33 Rue Dauphine: Remembering Le Tabou in May 1968

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In January 1968, within a month of arriving in Paris and with all the acute olfactory senses of a pig finding truffles, Molly (my new friend) and I unearthed Le Tabou, a cellar club in Rue Dauphine. Pablo, the DJ, downstairs in the smoke filled cellar, played R&B and soul music- Otis Redding, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, James Brown-anything that was good, exciting and loud. Le Tabou became our second home, we frequented it two or three times a week, stumbling out at four in the morning to find a brightly lit café for a much needed café au lait before taking the first metro home.

Le Tabou opened in 1947, following in the footsteps of the Club des Lorientais. Originally it was a late-night drinking haunt for press distribution workers as it had an alcohol license until 4am. It was soon taken over by the intellectuals, musicians and poets of St Germain and Montparnasse, after the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots had closed their doors for the night. Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Boris Vian and Jean Cocteau were regular customers. Juliette Greco sang there and Miles Davis played on the tiny stage. (They had a passionate affair, Paris was a refuge for black jazz musicians in the post war era; Greco was horrified when later she met up with Davis in America to find that as a black man he was not allowed to drink in the same bar.)

As the popularity of Le Tabou took off, it was not uncommon for neighbours fed up with the noise of customers leaving in the early hours, to empty their chamber pots on to their heads. Fortunately for us, this unsavoury habit had stopped.

The entrance door to Le Tabou opened directly off Rue Dauphine. Upstairs there was a cloakroom, toilets and a small bar. Down a steep flight of stairs was the vaulted cellar club. There was a tiny stage at the far end, a dance floor and a bar at the other end. Pablo sat surrounded by his records at the back of the room. There was no air conditioning or extract fans– just pure unadulterated cigarette smoke. About 2 in the morning we’d have a break (and breathe in fresh cigarette smoke) in the Bar Nesle, just across the road. Strangely when I got up the courage this year to revisit Le Conti, the Nesle and Le Relais Odeon on Blvd St Germain, they all seemed smaller than I’d remembered, as if I’d only been a small child there instead of a 20-year old.

The bar man downstairs in Le Tabou was so archetypically French, dark, handsome and not tall, that Molly and I fell in love with him on sight. We would watch him polishing the glasses behind the bar to an impressive, smudge free shine and we afforded him all the attention and admiration due a surgeon performing open heart surgery with a tin opener. His conversation consisted of “Vous êtes belles” and “Voulez-vous coucher avec moi?” Not a word about the weather or the state of our health. After two weeks Molly and I gave ourselves a metaphorical slap on the hand and promptly and individually fell out of love with him.

Sadly Le Tabou closed its doors in the late 90s and the building is now a very swanky hotel, L’Hotel d’Aubusson. I couldn’t bear to enter it even for a coffee. My memories of Le Tabou and Rue Dauphine are still so vivid that each time I go to Paris I rent a studio closer and closer to Rue Dauphine– the last one on the corner of Rue de Buci– just so I can walk the same streets I walked on 45 years previously. From the 5th floor of my tiny studio I can see the packed tables on the terrace of Le Buci café. At weekends, the last stragglers leave at 4am. I am sadly not one of them and am out of bed not because I’ve been out clubbing but due to insomnia.

Before Le Tabou, Molly and I usually went to Le Conti for a pre club drink (or two). Le Conti, on the opposite corner of Rue de Buci was managed by a very small but formidable French woman. Arms folded severely under her impressive chest, she, and her equally tiny but just as formidable dog, guarded the till with all the charms of Attila the Hun. Clientele were ejected on a whim. If she didn’t like your face, you were out. Obscurely, she approved of Molly and me, so most evenings we enjoyed La Madame and her chien in a free and often volatile, cabaret. If Madame REALLY didn’t like someone, her sleeves rolled up all by themselves and with gimlet eyes and in very unladylike terms she would evict the poor unfortunate into the cold night air.

Our chosen bars were not just picked randomly or for their proximity to Le Tabou but also for their toilet facilities. Footsteps were out as were toilets on platforms, (you could so easily fall off taking a bow.) Toilets on platforms were surprisingly common, I guess to belatedly run the plumbing underneath, but could reduce us to near hysteria, Molly often making an abdication speech through the toilet door. It was surprising how so many lovely bars and cafes had to be discounted because of the grimness, downstairs in the gloom, of their toilettes.

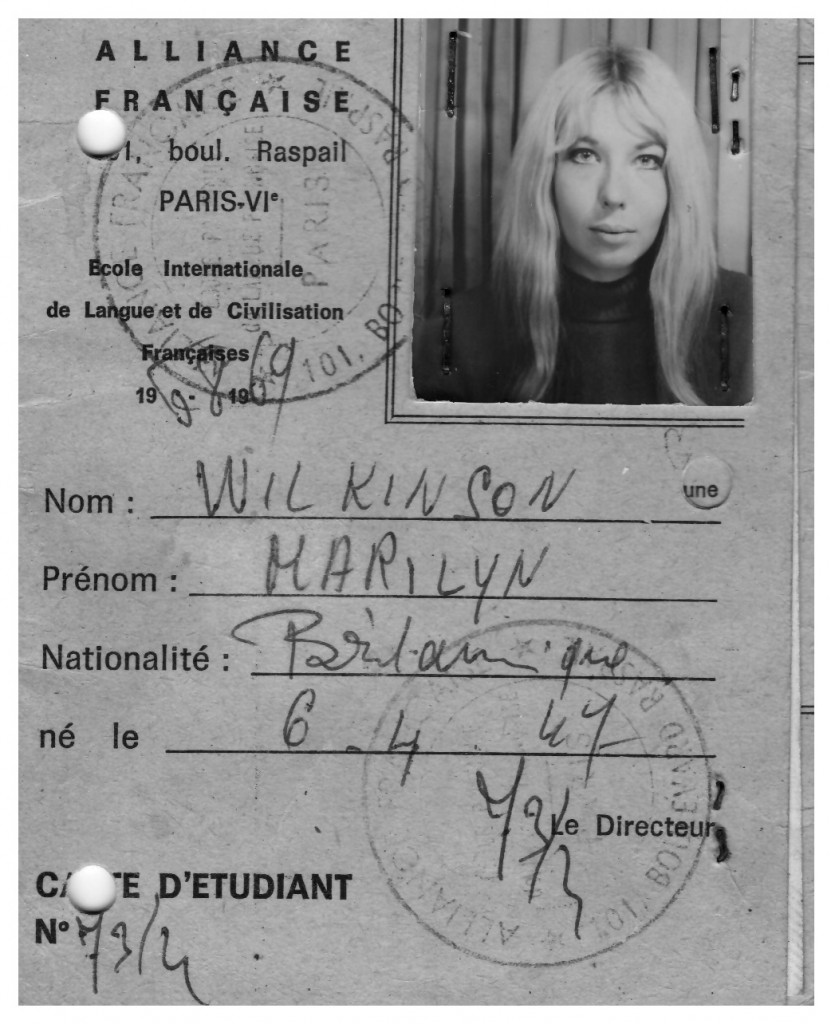

During the manifestations of May 1968, Molly and I were wending (probably a trifle unsteadily) our way across the road from Le Conti heading for Le Tabou when we were stopped by two plain clothes policemen asking for our identity papers. We were aware of course that the French had to have their papers on them at all times but we were BRITISH and what was more, our passports were a precious commodity, too easily lost in a bar or cloakroom in St Germain to ever take them out with us.

“Sorry,” we’d smiled winningly. “We’ve left them at home”. Clearly our idea of a winning smile did not concur with the ideal of French plain-clothed policemen and they’d nodded understandingly before cheerfully bundling us both into the back of a very handy panier à salade parked opposite. (This was a police van with metal grids on the windows.) We were not alone, but surrounded by various ‘ladies of the night’, who in truth were sporting longer skirts than us and until they heard we were English, probably thought we had invaded their patch. After a two-hour stint in the nearest police station, where it was obvious we were just being taught a lesson, we were released to make our belated way to Le Tabou for the last hour of dancing. Le Conti was closed by then but Madame, who had witnessed everything, gave us drinks on the house the next time we went to make up for the indignity of sitting in the back of a panier à salade in the middle of Rue Dauphine like common criminals.

Madame is obviously long gone and convinced that Le Conti had shrunk, I asked the barman two months ago when had it changed? He gave a Gallic shrug and said he’d no idea and when was the last time I’d been in there? I realised my mistake immediately. “45 years ago,” I’d admitted with great reluctance. We both regarded each other with something akin to horror. He probably worried I’d fall off his bar stool and crumble into little pieces, and me painfully aware that he probably wasn’t even born 45 years ago.

He doesn’t know what he missed.

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY