Pierre Cardin: A Celebration of the Fashion Designer’s Life

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Whether he was designing spacesuits for NASA or showcasing extravagant bubble dresses at his luxury boutique on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, Pierre Cardin was celebrated by many Parisians and often regarded as the dictionary definition of futuristic. Even in his 90s he was still opening stores and museums – and he enjoyed such notoriety that at one point he valued his brand at $1 billion.

As we approach the one month anniversary of his tragic death, we take a look back at his life, career and, of course, his special relationship with Paris…

Life began amid wreckage and ruin but was improved immensely by the bravery of his migrating father. Cardin Senior fled the family’s native Venice after his career crumbled and he lost everything he owned to the ravages of the First World War. Once a successful wine merchant, he found himself surrounded by the fascist dictators who’d aided his demise – and so in 1924, with his wife and 11 children in tow, including two-year-old Pierre, he left home for a fresh start in France.

They first settled in Saint-Etienne, a short commute southwest of Lyon, and later in Vichy, where they would endure yet another World War. In his 20s, after a chance encounter with a psychic who predicted worldwide fame and recommended he tried his luck at the Paquin fashion house in Paris, Pierre Cardin ventured to the capital to find his own fortune.

Models for Pierre Cardin in 1966. Photo credit © Wikimedia Commons

His 1945 move to Paris held special memories for him as the timing marked the end of the war era and the beginning of peace and prosperity. He had suffered on his initial journey there when he was arrested and detained by suspicious Nazis en route, but as he was not of Jewish origin, his imprisonment was short-lived. Before long, the newly free Cardin found himself on rue Royale, eagerly seeking out the fashion house his fortune teller had suggested. He stepped through its doors to be met by the likes of Jean Cocteau and Jean Marais, whom he would join as they created costumes for the film Beauty and the Beast.

After working there, he subsequently joined the house of fellow Italian immigrant Elsa Schiaparelli – the arch rival of Coco Chanel – and then became a head tailor at Christian Dior. The only major brand to turn him down was Balenciaga, but that didn’t deter Cardin, who was scathing about big names he believed were superficial. “Anyone can’t draw is backed by money, is given a name…” he once declared. “I made it on talent alone.”

By 1950, encouraged by Dior, he was in a position to create his own self-titled brand. He began by designing 30 costumes for a Venetian masquerade ball but soon gravitated from theatre to haute couture fashion, which he sold in his boutique Eve, on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré. His “bubble dresses” – not theatrical costumes of the type made notorious by Lady Gaga, but dresses with fitted waists and contrasting flouncy, flared bubble hems – became a hit. Exaggerated baggy pantaloons with 3D circular shapes attached to them would also become one of his high fashion signatures.

A 1968 Pierre Cardin Dress. Photo credit © FIT Museum, USA. Wikimedia Commons

His presence in the world of womenswear could be controversial, however. During an era when designers dressed women to flatter, emphasize and accentuate the curves of their bodies – notably including his former employer Dior – Cardin chose to reject this philosophy. He preferred to see the female physique as a blank slate to embellish and openly admitted he found the fashion more significant than the bodies showcasing it.

“For me, the clothing is what counts,” he declared, offering the metaphor: “The body is like a liquid that takes the shape of the vase.”

To his detractors, however, this attitude was to the detriment of those who wore his clothes and when Jeanne Moreau – the only woman that “mostly gay” Cardin ever dated – donned the designs he’d made for her, the media dubbed them “unflattering” and “unsympathetic”.

He later turned his attention to male styles – and a huge career highlight was the moment when his first menswear collection hit the capital in 1958. According to Cardin, the Parisian fashion scene for men was non-existent at the time – and he was determined to fill the void. Some considered a love of chic tailoring to be emasculating and those that didn’t “went to London”, where the made-to-measure scene was thriving.

Cardin recalled how fastidious men had once been at the Palace of Versailles, where every lunch at its court had entailed dressing smartly, wearing makeup and meticulously fixing up hair. Yet the men of the era which he inhabited were totally disinterested in being chic.

“Why do the Italians and British design menswear,” he questioned indignantly, “and not the French?”

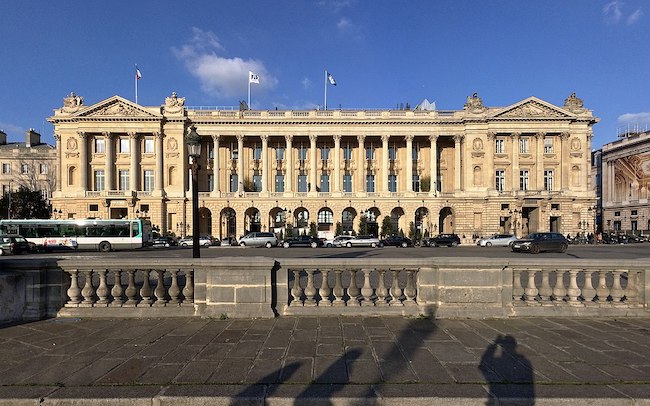

Not to be deterred, Cardin drafted in a group of local university students, the “faces of the future” and hit what he saw as Paris’s most prestigious address – the Hotel de Crillon on the Place de la Concorde. A royal residence since the 1700s and one of the very few French hotels to boast official ‘Palace’ status, it was steeped in history. The windows of this building had offered direct views onto the square back in 1793 as the guillotine blade came crashing down and sliced off Marie Antoinette‘s head. King Louis XVI had been murdered in the same location, as the crowds of the French Revolution era sought bitter revenge on the monarchy for its dominance.

Also, a little earlier in the same century, Benjamin Franklin had signed an historic document marking the recognition of the USA’s Declaration of Independence, so the reputation of this palatial hotel was almost unparalleled.

There was no location more dramatic for Cardin to make his own mark on history, as his models paraded modern, youthful styles intended to change men’s ambivalent attitudes to style forever. This was no longer the French Revolution, but the fashion revolution – and this time the crowds were not baying for royal blood, but peacefully applauding his designs. He later summarized proudly, “I completely overturned masculine fashion.”

Espace Cardin – Avenue Gabriel à Paris. Photo credit © Erwmat, Wikimedia Commons

Hilariously blunt about men’s looks as much as women’s, he once brazenly recommended the tuxedo for every man – “even if he is ugly, short or fat”! Meanwhile the ladies would be invited to try out astronaut-chic, with a Space Age collection eventually appearing. By 1970, he would even be invited by NASA to design “uniforms for the Moon” – and on a visit to its space station, he became the first civilian ever to have donned Buzz Aldrin’s spacesuit.

Cardin horrified some of his haute couture contemporaries by also diversifying into ready-to-wear collections for the middle classes – and was even suspended from a trade association because of it – but these looks were still coveted by everyone from the Beatles to Rita Hayworth. Plus by the 1960s, Cardin pioneered the trend for decorating clothing with the designer’s logo and name.

Over the years that followed, many commissions arrived, including design for a much-lauded national costume of Thailand, but Cardin enjoyed his work in France most of all. In 1971 he opened his own venue in Paris, the Espace Cardin, for both his own designs and the work of other artistic talents.

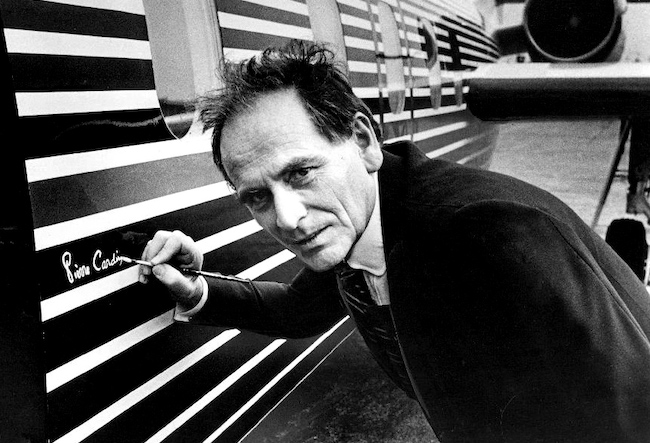

Eventually his fashion collections started to dwindle, but he diversified into furniture, perfume and restaurants (including Maxim’s), and arranged licensing agreements for an enormous variety of spin-off products – even ballpoint pens! He also designed car interiors and aircraft exteriors and delighted his father – who’d longed for him to become an architect since he was a young boy – by getting involved in the design of buildings as well.

The most famous one he’d ever been linked with was the Palais Bulles, his holiday home complex in Cannes consisting of extraordinarily futuristic liveable bubbles that looked like UFOs. The publishing company Assouline published a coffee table book dedicated to its unique architecture, simply titled The Palais Bulles of Pierre Cardin. Valued in 2017 at 350 million euros, it is typically used today for photoshoots and events, its most endearing feature being the 500-seat open air amphitheater offering spectacular Riviera views.

Yet Cardin wasn’t solely about the unusual and futuristic – other purchases included the crumbling ruins of a rugged Lacoste hilltop chateau once owned by Marquis de Sade. He has been photographed inside numerous times.

His licensing range continued to grow and extended even to sardines, but when he insisted with a totally straight face that he’d brand toilet paper if asked, it invited condescension from some critics. One 1989 article by the Economist joked that his signature had become as commonplace as that of the American Treasury Secretary – and “as devalued as the dollar bills he signed.”

Yet sarcastic snubs aside, he also won numerous awards for his prowess, including several ‘Gold Thimbles of French Haute-Couture’ presented by Cartier and in 1997 he was even made commandeur of the Légion d’Honneur. He would claim that his brand was worth $1 billion, although he ultimately never sold it.

Official portrait of Pierre Cardin. Photo credit © Claude-Iverné-Elnour, Wikimedia Commons

He remained active even into his 90s, as did a sister who tirelessly helped him run his business. In 2014, he inaugurated the new central Paris venue for his museum Passé-Présent-Futur, which featured hundreds of his haute couture designs (now closed). Subsequently in 2016 he became the first couturier ever invited by the Institut de France to present a dedicated fashion show at Académie des Beaux-Arts, titled “70 years of Creation“. He explained to those astonished at his business longevity, “Work is my life – my happiness!”

His shows have taken place everywhere from the depths of the Gobi Desert to the Great Wall of China, and he has traveled the world to meet everyone from Mother Teresa to Nelson Mandela, but the country that inspired his deepest love has remained France. The proud Parisian, who died aged 98 in the American Hospital of Paris in Neuilly-sur-Seine, declared: “I owe my success and the recognition of my talent to France.”

Pierre Cardin: 2 July 1922 – 29 December 2020.

Lead photo credit : Pierre Cardin signing an executive jet he designed 1978. Photo credit © Wikimedia Commons

More in designer clothes, Paris designers

REPLY