The History of the Communards’ Wall in Père Lachaise Cemetery

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On the Avenue Circulaire on the outer pathway of Père-Lachaise Cemetery, a plain stone plaque is set into the wall with the inscription, ‘Aux Morts de la Commune, 21-28 Mai, 1871.’ (To the dead of the Commune.) Easy to miss, the simple inscription gives no indication of the horrors this wall witnessed in one of the most turbulent periods of French history.

The Association of the Friends of the Paris Commune hold a commemoration ceremony at the wall every year on the 28th and 29th of May, keen to stress that the elaborate, haunting sculpture of a goddess, fatally wounded, falling back with outstretched arms, also on the perimeter path of Père-Lachaise, is a monument to commemorate the whole period encompassing the short-lived Paris Commune, but not the infamous slaughter at The Communards’ Wall (mur des fédérés).

The government of the Paris Commune lasted 74 days. It was a movement formed in protest at France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war which resulted in the working classes feeling ostracized and ignored. When the Prussians besieged Paris in 1870 the poor were made even poorer still and were reduced to eating cats and rats to survive.

The seeds of the Franco-Prussian war were born in 1865 when Napoleon III, the ruler of France, agreed a deal with the Prussian prime minister Otto Von Bismarck that France would not involve herself between any wars between Prussia and Austria and specifically not ally herself with Austria nor allow Italy to claim Venetia. Later Napoleon III reneged on the deal, violating the original Bismarck agreement and signing a treaty with Austria about Venetia and allowing Austria to go to war with Prussia. It was to prove to be a costly mistake for France.

Prussia had annexed numerous territories already forming the N. German Confederation and began looking southwards to expand its influence.

The prospect of a Prussian King on the Spanish throne and the powerful country that would then be sitting on France’s borders provoked France to declare war on Prussia. The war lasted from July 19th, 1870 until May 10th, 1871 when France was defeated, resulting in the unification of Germany. (To add insult to injury on January 18th,1871, King William I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor at Versailles, the former palace of French Kings.)

Paris had already surrendered on January 28th against the wishes of many Parisians. France had already lost Alsace and much of Lorraine and were facing huge payments of five billion francs to Germany. An armistice was signed on February 26th and ratified on March 1st but dissatisfaction amongst the radicals in Paris, the newly formed Communards, encouraged them to step into the vacuum of the government being based away from Paris in Versailles, and they established their own government in Paris before the Treaty of Frankfurt was signed on May 10th.

The Communards’ aims were far reaching (and ironically later became incorporated into French law); they included the right for Paris to elect its own mayor, separation of church and state and most progressively, economic and social reforms including those by female communards.

Many of the wealthier Parisians left Paris, even though some agreed with the Communards’ cause, but the main Communard force remained in the poorer, working class areas of northeastern Paris like Montmartre, Belleville etc.

On the morning of March 18th, the government based in Versailles sent military forces into Paris to collect canons and machine guns. In the uprising that followed, the insurgents along with the National Guard, who had changed sides, controlled the city and declared the Paris Commune the new government. The ‘official’ government then prepared for battle.

The Communards were hopelessly outnumbered. The Versailles forces numbered around 130,000 men; the Communards who included women and children who actually defended the Commune numbered less than 20,000 but rough estimates of supporters of the Commune who were either killed in the fighting, gunned down indiscriminately afterwards or summarily executed ran as high as 25,000.

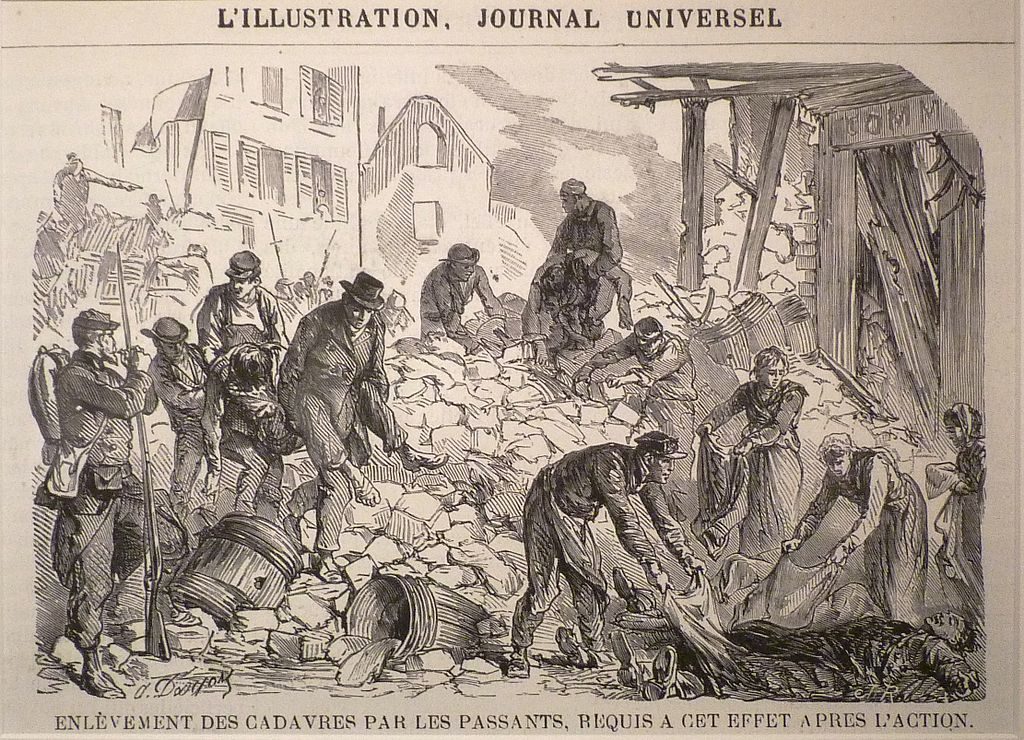

When the battle was over, Parisians buried the bodies of the Communards in temporary mass graves. They were quickly moved to the public cemeteries, where between 6,000 and 7,000 Communards were buried. Credit © Public Domain

The ‘trials’ held at Parc Monceau, Châtelet and the Luxembourg Gardens were complete travesties; often lasting just seconds, it was enough to simply be working class, a plebeian, for a guilty verdict. Bodies were covered in lime and thrown into the river, impossible to know a true figure.

The soldiers from Versailles were pitiless in their ferocity in fighting the Communards who fought from behind barricades right across the city. The government in Versailles wanted a lesson to be taught to other communes in cities across France and so operated with the Prussians to totally repress the insurgents. During the weeks of the Paris Commune, the Tuileries Palace and the Hotel de Ville were burned and the Vendôme column toppled. Fearful of the spread of the Paris Commune’s political and economic ideology to cities such as Lyon, Narbonne, Marseille and Bordeaux, the Paris Commune was to be obliterated.

And so it was that the last 147 members of the Commune were cornered in Père-Lachaise cemetery, still resisting in the mud under the wall with their bare hands.

All 147 were lined up against the wall and executed on the 28th of May, 1871. This was the end of the week forever known as La Semaine Sanglante, The Week of Bloodshed.

The uprising was crushed but never forgotten.

The Paris Commune has been held up as an example by both Marx and the Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong. Marx stated that it was a living example of a “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

It was certainly an example of extreme bravery against all odds in the fight for truly democratic society.

Lead photo credit : Credit © Flickr, Alex Shly

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY