The Mystery of Leon, Édouard Manet’s Son

In 1849, Suzanne Leenhoff was employed by the wealthy, bourgeois Manet family to teach their sons Édouard (aged 17) and Eugène (16), the piano. Why Leenhoff, then herself only 19 years old, left Zaltbommer in Holland and traveled alone to Paris is not known. Suzanne was known to be deeply religious her entire life, so giving birth to an illegitimate son less than three years later was at odds with all her beliefs. The birth certificate cited the child’s name as Leon Édouard Koella. (Koella was suspected to be an invented name.)

When baptized in 1855, Leon became known as Suzanne’s younger brother and Leon believed this to be true until he was twenty years old. Even when Édouard married Suzanne in 1862, she insisted that Leon was still to be known as her brother and only legally acknowledged him as her son just before her death in 1906 to ensure his inheritance.

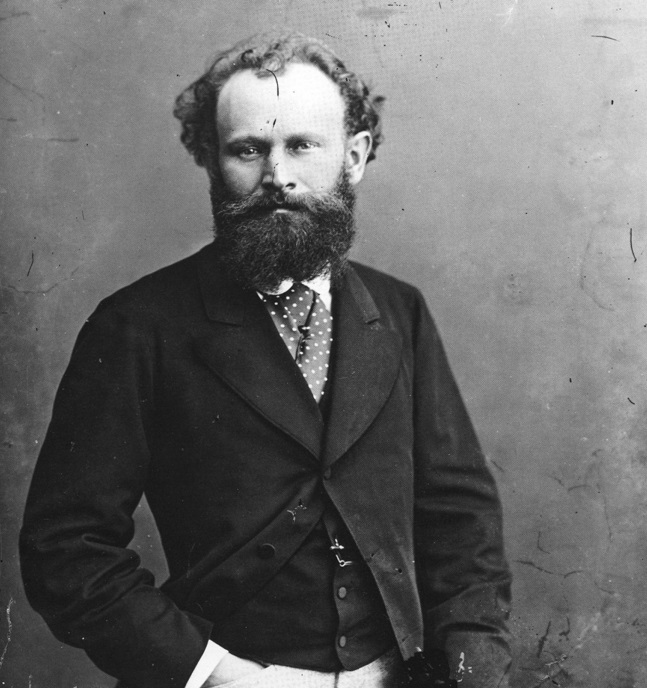

Édouard Manet, by Nadar, Wikimedia.

(Édouard, on his part, never publicly acknowledged Leon as his son although this was common practice at the time, especially among artists liable to have one or more illegitimate offspring.)

With her religious beliefs, it is easy to understand Leenhoff’s shame at giving birth out of wedlock, what is harder to fathom is the distinct possibility that she was both Édouard’s mistress and also mistress to his father Auguste Manet. Which of course begs the question: If Leenhoff was also the mistress of Auguste, then Auguste was just as likely to be the Leon’s father as Édouard.

The respected art critic Waldemar Januszcak believed that not only was Auguste the real father of Leon, but was also the influence behind Manet’s most iconic painting, Déjeuner sur L’Herbe. This was the painting that scandalized Paris in 1863: the brazen nude lolling outdoors in a park between two fully clothed gentlemen.

Déjeuner sur L’Herbe by Édouard Manet.

Januszcak maintains this was Manet’s response to his own, personal experience and his disgust at the thin veneer of respectability, lust and above all hypocrisy that he had found not only in French society but also in his own family.

Auguste Manet was indeed the epitome of the respectable, middle/upper class establishment. He was a senior judge at the Palais de Justice and a holder of the Legion d’Honneur.

Portrait of M. and Mme. Auguste Manet by Édouard Manet.

Born in 1796, he was a strict father who had never wanted Édouard to be an artist. (His capitulation in his son’s choice of career has been cited as another pointer that Manet senior had something to hide.)

Auguste died of tertiary syphilis– a disease he had certainly not contracted from his wife. (Édouard’s mother Eugénie-Desirée Fournier was herself not only the daughter of a diplomat but also the goddaughter of the Swedish Crown Prince Charles Bernadotte.)

In 1857 Auguste suffered a form of paralysis and although he regained his ability to walk again after several months, his intellectual abilities were so compromised he was forced to retire as a judge. He died in 1861, a year before Édouard married Suzanne. (Some art historians believe this another pointer towards Auguste being Leon’s father– that Édouard waited until after Auguste’s death to marry Suzanne. He could of course, just have been waiting for his inheritance to be settled.)

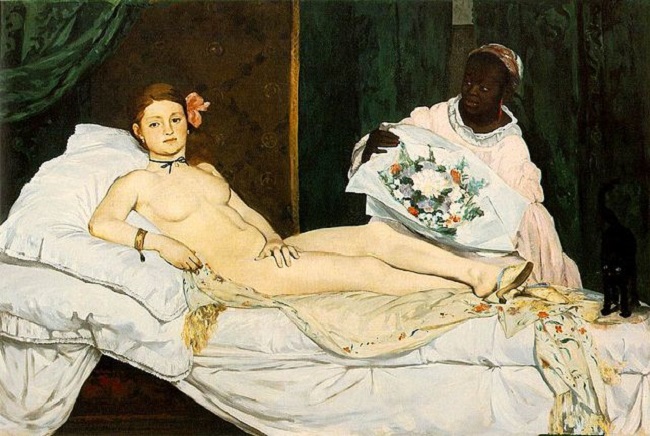

Manet continued to shock with his uncompromising paintings. Again in 1863, Manet exhibited his Olympia.

Olympia by Édouard Manet.

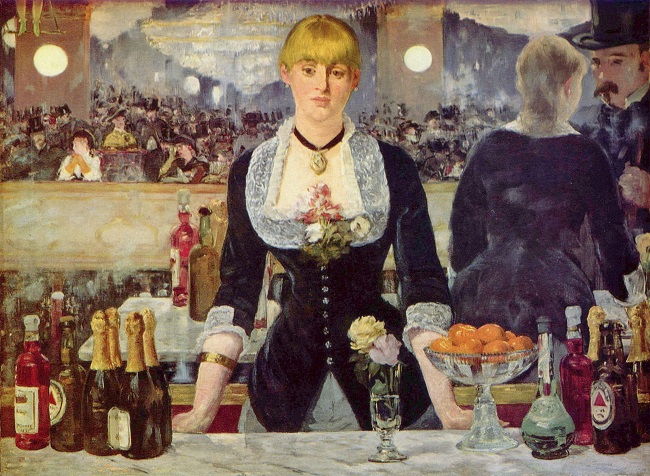

Based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino, Manet’s interpretation depicts Olympia as a prostitute; in fact Olympia was a well known name associated with prostitutes in 1860s Paris. In Manet’s Bar aux Folies Bergères, the hauntingly sad face of the barmaid suggests she is expected to serve more than alcohol to her clientele.

Suzanne often modeled for Édouard; however it was Leon who posed most for Manet. From an early age, Leon had featured in Manet’s paintings, 17 in all from Boy with a Sword in 1861 to Interior at Arcachon in 1871. Almost all the paintings featuring Leon including A young man peeling a Pear 1868, Boy Blowing Bubbles 1867 and perhaps the most inscrutable, Luncheon in the Studio 1868, portray Leon as serious, without emotion– a figure somehow detached from everything around him. Only The Boy with Cherries depicts the blonde, pale faced Leon smiling.

Luncheon in the Studio is an intriguing study with more questions than answers. Is the maid Suzanne? Is the bearded man Manet or his father? Only Leon stands up front aloof, his expression without much warmth or evident personality.

Bar aux Folies Bergères by Édouard Manet.

Manet never seemed to imbue paintings of Leon with any kind of sympathetic characteristics. Leon is a mysterious almost bland figure and perhaps not the kind of portrait a loving father would be expected to paint.

Compared, say, to Manet’s compelling portrait of Berthe Morisot and indeed the emotive barmaid in the Folies Bergère, Leon remains inscrutable, impossible to fathom beyond his cool gaze. (It was Berthe Morisot who influenced Manet to plein air painting and to using a lighter palette. Later she married Eugénie, Manet’s brother and became Manet’s sister-in-law.)

Luncheon in the studio by Édouard Manet.

Suzanne, although often used as a model for Manet, was not part of Manet’s often hectic social life seldom, appearing at parties which even after their marriage, Manet’s mother hosted. Manet, handsome and filled with bonhomie, was the antithesis of Suzanne who was quiet, matronly and unassuming but known to be a kind if placid wife. It may be that her secrets affected any desire to share in the limelight of her husband.

Manet’s work encompassed a whole range of subjects: depictions of war, still life, but perhaps his most loved were his paintings of café scenes in Paris. Manet often frequented the Cabaret de Reichshoffen on the Blvd Rochechouart, Pigalle where his observations of rich, middle class gentlemen mixing with women on the fringes of society, only confirmed his views on the double standards of the time.

Manet’s health began to deteriorate in his mid forties. Like his father before him, Manet suffered partial paralysis in his legs. Believing it to be a circulatory problem, Manet had hydrotherapy treatments at a spa near Meudon. Sadly, like his father, Manet was also suffering from syphilis– locomotor ataxia being a side-effect of the disease. In 1883, Manet’s left foot was amputated because of gangrene, another complication of syphilis. He died eleven days later in Paris on April 30, 1883 and was buried in Passy Cemetery.

Suzanne, as instructed by Manet, left all his paintings to Leon on her death in 1906.

Leon died in 1927. He had married but was childless. The mystery of his true father never to be known.

What we do know though is that Leon was a businessman, unconnected to the art world of his father and seemingly disinterested, apart from in a financial way, to his father’s legacy.

The paintings he couldn’t sell, he burned.

Perhaps in this last, unsentimental gesture, Leon had the last word.

Cabaret de Reichshoffen by Édouard Manet.

Lead photo credit : Suzanne Leenhoff and her son Leon Leenhoff, by Édouard Manet.

More in art and culture, artist, Manet

REPLY