Left Bank Lesbians in 1920s Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The end of World War One, the devalued franc, and the ever enduring beauty of Paris, along with the lure of a bohemian lifestyle in a city known for its tolerant attitudes, led not only to an influx of American writers, poets, artists and musicians, but also to a group of rich or independent women who had eschewed the status quo and respectable expectations of their families.

Only Berlin could hope to compete with Paris with its gay clubs and newspapers and even a lesbian magazine, Die Freundin.

In New York, even in Greenwich Village, lesbians although tolerated were generally misunderstood even amongst the much larger homosexual community who had made their homes there. The rest of America was even less understanding.

Less tolerance still, was to be found in England. In 1921 a Member of Parliament proposed the clause, ‘Acts of Gross Indecency by Females’ to be added to the criminal law amendment act of 1885, which had been passed against male homosexuals. He stated that lesbianism debauched young girls, induced neurasthenia and insanity. There was unanimous agreement and the amendment was passed up to the House of Lords for ratification. However the Lord Chancellor asserted that 999 women out of 1000 had never heard a whisper of these practices and therefore this ‘noxious and horrible suspicion must not be imparted.’ The bill failed.

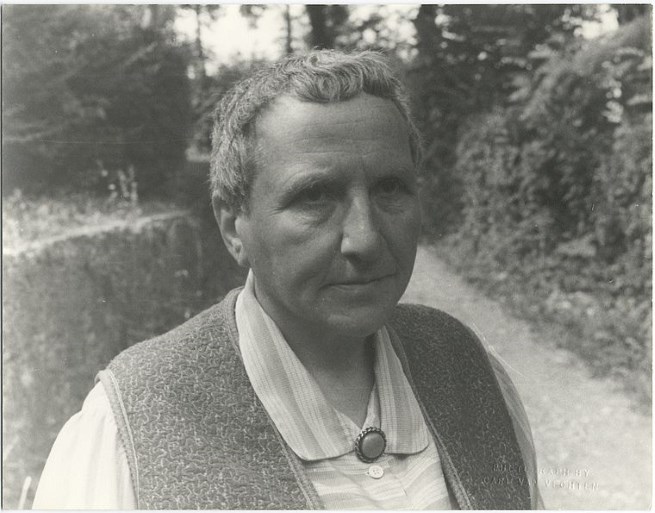

Gertrude Stein, photo: Carl Van Vechten/ Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Later in 1928 when Radclyffe Hall published The Well of Loneliness, the public prosecutor stated that he would rather ‘give a healthy boy or a healthy girl, a phial of prussic acid, than this book.’ (The book featured a thinly disguised Natalie Barney.)

Hardly then, a great endorsement for lesbians to come out in England…

The attraction of Paris for avant-garde, liberal, free thinkers and those whose sexual preferences would be in the main ignored or tolerated, proved irresistible to a group of disparate women, lesbians and bisexuals who made their mark on Paris in the 1920s as in no other decade, before or since.

There were the famous monogamous couples: Gertrude Stein, the writer and art collector and her lifetime partner, Alice B Toklas, who lived first in the Rue de Fleurus, just off the Luxembourg Gardens, then later on Rue Christine.

Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier, with their bookshops almost opposite each other in Rue de L’Odeon-Shakespeare and Co and La Maison des Amis des Livres, lived together harmoniously until Adrienne’s death in 1955.

There were others not so monogamous, but all were linked in one way or another to Natalie Clifford Barney and her salon at 20, Rue Jacob in the heart of St Germain.

Natalie Barney was born in Dayton, Ohio in 1876 into a wealthy family and was educated at Les Ruches, a French boarding school near Fontainebleau. Her French was consequently fluent and without accent. Most of Barney’s books and poems were published in French.

Natalie Clifford Barney

(Here it would be impossible not to mention Barney’s mother, Alice Pike Barney, who insisted both her daughters were educated in France and was the forerunner of Natalie’s salon in the Rue Jacob, by opening her salon in 1899 in Avenue Victor Hugo. In 1882, Alice and Natalie had spent the day on the beach with Oscar Wilde after seeing him speak at New York’s Long Beach hotel in 1882. The encounter was to change Alice’s life and she was persuaded to take her painting seriously for the first time in an era when women painters were considered automatically inferior. Her paintings can now be seen in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and it would require another article to even scratch the surface of the life of this amazing woman.)

Natalie had known she was a lesbian since she was 12 years old and in 1899, aged 23, had a brief affair with the courtesan Liane de Pougy who was appearing at a dance hall in Paris. Later she lived in Lesbos with the poet Renée Vivien. It was in 1909 that she finally rented the house in Rue Jacob. The house had the added attraction of a garden which boasted a Doric ‘temple of friendship.’ (After Barney died a secret tunnel was discovered in the garden. The tunnel led down to the Seine.) The garden and the temple were an integral part of Barney’s Sappho gatherings where sometimes guests dressed as wood nymphs or simply naked, danced in the courtyard garden until dawn. It was the perfect setting for Isadora Duncan in her Greek tunic. Mata Hari was reputed to have ridden naked through the courtyard on her favorite horse.

By the 1920s Barney had established her ‘women’s academy’, the Academie des Femmes, and her salon not only attracted lesbians but also the artistic and intellectual of the time. Regulars included Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Anatole France, Sherwood Anderson, Colette (a one time lover of Barney), Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sylvia Beach, Peggy Guggenheim and Isadora Duncan (famously bi-sexual)– to name but a few.

Barney’s main long-lasting relationships were with Romaine Brooks (who was her lover for 50 years), Renée Vivien, Élisabeth de Gramont, and Dolly Wilde, Oscar’s Wilde’s niece. Barney refused to practice monogamy, often running three affairs simultaneously, to the disregard of the subsequent heartbreak of many of her lovers, especially Dolly Wilde.

Marion ‘Joe’ Carstairs, photo: Wikimedia commons

Dolly Wilde, who looked amazingly like her uncle Oscar, came to Paris in 1914 to drive ambulances on the front line. An ethereal looking creature with great charm, she adored working with the extraordinary women she met in the ambulance corps -one in particular was Marion “Joe” Carstairs, an oil millionairess who usually dressed as a man and had affairs with many famous women including Marlene Dietrich. Most of Dolly’s companions wore trousers, smoked and took women as lovers. The fashion of Chanel with her androgynous, short haired models set a new fashion trend, perfect for lesbian society.

Dolly was a natural for Natalie Barney’s salon. Unfortunately for Dolly, she fell disastrously in love with Natalie who became the love of her life. Sadly, Natalie, though extremely fond of Dolly, was never made to be faithful and often continued affairs with other women even when Dolly was living in her house. Dolly drank heavily and acquired a cocaine habit, was often strapped for funds and supported financially by friends. She died, estranged from Barney in 1941.

Annie Winifred Ellerman, another visitor to Barney’s salon, who was better known as Bryher, was born in Margate in 1894, the daughter of John Ellerman a shipowner and financier. (In 1933 he was stated to be the richest Englishman who had ever lived.)

Bryher’s circle of friends in Paris included Hemingway, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein and Sylvia Beach who she helped financially when Shakespeare and Co was going through hard times. Bryher decided on a marriage of convenience to the American writer Robert Almon who she married in 1921, although she had already fallen in love with the poet Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) in 1918. Bryher and Almon divorced in 1927 and Bryher married a writer Kenneth MacPherson who was H.D.’s lover… The ménage a trois lasted until 1947 when MacPherson died and although no longer living with H.D, Bryher’s relationship lasted with her until H.D.’s death in 1946.

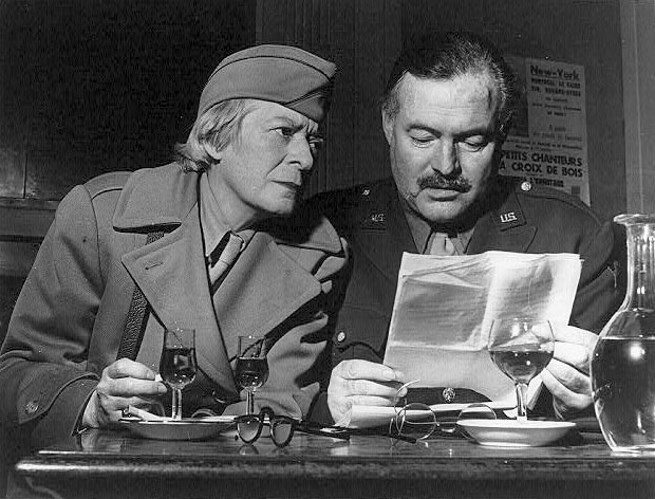

Those women who did not have a fortune at their disposal, including Sylvia Beach, who worked hard as independent women, included the renowned American journalist and writer Janet Flanner.

From 1925 until 1975 she was the Paris correspondent for the New Yorker magazine. She was also married… to William ‘Lane’ Rehm. (The convenience of this marriage, Flanner later admitted, was to get out of Indianapolis!) But, in the same year as her marriage (1918), she had already met the artist Solita Solano, who became her life-long lover, although neither of them were faithful to each other.

Flanner and Hemingway working as War correspondents for the Liberation of Paris, See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

However all lesbian and bi-sexual life in Paris were not based on common intellectual or artistic interests. Parisian nightlife embraced diverse sexualities with open arms.

Many of these clubs, or bal musettes, were based in Montmartre or Pigalle, but the Left Bank was not to be left out.

High on a hill behind the Pantheon, the Bal de la Montagne- Sainte-Geneviève was a favorite haunt of homosexuals and lesbians. While the police turned more or less a blind eye to it, men dancing together was still frowned upon. Here, the women came in handy as during a police raid, they would simply swap partners with the men.

But the best lesbian club was still to be found in Montparnasse. In the 1920s, Le Monocle opened in Boulevard Edgar Quinet. The majority of women (even the hat check girl) dressed as men in tuxedos with their hair bobbed and slicked back. Monocles, a Sappho sign, were worn with aplomb. Lady Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall were rarely seen without one. The writer Colette, visiting Le Monocle, noted that the ‘mannish women’ often affected a monocle with a white carnation in the lapel of their tuxedo jacket.

Lesbian couples in Le Monocle, photo: Brassaï

Whilst Le Monocle lasted until the early 1940s, the 1930s were already bringing in the winds of change. In Berlin, the Nazis closed all Berlin’s gay and lesbian bars. In Paris, the intense and sometimes hedonistic free living of ‘Les Années Folles,’ as the 1920s were known, was never again to be completely repeated or replicated. During this decade, the French economy had boomed and Paris had become an intellectual breeding ground for all the arts. The Great Depression heralded a more sombre, cautionary note of hardships to come.

The 1920s had been a unique era in the history of Paris. After the horrors and deprivations and darkness of World War 1, where better to seek new freedoms, new inspirations than in Paris, the City of Light?

Lead photo credit : Natalie Barney, Janet Flanner and Djuna Barnes, wikimedia commons

REPLY