Manifestations and Revolutions: Remembering May 1968

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Graffito in University of Lyon classroom during student revolt of 1968 / Public Domain

France has never done manifestations and revolutions half heartedly. Indeed they may well be built into the French psyche, protests a natural response to discontent, but nowhere was the call, ‘To the Barricades!’ demonstrated as enthusiastically as in the Revolution of May 1968.

I had been in Paris 6 months, an au pair in the 15th Arrondisement, (although spending all my spare time in St Germain and the Latin Quarter), when the first faint rumblings of trouble brewing began to be heard from the University of Nanterre. After months of conflict with the authorities, the administrators shut down the University on the second of May. The next day students met at the Sorbonne to protest against the closure and threatened expulsion of students. A protest march was organized by the Union Nationale des Etudiants on May 6th against the police invasion of the University.

No one could have envisaged the consequences that shook France and French society for the three, often bloody, weeks that followed.

Public square of the Sorbonne, in the Latin Quarter of Paris / Public Domain

As the 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched towards the Sorbonne, the baton-wielding police charged. Some protestors began throwing paving stones, others built barricades; the police responded with more force and tear gas arresting hundreds of students.

Despite an attempt at negotiations demanding that the police leave the Universities and drop all charges against the students, the police remained, occupying the Universities. From there on the manifestations escalated rapidly.

Up until Friday May 10th, the protests were mainly considered to be a student uprising, not particularly affecting everyday life in Paris. Of course in St Germain and the Latin Quarter especially, the edginess in the streets was palpable-still for those like me uninvolved in French student’s politics, except as a spectator, it was all a bit of a lark really. I had never seen cobbles ripped from streets or barricades manned by people my own age and it was inescapably exciting.

Madame Lobjois, my employer, was a teacher, so as she explained to me the basics of the student’s objections. I told her of the reality of being tear gassed in St Germain. Coming up the steps of the metro one day, the acrid, burning smell of tear gas came down to meet us. The choice was either to turn back against the crowd and go deeper into the station or make a run for it through the line of CRS outside on the street. The CRS en masse were a frightening vision, heavily armed and dressed all in black wearing shiny helmets and long leather boots, their menacing appearance matching their reputation of often using indiscriminate and excessive force. I never knew why we were being tear gassed that day in the metro, but decided instinctively to make a run for it- rather be hit by a baton then trapped underground. We had scattered into the daylight, eyes streaming, coughing uncontrollably, dodging as best we could the batons of the CRS. I was lucky, many weren’t. If you were lucky, it was an adventure, if you weren’t you had a very sore head at the very least. It still seemed though that events on the Rive Gauche and life in Rue Brancion a short metro ride away where I lived, were worlds apart.

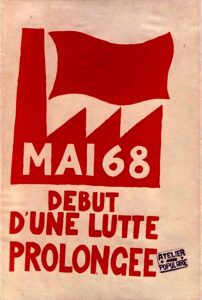

Revolutionary poster, France, May 1968 / Public Domain

This all changed on May 10th when a huge crowd congregated on the Left Bank and the security forces blocked them from crossing the river. The protestors erected more barricades and the police attacked once more. The confrontation lasted all night. Cars were burnt and Molotov cocktails thrown. The heavy handed, often brutal retaliations by the security forces resulted in support for the students coming from diverse quarters; poets, singers and left wing unions threw their collective hats into the ring and called for a one day strike and demonstration on Monday May 13th.

Over a million people marched through Paris that day but despite Georges Pompidou promising to release all prisoners and reopen the Sorbonne, the students, inspired by the communist Daniel Cohn-Bendit, occupied the Sorbonne declaring it autonomous and the “people’s university”. At this point, some support for the student’s cause fell away but the momentum for an uprising amongst ordinary workers was snowballing to an unstoppable degree into an anti government, anti French society movement that would affect not only the citizens of Paris but the whole of France.

Strikers in Southern France with a sign reading “Factory Occupied by the Workers.” Behind them is a list of demands, June 1968 / Public Domain

Workers began occupying factories including the Renault factories in Rouen and Boulogne-Billancourt. By May 16th, 200,000 workers were on strike. A week later 10,000,000 workers joined the strike, approximately two thirds of the French work force. This was not all union-led; many work forces decided to strike quite independently of union influence.

(To put work force grievances into a little context, 25% of French workers in 1968 were earning less than 500 francs a month. As an au pair with room and board (and not too much work…) I was earning 400 francs a month and my social security was paid by the family.)

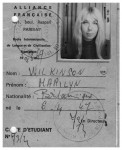

Undeterred by the tear gas episode, Molly and I continued our evenings in St Germain where we were ignominiously arrested in Rue Dauphine in the early hours one morning by plain clothes policeman. (See my article “Remembering Le Tabou-33 Rue Dauphine May 1968.”) There was no police brutality-we hadn’t been suspected of being communist insurgents, simply not having our identity papers with us. Our arrest was done with good humored amusement, our stay in the police station relatively brief, and we put it down as another adventure, not to have been missed.

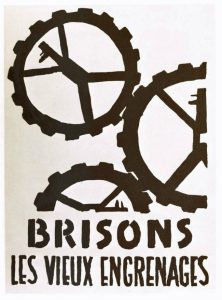

From the catalogue of an exhibition on French May 1968 protest posters: Les Affiches de mai 68 ou l’Imagination graphique / Public Domain

Light hearted as our escapades had been, in contrast the mood in France hardened.

By May 18th, coal production had stopped and public transport had halted in Paris. Petrol supplies had dried up by May 20th, and withdrawals from banks limited to 500 francs. Rubbish was building up in the streets and I was sent to the local Mairie to collect the designated, heavy duty rubbish bags. Cross channel ferries stopped operating and Air Traffic Controllers and the French TV station ORTF joined the strikes, leaving the population huddled around radios waiting for De Gaulle to speak.

Without the metro and taxis impossible to find and going stir crazy, I decided that walking to St Germain was not such a terrible idea. From Convention it was a straight walk the length of Rue de Vaugirard. Getting there was uneventful, walking home at 4 am, not such a brilliant plan. Strike pickets huddled around braziers and probably bored rigid found the sight of a lone mini-skirted female irresistible and promptly took chase. Short skirt or not, I was still the faster sprinter and left them behind but it was a lesson well learnt and I no longer roamed the streets in the early hours.

When the funeral directors went on strike there was a running joke about it not being a good time to die in Paris.

Monday May 27th found the government guaranteeing an increase of 35% in the industrial minimum wage and an all round 10% increase in salaries. But such was the state of anarchy that De Gaulle and his entourage fearing a complete breakdown in the authorities, flew to the military airfield at Saint-Dizier to seek reassurance from his Generals of the armies support to help maintain his grip on power.

“Vive De Gaulle” is one of the graffiti on this Law School building. / Public Domain

Finally on May 30th, De Gaulle appeared on French TV (although we were still huddled around the radio!), promising new elections. A large crowd of vociferous De Gaulle supporters marched down the Champs-Élysées, cars sounding their horns in a cacophony of noise and effectively it was all over.

By June 5th, most strikes were over and the status quo more or less restored.

There are endless theories that with more organization and coordination the government could have been toppled but it was not to be. My own simple view point was that the French, whilst loving the thought of a revolution, prefer it not to go on too long and the reality of a breakdown in all services was best curtailed to a short (but thrilling) period of time.

I was just thankful that the metro was running and I never again would have to run from a strike picket in unsuitable shoes…

Lead photo credit : Revolutionary poster, France, May 1968 / Public Domain

More in history in Paris, history of France, Paris 1968, Paris history, Paris manifestations, Paris may 1968, Paris revolutions, protest, student protests, uprising

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY