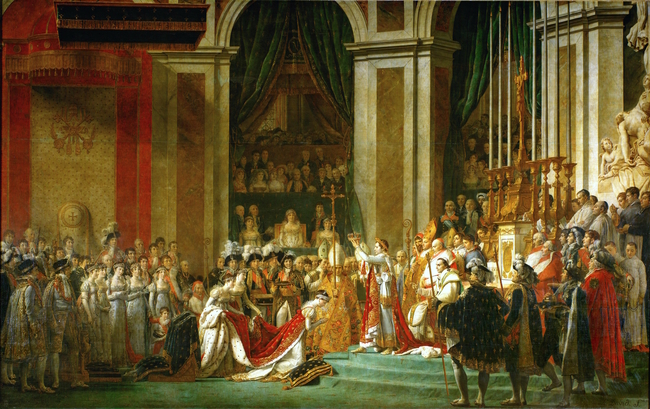

Two historical characters that had diverging opinions on Notre Dame’s appearance were the renowned writer Victor Hugo, and neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. In Hugo’s camp was Quasimodo, in David’s, Napoleon Bonaparte. The cathedral Victor Hugo portrayed in Notre-Dame de Paris published in 1831, and the cathedral David painted for Napoleon’s 1804 coronation were different spaces not far apart in time, yet the atmosphere they created for this sacred space couldn’t be more different. Comparing Hugo’s depiction of Notre Dame and its protagonist to Jacques-Louis David’s Coronation of Napoleon and its main subject, it is evident that both of these anti-monarchists were after change, but change meant different things to these two creators.

The Notre-Dame de Paris interpreted in Jacques-Louis David’s painting The Coronation of Napoleon (1807) was a cathedral changed in his imagination from a gloomy, gothic space into a bright, illuminated one. This represented the neoclassical style popular in David’s day. Napoleon, the painting’s central figure, was portrayed as a demigod as he crowned his wife Josephine as Empress.

Joséphine kneels before Napoléon during his coronation at Notre Dame. Behind him sits pope Pius VII. Photo credit © Jacques-Louis David, Wikimedia.com (public domain)

Although Republicans were supposedly enlightened and forward thinking, they adhered to the prevailing artistic style, neoclassicism, which invoked the civilizing virtues found in the art of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) had painted the interior of the cathedral as bright and polished, with painterly treatments and marble on the walls. David visually flattened the actual ornate and rounded gothic columns into popular neoclassical arches. The coronation setting was swagged with blue velvet curtains dotted with the fleur-de-lys. The Napoleonic “N” on the pelmet attested to the fact that Napoleon considered himself more important than the Church. Absent were the height and the soaring buttresses that define gothic architecture. David kept the activity grounded and focused on Napoleon. A ray of futuristic light shone down upon the exaggerated figure of the Emperor. The crowd seemed warm on that chilly December date.

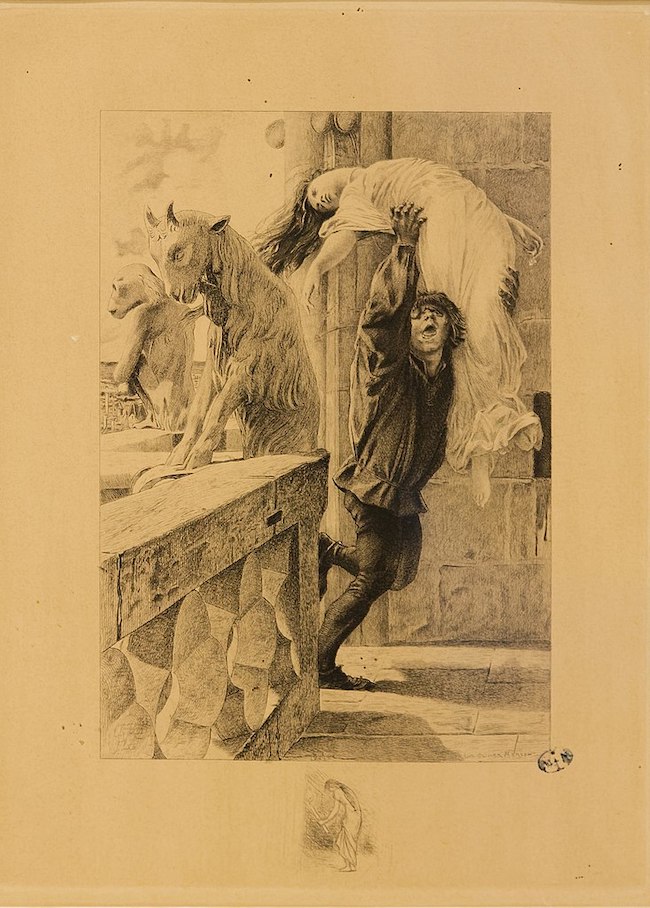

David’s Notre Dame does not seem like the same church that Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo crept about as a reptile on the dank pavement among the grotesque shadows thrown by the pillars. The reason is an about-face to a period of Romanticism.

Luc-Olivier Merson – Illustrations from the novel Notre Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo. Exhibition “Luc-Olivier Merson illustrator and decorator” at the Nantes Arts Museum (March 16 – June 17, 2018). Photo credit © François de Dijon, Wikipedia.com (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Time and turmoil passed and by 1830 Parisians found they were in need of rehabilitation. The July Revolution had battered the city. Years of Napoleonic aggression and administrative tumult had left them with their ideals shattered. Was France a republic, an empire or a monarchy? They needed a new definition of French society. Enlightened rationality stemming from the French Revolution gave way to the wildness of Romanticism. Yearning for a simpler time, the Romantics also looked to the past for inspiration. Using words like revival, regeneration, and restoration, they did not want to innovate; they were looking backward for primitive ideologies and forgotten origins, even reveling in the grotesque.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) French poet and novelist, was the hero of the Romantics and their salons. Completed on January 25, 1831 his Notre-Dame de Paris revealed the Notre Dame of the past, set firmly in the 15th century with protagonist Quasimodo personifying a simpler time.

Bonjour Paris writer, Hazel Smith’s geometric interpretation of the Notre Dame, on a beautiful day. Photo credit © Hazel Smith

On the evolving change in appearance of the cathedral of Notre Dame, Hugo wrote, “fashions have done more mischief than revolutions,” and that contemporary trendsetters “have impudently clapped upon the wounds of gothic architecture their paltry gewgaws of a day, their ribbons of marble, their pompons of metal…draperies, garlands, fringes.” This seems like a deliberate rebuttal of J.L. David’s festooned coronation which illustrates Hugo’s complaint about fashions of the day. Hugo went on to judge that, “the new art takes the structure as it finds it, incrusts upon it, assimilates itself to it, proceeds with it according to its own fancy.” As we know, Jacques-Louis David took the gothic Notre Dame and changed its architecture to suit his admiration of the neoclassical.

Quasimodo’s beloved Esmeralda witnessed the cathedral as “vast, gloomy, hung with black, dimly lighted…opening like the mouth of a cavern…” whose “gloomy façade wore such a strange and sinister air that the grand porch seemed to swallow the multitude.” Jacques-Louis David’s cathedral did not resemble this church at all. David had transformed Notre Dame into a warm, welcoming place of celebration. Victor Hugo switched Notre Dame back into a dreary place. Victor Hugo promoted the grotesque. The grotesque was fashionable with the Romantics and Salonistes as it represented a change to get back to one’s roots.

Napoleon, without question, was eager to take the spotlight. Quasimodo preferred the shadows. David represented Napoleon as larger than real life, standing straight, clean, and luxuriously clothed. The hunchback Quasimodo is a shadowy, misshapen form dressed in rags. Depicted in David’s painting of Napoleon’s coronation are many notable people. Despite the throngs of people represented, there was even an element of deceit as David depicted people that were not in attendance. To Quasimodo all would have been interlopers in his home. The statues within the cathedral were his people. “It was peopled with figures of marble, with kings, saints, bishops who at least did not laugh in his face…” wrote Hugo. The demons bore their malice upon other men. The saints and monsters were Quasimodo’s only friends.

“The Church of Notre Dame at Paris is no doubt still a sublime and majestic edifice. But, notwithstanding the beauty which it has retained even in its old age, one cannot help feeling grief and indignation at the numberless injuries and mutilations which time and man have inflicted on the venerable structure” wrote Hugo. Jacques-Louis David embraced the ideology of the Enlightenment. He had infused Notre Dame with light and changed it into a bright, warm space. Victor Hugo, looking for his roots, took Notre Dame back to the Middle Ages by changing it into a grotesque edifice.

It seems that Notre Dame is no stranger to danger, decay, renovation and repatching. The cathedral has survived for another day and will no doubt be tested again. As long as people love the idea of the cathedral– be it for religious reasons or civic– Notre-Dame de Paris will survive, albeit with a few more bandages.

Lead photo credit : Notre-Dame. Photo credit © Stefaan, Pixabay.com

More in Notre Dame cathedral, Notre Dame de Paris, victor hugo