Four Influential Feminist Women in French History

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The French Revolution first proclaimed liberal and radical ideas and gave birth to the concept of feminism. However French women only gained the right to vote in 1944– a step that came many years after a number of other Western countries.

Yet numerous women throughout the history of France, whether politician, philosopher or artist, have contributed to the movement for women’s equality. Here I highlight the political or artistic trajectory of four women who lived at different times of history. All have been recognized for their individual achievements.

If you are learning French in Paris, and intrigued by this theme, consider our new private tour in easy French on the influential feminist women of Saint-Germain-des-Près and the Latin Quarter*.

Alexander Kucharsky, Portrait of Olympes de Gouges (1748–1793). Image credit: Wikipedia (CC 4.0)

Olympe de Gouges (1748 – 1793)

One of the first female politicians: a key figure in the history of feminism

« Women have the right to mount the scaffold; they should likewise have the right to mount the rostrum »

« La femme a le droit de monter à l’échafaud; elle doit avoir également celui de monter à la tribune »

Considered one of the first feminists and one of the first women who entered political life, Olympe de Gouges was born Marie Gouze in 1748 in a bourgeois family that was not well-off. Married at age 17 against her will, she decided not to get married a second time after the death of her husband. She arrived in her 20s in pre-Revolutionary Paris and was received in the salons and cafés by the intellectuals of the period, and found her place among aristocrats, journalists and writers. Surprisingly, they welcomed the young woman who came from nowhere, and it was in their midst that she began to develop her own worldview. Influenced by the ideas of Les Lumières, Olympes de Gouges believed in total equality among all people, in a just distribution of capital and in assisting the needy.

She chose theater, which was at the forefront of avant-garde politics, to express her radical ideas. Performed by her own theater company, she became famous with her play The Slavery of the Blacks. In it she denounced the economics behind slavery and supported its abolition. After the theater company agreed to stage her play, she was asked to revise the text, which was considered too sensitive politically. “The arts have no gender,” she wrote in an attack on Comédie-Française.

Despite her disappointment with the world of theater, de Gouges was convinced she had a contribution to make to public discourse and edited a newsletter, Lettre au Peuple (Letter to the People), in which she developed a series of social reforms.

Women did not have the right to be elected to public office or to vote, but de Gouges started to publish pamphlets and to distribute brochures and petitions to the National Assembly. Her rhetoric challenged the society she lived in.

The pinnacle of her work was “The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen,” published in 1791 in which she stated: “A woman has the right to be guillotined; she should also have the right to debate.”

She campaigned for the right for women to divorce and obtained it in 1792. She campaigned in favor of a system of civil partnerships that would replace religious marriage.

If de Gouges’ views on gender equality were considered revolutionary, when it came to the revolution itself, she was relatively moderate. She often advocated a constitutional monarchy, like the system in present-day Britain. When the Reign of Terror began under Robespierre and hundreds of thousands of people were arrested and tens of thousands murdered, 17,000 were guillotined following fake trials. In a letter to Robespierre she wrote “Each hair on your head carries a crime”. She was among the first to grasp that Robespierre was a demagogue who talked about democracy but actually aimed at personal power and dictatorship. She was arrested and sentenced to death in 1793. As she walked up to the guillotine, she declared: “Children of the fatherland, you will avenge my death.”

George Sand by Nadar, 1864. Image credit: Wikipedia (public domain)

George Sand (1804 – 1876)

France’s most famous 19th century female writer

“The cigar is the essential complement to any idle and elegant life”**

« Le cigare est le complément indispensable de toute vie oisive et élégante »

George Sand, whose real name was Amandine Aurore Lucile Dupin, was born in Paris and brought up in the country home of her grandmother. She was only 19 when she married Casimir Dudevant, the son of a baron and a servant girl. She left him eight years after, leaving their two children behind as well. Although she wasn’t officially separated from her husband until 1835, after moving to Paris in 1831, she soon began to have many affairs.

In 1831 Sand started to write for Le Figaro, the famous daily newspaper. During this time she got to know several poets, artists, philosophers, and politicians, and wrote a novel with her lover Jules Sandeau, Rose et Blanche, under the masculine pseudonym Jules Sand. The reason why George Sand and other female writers of the 19th century published under a male pseudonym was because it allowed them to publish without prejudice in male-dominated circles.

Ivan Turgenev once said of Sand “what a brave man she was, and what a good woman”.

She was one of the 19th century France’s most prolific writers. Her first independent novel, Indiana, was published in 1832. While this novel is in no way autobiographical, it is clear that Sand drew inspiration from her own unhappy marriage. She received recognition for this novel almost immediately after it was published.

George Sand’s famous relationships

Sand conducted affairs of varying duration with Jules Sandeau and the French poet Alfred de Musset. One of her most famous affairs was with composer Frédéric Chopin and lasted 10 years. She officially separated from her husband in the midst of her bohemian life, which only added to her scandalous reputation. Later in life, she became close friends with Gustave Flaubert. She also engaged in an intimate friendship with actress Marie Dorval, which led to widespread but unconfirmed rumors of a lesbian affair.

Dressed like a man

George Sand lived as she pleased which was very rare for women at that time. In the early thirties she started to developed her unique lifestyle, dressing as a man without a permit. At that time social customs were very strict regarding women’s clothing and women were mainly wearing dresses, underskirts and painfully tight corsets. On November 7, 1800, the prefecture of police of Paris issued an order prohibiting women from wearing men’s clothing in public. The city order declared that “any woman who wishes to dress as a man, (toute femme désirant s’habiller en homme) must present herself to the prefecture for authorization.” Most of the female pants-wearers of the 19th century did so for practical reasons, but also at times to subvert dominant male stereotypes.

Sand was well known for smoking tobacco in public. She smoked cigars, for which she remained famous, but also cigarettes. Women, and particularly aristocrats, loved tobacco and smoking became fashionable in the 19th century. And, while the price of manufactured cigars increased, cigarettes changed in appearance with tobacco rolled up in a sheet of paper. The product became an attribute of dandies, and later that of women, and in particular “lionesses”, these first feminists of whom George Sand is the figurehead. It is perhaps to Sand that we owe the feminization of the cigaret, which, under her pen in 1830, became a “cigarette”.

** I have chosen this quote as the cigar was considered a male attribute.

Political views

Sand authored criticism and political texts. Because of her early life in the countryside brought up by a wet-nurse, she sided with the poor and working classes as well as women’s rights. When the 1848 Revolution started, she began to be an ardent Republican. Sand started her own newspaper, which was published in a workers’ publishing house.

She became politically very committed after 1841 and the leaders of the day often consulted with her and took her advice. She was a member of the provisional government of 1848, and during Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état of December 1851. Sand was known for her political commitment and writings during the Commune of Paris in 1870, where she took a position for the Versailles assembly against the Communards (members and supporters of the short-lived 1871 Paris Commune formed in the wake of the Franco-Prussian war) and France’s defeat.

George Sand changed Paris with her novels, her political views and her unique version of feminism. She has been considered a pioneer of feminist thought. She incorporated her philosophy of equality for women into her novels, plays, and essays.

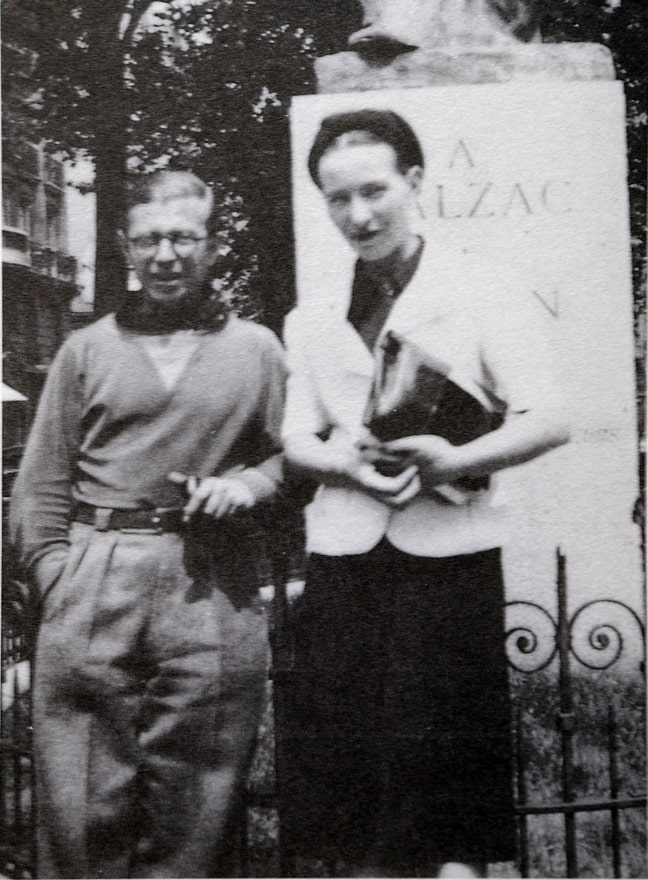

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir at the Balzac Memorial. Image credit: Wikipedia (public domain)

Simone de Beauvoir (1908 – 1986)

Second-Wave Feminism

“One is not born but rather becomes a woman”

« On ne nait pas femme, on le devient »

Where first-wave feminism was concerned with women’s suffrage and property rights, the second wave widened the scope with regards to sexuality, family, the workplace and reproductive rights. Was Simone de Beauvoir a feminist? Although she did not at first define herself as a feminist, her landmark book ‘The Second Sex’ was one of the most inspirational publications to the activists of the Women’s Liberation, the political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism that emerged in the late 1960s and continued into the 1980s in Western countries. However when 1960s feminists approached her, she was at first not very enthusiastic to join their cause.

The Second Sex 1949

In ‘The Second Sex’, published in 1949, Simone de Beauvoir downplayed her association with feminism as she then knew it. Like many of her associates, she believed that socialist development and class struggle were needed to solve society’s problems, not a women’s movement.

Beauvoir’s book outlines the ways in which women are perceived as “other” in a patriarchal society, second to man, who is considered and treated as the “first” or default sex. In the book, Beauvoir famously stated “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Women are different from men because of what they have been taught and socialized to do and be. In 1949, this was a truly radical idea.

According to Beauvoir it was dangerous to believe in an eternal feminine nature, in which women were more in contact with the earth. This perception was just another way for men to control women, by telling them they are better off in their cosmic, spiritual “eternal feminine” world, kept away from men’s knowledge and especially left out of the men’s concerns like work, careers, and power.

A return to enslavement

The notion of a “woman’s nature” struck Beauvoir as further oppression. She called motherhood a way of turning women into slaves. It was not meant to be slavery but it usually ended up this way in society precisely because women were told to concern themselves with their divine and feminine nature. They were forced to focus on motherhood and femininity instead of politics, technology or anything else outside of home and of family.

Women’s Liberation Movement

Like many of her associates, Beauvoir believed that socialist development and class struggle were essential to solve society’s issues, not a women’s movement. When during the sixties she was approached by feminists, she did not rush enthusiastically to join their cause.

The Women’s Liberation Movement helped Beauvoir to become more open the concept of day-to-day sexism women experienced. Yet she did not think it was beneficial for women to refuse to do anything the “man’s way” or refuse to take on qualities deemed masculine. Some radical feminists organizations rejected leadership hierarchy as a reflection of masculine authority and said no single person should be in charge. Some feminist artists declared they could never truly create unless they were completely separate from male-dominated art. Simone de Beauvoir acknowledged that Women’s Liberation had contributed to women’s emancipation, but she also believed that feminists should not utterly reject being a part of the man’s world, whether in organizational power or with their own creative work.

Simone Veil. Image credit: Wikipedia (CC0)

Simone Veil (1927 – 2017)

A Feminist Icon in France

“Men owe us what they imagine they will give us. We must forgive them this debt.”

« Les hommes nous doivent ce qu’ils s’imaginent qu’ils vont nous donner. Nous devons leur pardonner cette dette. »

In 1943, Simone Veil was a young Jewish girl living in France when the Vichy Government was collaborating with Nazi Germany. Aged only 16, she was arrested by German troops and taken to Auschwitz with her mother, her father and sister. When the camp was dismantled in 1945, they were incarcerated in Bergen Belsen. While Simone and her sister survived the Holocaust, Simone’s mother, brother and father did not. Still only 17, Simone returned soon after to France, devastated by the loss of her family members but determined to undertake a career in the law sector. She studied law at the University of Paris and the Institut d’études politiques, where she met Antoine Veil (1926-2013), a future company manager, whom she married.

She became a Magistrate in the French Ministry of Justice in 1956 and specialized in human rights, especially the rights of women and prisoners. In 1964, Simone became the Director of Civil Affairs where she guaranteed the right to dual parental control of family legal matters and adoptive rights for women.

A decade later, her appointment as health minister in the conservative administration of President Valéry Giscard D’Estaing paved the way to ease access to contraception.

The Veil law 1974 legalizes abortion

During the sixties, one million women in France had abortions every year. Condemned to secrecy, they did so in dangerous conditions for their health. The Manifesto of the 343 (Manifeste des 343) was a petition signed by 343 women including Catherine Deneuve, Françoise Sagan and Simone de Beauvoir who had the courage to say I have had an abortion. It was an act of civil disobedience since abortion was illegal in France at that time. By admitting publicly to having aborted, they exposed themselves to criminal prosecution. On April 5, 1971, the manifesto called for the legalization of abortion and free access to contraception and paved the way to legalize abortion. In 1973, Beauvoir pushed through laws to liberalize contraception in France.

On November 26, 1974, she gave a speech to the National Assembly which remained famous. The audience of the National Assembly was almost entirely composed of conservative men and Veil passionately defended a woman’s right to safe and legal abortion. She claimed that no woman resorts to an abortion with a light heart. “One only has to listen to them: it is always a tragedy.” Despite huge criticism from the right wing of French politics, a three-day debate and comments which compared abortion to Nazi euthanasia, the law eventually passed in November 1974 thanks to support from the left-wing opposition. Today, the Loi Veil enjoys overwhelming support in France, where few mainstream politicians dare to challenge it.

Simone Veil died at the age of 89 in 2017 and is the fifth women (along with 75 men) buried in Paris’s domed secular mausoleum, the Panthéon. The other women are Marie Curie, whose scientific breakthroughs changed the face of modern medicine; Sophie Berthelot, who was buried alongside her husband, the chemist and politician Marcellin Berthelot; Geneviève Antonioz de Gaulle, a heroine of the French resistance; and Germaine Tillon, a French ethnologist who helped prisoners flee and organized intelligence for the Allied forces between 1940 and 1942.

* If you learn French, French à La Carte organizes private tours in easy French to explore the city and practice your conversational French at the same time. Immersion in vibrant Paris neighborhoods, gourmet tours or our latest private tour on influential feminist women in Paris, these are examples of what we offer. Learning French in context is a fantastic way to embark upon a unique experience in Paris and practice your comprehension & speaking skills.

Image credit: Unsplash, Les Anderso

Lead photo credit : Simone Veil. Image credit: Flickr, ActuaLitté (CC BY 2.0)

More in feminism, French feminists

REPLY