French Film Review: Et Les Mistrals Gagnants

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

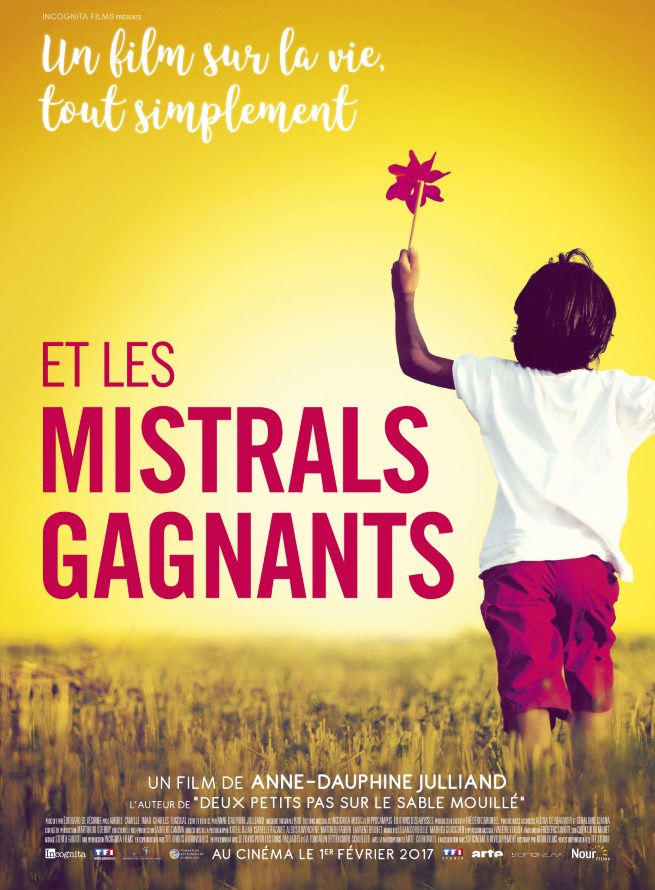

Et les Mistrals gagnants

The most acclaimed French film at the moment, and one of the most moving in years, is a documentary, Et Les Mistrals Gagnants. It’s one of those films whose making-of backstory is so intertwined with the work that it seeps into one’s perceptions. Anne-Dauphine Julliand, the director, is a neophyte at film-making. For years she worked as a journalist, but then two of her children fell victim to a rare genetic disease. She lost one child. The battle and heartbreak led her to an affirmation of her faith and the writing of a book which became a critically praised bestseller, Deux petits pas sur le sable mouillé (literally “Two little footprints on the wet sand”—she’d noticed something amiss with her children when they walked strangely on the beach). Then her second child also died.

Afterwards, she became interested in the struggles of other families and their suffering children. Et les Mistrals Gagnants follows five children as they deal with severe illnesses. The film is realistic and sometimes scarifying, but while not sentimental, it doesn’t shy from sentiment, and is affirmative and uplifting throughout.

The five children come from different backgrounds, but all are between the ages of 6 and 9. They suffer from different problems, and don’t seem to know one another or come into contact, though much of the action takes place at one hospital, the Hôpital Robert-Debré, in northern Paris. Imad has a kidney problem, and must undergo uncomfortable dialysis while waiting for a transplant. Ambre has life-threatening heart disease. Charles, has a disorder which leaves his skin painfully sensitive. Camille suffers from neuroblastoma, a cancer of the nervous system. Tugdual has a large tumor lodged in his aorta.

The film lets the children speak for themselves, without questioning or prodding. Otherwise we see them undergoing treatment, playing, participating in sports and theatre, interacting with family, trying the best they can under the circumstances to get an education. The sicknesses aren’t spelled out, except to the degree that a doctor tries to explain to his young patient. Mostly we see the medical professionals doing their jobs in a competent and caring way. There’s no talking-head aspect to this. Likewise, we occasionally see the parents taking care of their children, or interacting in a general way. There’s no explaining or special pleading from the parents, no mention of their own travails. The film is resolutely about our five intrepid children.

One might carp that all the children are cute and photogenic—the sort of criticism levelled at telethons featuring sick and handicapped children as “poster kids”. But then Denzel Washington and Nathalie Portman are photogenic as well, and they’re still great actors. The children aren’t only cute, but courageous, witty, stoic, and bright. Imad especially is amazingly precocious and yes, an audience pleaser, a modern-day Shirley Temple minus the cloying corniness.

In any case, the movie doesn’t seem to be mainly about fighting for one’s young life, or maintaining a decent quality of life, although these are implicit. It has more to do with living life with whatever’s been allotted to you, fighting the good fight but also appreciating the pleasures, joys, and love of others. It’s an attitude some might call zen or existentialist (of a religious variety). The filmmaker’s outlook may be more Catholic, in a French humanistic way, though we only observe one of the families praying in a mountainside chapel, not to mention that one of the children, Imad, is from a Muslim family.

Et les Mistrals gagnants

Technique may be beside the point in a film like Et les Mistrals Gagnants, but it’s worth noting that it’s cleanly, soberly shot throughout, in a way that recalls Panavision rather than digital. The close-ups are affecting but unobtrusive, the more “dynamic” shots smoothly integrated into the film. The first-time director was clearly aided by a very skilful team of cinematographers and editors. Towards the end of the film she indulges in shots of flowers and such like, but they’re not jarring, and we feel after all the children have been through, the mini-epiphanies have been earned.

In addition to being talented, the technicians apparently bonded very strongly with both Julliand and the children. The solidarity involved in the making of the film extends to its financing. Julliand depended to a very great extent on a crowdfunding outfit called KissKissBankBank. In the credits after the film we see the many names of people who contributed to its production.

Even the title of the film has a special back-story. It comes from a song, “Mistral Gagnant”, by Renaud, France’s Dylanesque bard of social protest. The mistral gagnant was actually the name of an old-time candy. Renaud sings hauntingly of the sweets of his childhood, of which the mistral gagnant, that have all but disappeared. Though the song is a classic of melancholy, it inspired an organization dedicated to helping children with rare “orphan” diseases, that don’t receive much attention (or funding for research). Julliand was in turn also inspired by Renaud (who also served as the organization’s patron). When we hear his wistful rasp singing “Mistral Gagant” at the movie’s conclusion, we feel something has come full circle.

Production: Incgognita Films

Distribution: Nour Films

Lead photo credit : Et les Mistrals gagnants