The Other Fontainebleau

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

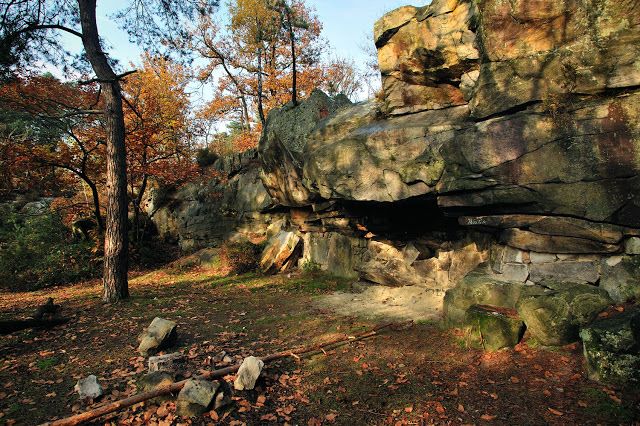

He introduced himself as “Pepito.” Sixty-something and lanky, with shoulder-length grey hair and a sun-chiseled face, he’s a typical bleausard, one of that group of devoted climbers who seem to know the forest of Fontainebleau and its thousands of boulders by heart. Like the alpinists before him who came to “Bleau” to train for snowy summits and rocky peaks, his pastime is seeking out new routes over and around the boulders that freckle the 280-square-kilometer forest an hour’s drive south of Paris.

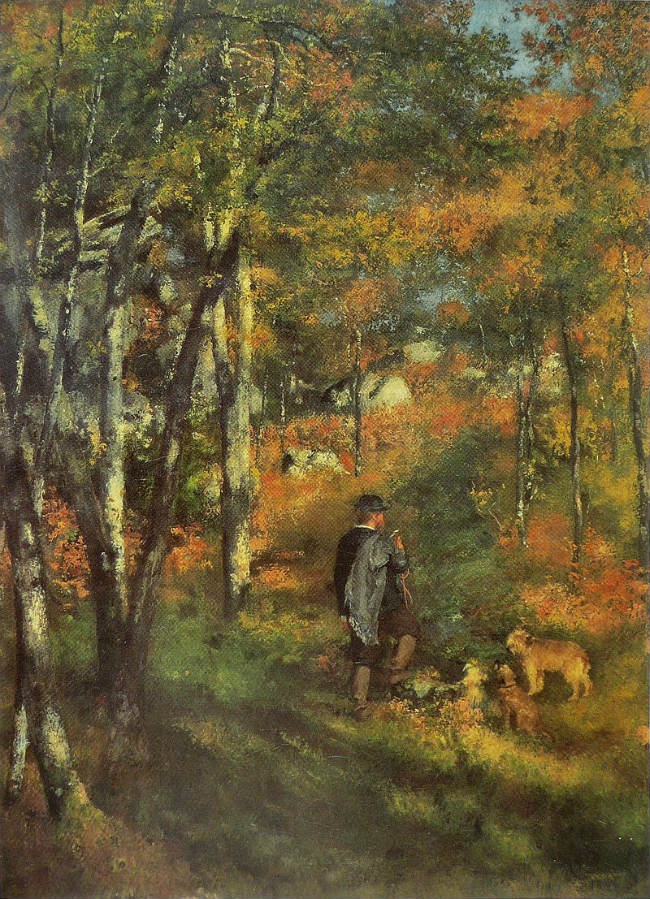

Over the centuries, the forest of Fontainebleau has inspired more than alpinists and sport climbers. When I met Pepito for a coffee in a south Paris neighborhood, he was on a rare visit to the city to pick up oils for his paintings — the town of Barbizon where he lives was the headquarters of The Barbizon School of French landscape painters who began flocking to Fontainebleau in the 1820s. Pepito is inspired by the same fern-encrusted gorges, ancient sands and sun-dappled oak trees that impassioned masters like Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet. Advocates of outdoor painting, even in the rudest winter conditions, they pioneered a new way of looking at and painting nature, long before the Impressionists shocked the world with their haystacks.

Personally, I go to Fontainebleau to rock climb and to get away from the grit and grime of Paris. On weekend afternoons, English, French, German and sometimes even Japanese voices drift up from between the sandstone monoliths to mingle in the warm sunlight. Couples, families and groups of friends stake out shady spots for their backpacks, tupperware picnics and the occasional hammock, then head off in search of the perfect “problem,” as bouldering routes are called.

But you don’t have to be a rock climber to appreciate this side of Fontainebleau. Telltale stripes and dots in blue, yellow and orange indicate hiking trails that wind hundreds of kilometers through the forest. One of the most famous, Les 25 Bosses, or The 25 Bumps, packs an unbelievable variety of landscapes into 16 kilometers: pine forests, moorish thickets of heather, boulder scrambles and a mer de sable, the remnants of an ancient sea that washed over the region 30 million years ago, leaving some of the world’s finest glassmaking sands in its wake. But Les 25 Bosses is not for the faint of heart: the trail’s 830-meter elevation gain (spread out over 25 hills) makes it popular with Paris-bound mountain climbers training for distant peaks.

Before it became a magnet for artists and climbers, Fontainebleau was a royal hunting ground. The towering oaks that once dominated the forest provided wood for the king’s building and heating needs in the nearby Chateau de Fontainebleau, which housed eight centuries of French royalty beginning in the 12th century. Over-exploited by the 18th century, Fontainebleau was the subject of several reforestation efforts. The sharp scent of evergreen that wafts through the forest today emanates from 14,000 acres of pine planted in 1830, much to the chagrin of the Barbizon painters.

The members of the Barbizon School weren’t the last to balk at developments in Fontainebleau. A closer look at the forest’s history reveals a trail of man-made conflicts, including the construction of the A6 highway that cleaved the forest in two in the 1960s. Recent years have seen a debate over drilling for shale gas in the south Seine-et-Marne, the region where Fontainebleau and dozens of small villages are located. And then there’s the ongoing struggle with illegal waste dumping in the forest.

Today there’s talk of giving Fontainebleau one of France’s many complicated variations on the title “National Park,” with environmentalists, sports enthusiasts and various interest groups throwing in their two cents. But perhaps more important than what we call the forest is how we interact with it: finding a balance between gentle observation and active participation. Next time I head to Fontainebleau, I think I’ll take a cue from Pepito and slip my paints in next to my climbing shoes.

Lead photo credit : The Fontainebleau Forest, courtesy of Tourisme Seine et Marne