Jacques-Louis David: A Sign of the Times

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Before there were cameras, film, video, mobile phones, and instant Internet downloads to record the course of human events, we had painters. And France in the years spanning the Revolution, the first Republic and the first Empire had Jacques-Louis David. He was the photojournalist of his time; his lens and keyboard were his eye and brush.

David came of age in the last years of France’s ancien régime. From the start, his work reflected the changing attitudes then rocking society’s foundations. He eschewed the Rococo frivolity epitomized by the architecture and court lifestyle of Versailles, preferring a classical manner of painting that upheld such values as patriotism, loyalty and self-sacrifice then being espoused by Enlightenment thinkers.

As a young man, David spent five years in Rome, copying the Italian masters amid ancient ruins. He found classical concepts “eternal” and returned to Paris in 1780 prepared to revolutionize the dictates of the Royal Academy of Art. Though his elders brushed him off as an opinionated upstart, his talent was impossible to dismiss. Indeed, after seeing David’s paintings in the Academy’s Salon of 1781, King Louis XVI granted him residence at the Louvre – then an exclusive artists’ studio.

Despite the royal honor, however, David did not sell out his Enlightenment ideals. His 1784 painting, Oath of Horatii, references Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “social contract”: that individuals create society by mutual consent, agreeing to abide by certain rules without their being imposed, and accepting the duty to protect one another. Central to the image, the three sons of Horatius pledge their loyalty to Rome before heading into battle with the support of their father who provides their weapons.

Despite the royal honor, however, David did not sell out his Enlightenment ideals. His 1784 painting, Oath of Horatii, references Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “social contract”: that individuals create society by mutual consent, agreeing to abide by certain rules without their being imposed, and accepting the duty to protect one another. Central to the image, the three sons of Horatius pledge their loyalty to Rome before heading into battle with the support of their father who provides their weapons.

Although the king believed the painting to be an allegory about allegiance to state – and therefore monarchy – the public read a more communitarian message into the painting and it swiftly became a symbol of the coming revolution.

Two years before the Revolution’s outbreak, in 1787, David unveiled his famous Death of Socrates. There was no mistaking the message here. It represents the last moments in the life of the Greek philosopher, condemned to exile or death by the Athenian government for teaching skepticism and thereby corrupting the minds of youth. Pointing up to the heavens in fearless defiance as his colleagues and disciples despair, Socrates chooses self-sacrifice over self-censorship. He drinks the poison hemlock.

Two years before the Revolution’s outbreak, in 1787, David unveiled his famous Death of Socrates. There was no mistaking the message here. It represents the last moments in the life of the Greek philosopher, condemned to exile or death by the Athenian government for teaching skepticism and thereby corrupting the minds of youth. Pointing up to the heavens in fearless defiance as his colleagues and disciples despair, Socrates chooses self-sacrifice over self-censorship. He drinks the poison hemlock.

Not coincidentally, this painting was commissioned by the Trudaine de Montigny brothers, leaders in the call for greater public participation in France’s political and economic affairs.

With Socrates, we see David amidst the gathering storm of discontent soon to rain down upon France’s hereditary aristocracy and corrupt Church. But it isn’t until the Revolution is officially underway that David sheds the use of classical allegory in favor of depicting real-time events. No longer merely the pundit, he is now the “photojournalist” – or, as he was known in his day, the creator of “history painting”.

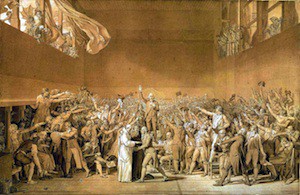

His Tennis Court Oath commemorates the birth of the National Assembly. Its members raise their right hands in a collective pledge not to disband until they’ve written France her first Constitution. At the center, three figures denote the enlightened noble, clergyman and every-man, joining forces to lead France toward a just future. Outside, fierce winds blow like the people’s fury with the old regime, sending gusts into the Versailles jeu de paume where the event actually took place.

His Tennis Court Oath commemorates the birth of the National Assembly. Its members raise their right hands in a collective pledge not to disband until they’ve written France her first Constitution. At the center, three figures denote the enlightened noble, clergyman and every-man, joining forces to lead France toward a just future. Outside, fierce winds blow like the people’s fury with the old regime, sending gusts into the Versailles jeu de paume where the event actually took place.

Commissioned by the Society of Friends of the Constitution, the Tennis Court Oath propelled David front-and-center into the political arena. But the unity it portrayed was not to last, just as the painting would remain unfinished. By 1792 the Society had radicalized, split from Assembly moderates who favored constitutional monarchy and become the party of les Jacobins.

David joined the Jacobins, who stood for the total abolition of monarchy and Church. As their Propaganda Minister he succeeded finally in radicalizing the arts and became the group’s official party planner (read: chief rabble rouser), organizing festivals to celebrate revolutionary heroes and milestones that echoed in ritual and symbolism the pagan festivities of yesteryear.

By June 1792, the Reign of Terror was picking up speed and David was helping to pilot the train. Louis XVI and his family attempted to flee France. They were caught, arrested and brought back to Paris. In December, David voted with Maximilien Robespierre and Jean-Paul Marat to take the king’s head.

July 1793: Marat met his end at the hands of Charlotte Corday. Corday blamed Marat, a radical journalist, for the death of the true Revolution and the growing Reign of Terror. In perhaps the most famous painting – and funeral procession – of his career, David immortalized the event, turning Marat into a martyr. The Death of Marat has been called the Pietà of the Revolution. With it David likens Marat to a fallen Christ figure, wielding a pen at the service of the people while dying by a knife-wound inflicted by one of its own.

July 1793: Marat met his end at the hands of Charlotte Corday. Corday blamed Marat, a radical journalist, for the death of the true Revolution and the growing Reign of Terror. In perhaps the most famous painting – and funeral procession – of his career, David immortalized the event, turning Marat into a martyr. The Death of Marat has been called the Pietà of the Revolution. With it David likens Marat to a fallen Christ figure, wielding a pen at the service of the people while dying by a knife-wound inflicted by one of its own.

The Reign of Terror continued until 1795 when the political winds shifted again and the leadership began to turn on itself. David escaped execution thanks to the intervention of his estranged wife, a former royalist who left him when he voted to execute the king. She convinced him to make amends to his countrymen through that which he did best: painting.

With Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799, David returns to storytelling through classicism, imploring the French people to reunite after the bloodshed of Revolution. The work saved David’s life. It restored his marriage. It caught the attention, as well, of a rising young General…

David and Napoleon were intrigued with each other from the start. After his coup d’état in 1799, First Consul Napoleon commissioned David to render him “calm upon a fiery steed”. The result: Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Following his second coup d’état in 1804, Emperor Napoleon had David depict his coronation in grand format.

When the Emperor’s star finally fell in 1815, court painter David chose self-exile. He died in Brussels in 1825. His body was not allowed to return to France due to David’s crime of regicide. This is itself a sign of the times, given the monarchy was again in power. One wonders if a different decision might have been taken under Napoleon or a French Republic. Indeed, David’s heart finally made it back to Paris. It can now be found at the cimetière Père Lachaise.

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

More in Bonjour Paris, France, French history, Museum, Paris art museums