Teacher, Laundress, Seamstress: Women of the Paris Commune

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Outside a school in the 20th arrondissement the wall is covered with 19th-century photographs of women. The photos are faded, the women unsmiling. What they share is their participation in the Commune. This worker-led government controlled Paris in the spring of 1871 in the aftermath of the disastrous Franco-Prussian War. After two months, the Commune was brutally suppressed by the French government, culminating in the Semaine Sanglante or Bloody Week. The Mur des Fédérés at the back of Père-Lachaise cemetery marks the spot where 147 Communards where shot, marking the end of this experiment in working class local government.

Although men figure prominently in histories of the insurgence, the role played by women was key to the Commune’s shortlived success. They provided food and drink to the men and set up soup kitchens in local neighborhoods, and they also built barricades and took up arms to defend Paris when the troops arrived.

Cementery Père Lachaise (C) Peter Poradisch, CC BY 2.5

The women came from all walks of life but are rarely mentioned in histories of the uprising. By far the best known is Louise Michel. Louise’s beginnings were typically humble: born illegitimate in 1830, she was raised by her grandparents. Yet, unusually, Louise received an education and became a teacher.

She opened a school in Paris, became acquainted with Victor Hugo and promoted the rights of women. She served as an ambulance worker during the Siege of Paris (when the Prussians encircled the city for four months) but really revealed herself as a militant anarchist and feminist during the Commune. She was president of the Comité de Vigilance des Citoyennes in Montmartre where she organized local women to run a soup kitchen for starving children. At the same time, she offered to assassinate the President of the Republic, Adolphe Thiers, who was reviled for his opposition to the Commune. Perhaps fortunately for history, Louise’s offer was refused even by the anarchists and the fledgling Third Republic survived its first potential leadership crisis.

Louise was deported to New Caledonia. She was allowed to return to France in 1880 – a move which the government may have regretted as Louise’s radicalism had only intensified during her Pacific exile. She continued to write and militate for anarchist and feminist causes and was under constant police surveillance for the rest of her life. At the age of 60 she was imprisoned for taking part in insurrections.

If Louise Michel has become the public face of women of the Commune, behind her is a small army of teachers, seamstresses, laundresses, shopworkers and domestic servants who took up the cause, and arms, to protect Paris from government control. Most have remained anonymous but the stories of a handful have survived, often because of their reputation as petroleuses and the high-profile trial that followed their arrests.

Louise Michel (C) J.M. Lopez, Public Domain

The petroleuses were a group of women who were put on trial for allegedly starting the fires that destroyed large areas of Paris during Bloody Week. Several major buildings were totally destroyed, including the Hôtel de Ville and the Tuileries Palace, not to mention numerous smaller conflagrations across the city.

The petroleuses denied setting the fires but the government wanted vengeance and they were mostly deported. The photographs on that school wall include their official police portraits. The women are unfashionably dressed, showing in their faces the hard lives they had suffered. But their biographies are fascinating because they show these women living lives outside the middle class ideals of marriage, family, and home.

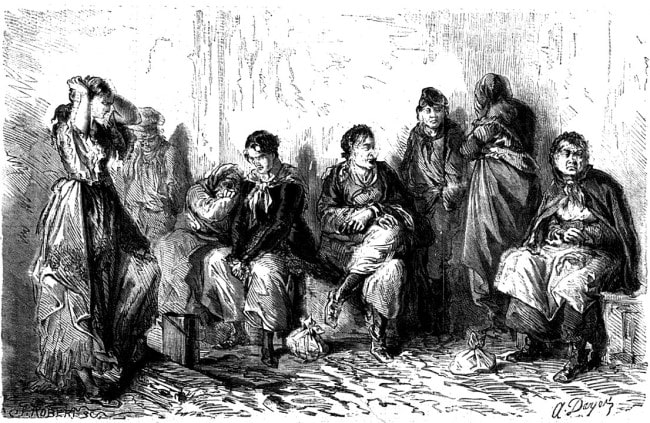

Pétroleuses arrested in Versailles. (C) Robertson, Public Domain

Take Léontine Suétens, for example. A laundress by trade, when the Commune began she had already been in prison and had lived, unmarried, for six years with a man called Aubert Louis. When Louis joined the barricades, Léontine accompanied him to provide meals for the men, and took part in the battles on Paris’s western outskirts. Later, she helped build barricades in the 7th arrondissement and was accused of making petrol bombs (which she denied).

Portrait of Léontine Eugénie Suétens (C) (CC0 1.0)

Or Eulalie Papavoine, a seamstress, who fought alongside Léontine in the 7th arrondissement. Not only did Eulalie live with a man, Rémy Balthazar, outside marriage, but they also had a child together. At her trial she was accused of sharing stolen goods with Léontine and building barricades. Eulalie’s crime, in her own words, was simply to have organized ambulances for the injured men. Like Léontine, Eulalie was deported but was allowed to marry Balthazar to legitimize their son.

Photograph of Eulalie Lapavoine (C) (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Élisabeth Rétiffe was another woman “living in sin” who provided ambulance services to wounded féderés. She was seen on the barricades wearing a white blouse, red scarf and a rifle slung over her body. Despite her denials, she was sentenced to death, later commuted to forced labour in Guyana.

Not all the frontline combattants were uneducated working class women. Élisabeth Dmitrieff, despite being born illegitimate, received a good education in Russia and spoke several languages. After marrying, she and her husband moved to London where they knew Karl Marx.

During the Commune, she co-founded the Women’s Union for the defence of Paris and brought women together to form a trades union for female workers. She also stood on the barricades, in the Faubourg Saint Antoine, for which she was deported to a fortified prison. In 1879 she was pardoned on the understanding that she live in exile, which she did in Switzerland and later Russia, until her death.

Elisabeth Dmitrieff (C) Alphonse Liébert, Public Domain

Some influential Communardes were lucky to escape arrest. André Léo (real name Léodile Champseix) was born into a bourgeois family and well-educated. She was happily married, had twin children and wrote romantic novels under her pen name. So far, so conventional. But when her husband died in 1863, André launched herself into politics and feminism. When the Commune arrived, André was right in the middle of it. She belonged to the Women’s Union for the defense of Paris, worked on a commission to examine girls’ education and, alongside Louise Michel, worked on the Comité de Vigilance des Citoyennes de Montmartre. When government forces entered Paris, she fled to Switzerland, where she continued to mix with anarchists and write for radical journals. Her more intellectual involvement with the Commune distanced her from the petroleuses and perhaps for that reason she was lucky to avoid punishment.

There is no permanent memorial to the women of the Commune. Louise Michel has a Métro station, a public library and a square named after her, but the rest have disappeared apart from an occasional mention in histories of the Commune. But these neglected women played a vital role in an uprising that, 150 years later, still evokes strong feelings among Parisians.

Lead photo credit : Barricade 18 March 1871 (C) Unknown, Public Domain

More in Communards, France, history, Woman

REPLY