The Lost Palace of the Tuileries

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

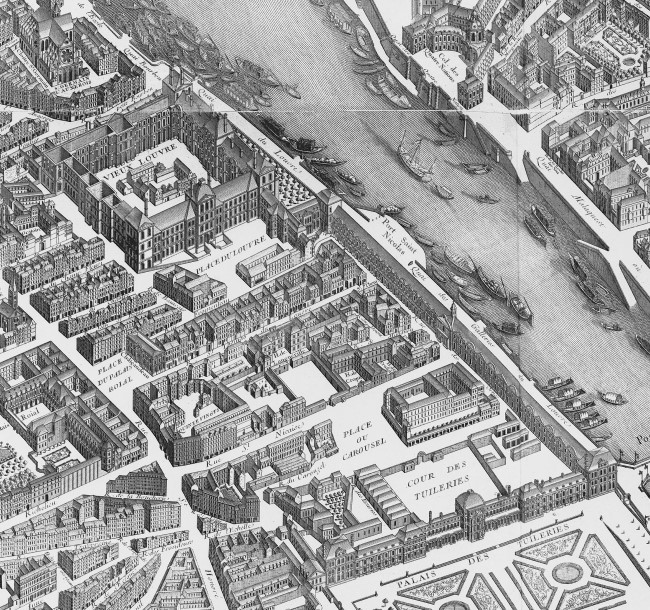

Imagine Paris in the 3rd century B.C. as a fortified village originally located on the Île de la Cité, between the left and right banks of the Seine River. The village, inhabited by the Celtic tribe known as the Parisii, was conquered by the Romans in A.D. 52. Roman Paris, then known as Lutetia, was not a particularly important village. It had a population of less than 10,000 and existed primarily on the left bank, rive gauche. The right bank, rive droite, was almost uninhabitable due to the vast marshes which extended from the present-day Place de la Bastille to the Marais.

During the Middle Ages, Paris grew rapidly and became one of the largest cities in Europe under the vision of King Philippe-Auguste (1180-1223). The right bank marshes were drained, main thoroughfares were paved, the central market of Les Halles was constructed, the building of Notre Dame de Paris continued, and the Louvre Fortress was built. A new wall was erected around the city of Paris, enclosing 253 hectares on both sides of the Seine. This new wall was 2.5 meters thick in some places, protected by wide, deep ditches, and fortified with as many as 500 towers. Several elements of the wall’s structure were later incorporated into the subsequent wall of King Charles V (1338-1380).

The Louvre Fortress, however, was not a royal residence. Instead, the Palais de la Cité was home to the Kings of France from the sixth until the 14th century. The site is now occupied by the Palais du Justice. Only a few vestiges of the vanished grandeur remain: the medieval lower hall of the Conciergerie (four towers along the Seine) and Sainte-Chapelle, the former chapel of the Palais. Between 1364 and 1380, Charles V undertook work on the Louvre Fortress, transforming it into a chateau. The old fortress became a comfortable residence consisting of apartments. A king’s library was set up, and this collection would, over the centuries, become the National Library of France.

During the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), when Paris was often under siege and held by the British, a dazzling variety of chateaux were transformed in the Loire Valley: Chambord, Amboise, Chenonceau, Fontainebleau, Chaumont, Tours, and Blois. Originally designed for defensive purposes, they were later renovated into the Italian Renaissance-inspired, revolving-door homes of the Royals, epitomized in the courts of King François I (1494-1547), and his son Henri II (1519-1559).

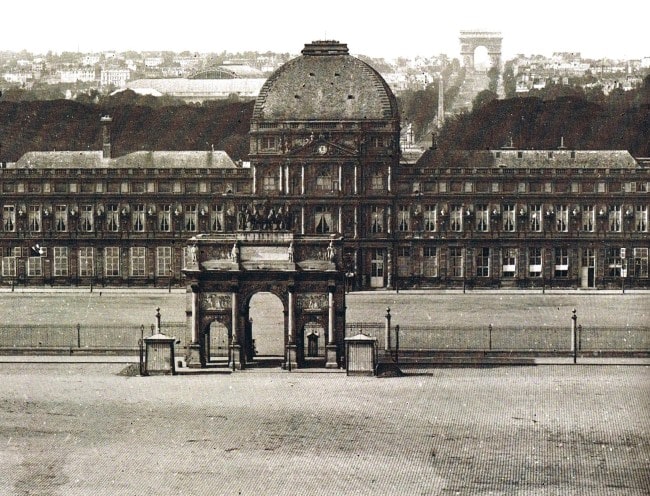

Tuileries Palace. (C) Unknown author. Public Domain

In 1533 Henri II was married Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) when they were both 14 years old. Catherine was the daughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici, and Madeleine de La Tour d’Auvergne. Within a month of her birth, illness killed both of her parents. Thereafter, she shunted between relatives and convents in Florence and Rome. Her uncle Pope Clement II eventually made a deal with François I for Catherine to marry his son Henri. When he inherited the French crown from his father, Catherine became Queen.

Catherine had 10 children with Henri. In 1559, during a jousting match before their daughter Elizabeth’s wedding to Phillip II of Spain, Henri took to the saddle against a young nobleman.

The Tuileries Palace in the 1600s. (C) Stefano della Bella/ Public Domain

He was hit with a lance that pierced his eye and brain. He died 10 days later at the Tournelles Palace, another royal residence, located north of the current Place de Vosges, where they were currently residing. Now a widow, she abandoned the Tournelles and moved with their son, François II, now king, and the royal family to the Louvre Palace.

Once Catherine took her place as Queen Mother, the idea of building an architectural masterpiece grew in her mind. Catherine envisioned a vast Italianate palace surrounded by extraordinary gardens laid out in the Florentine style with symmetrical squares of large alleys, flower beds, hedges cut into a labyrinth, and a grotto. She was a Medici after all, and was driven to leave a prestigious achievement to solidify the importance of her dynastic lines after her death. In 1563 she began to look for property outside Charles V’s walls. She found the rural area, in what would become the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the only area that met her needs: it was close to the Louvre, and few people lived there so she could expropriate the rural land at low prices. For Catherine, it was an excellent business decision. The only large buildings of the Faubourg Saint-Honoré were were three tile factories (tuileries) in operation since 1373. The factories were razed, but she kept their name.

Le Nôtre’s central axis of the Tuileries’ parterres in a late 17th-century engraving (C) Public Domain

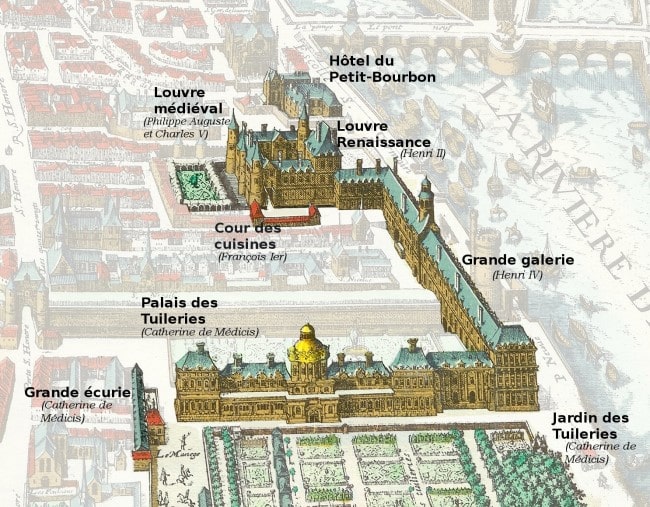

The original plan drawn up by the architect Philibert de l’Orme (1514-1570) was never completed. Had it had been realized, the palace would have covered an area 10 times larger than the Louvre Palace and grounds.The first stone was laid in May 1564. De l’Orme built the ground floor of the central pavilion and the two low wings that frame it, as well as an elegant staircase suspended over a vault, considered a masterpiece. After De l’Orme’s untimely death, Jean Bullant (1515-1578) became his successor. He created large pavilions, Marsan and Flore, at the southern and northern ends of the site.

Under the subsequent reigns of Catherine’s three sons, Francois II, Charles IX and Henri III, France sank into the Wars of Religion (1562-1598). The construction of the Tuileries Palace was abandoned. Superstitious since childhood, Catherine lived in an age when beliefs linked to magic and the black arts were common. Legend has it that her astrologer once predicted she would die near Saint-Germain, and since her original plan for a palace was located close to Saint-Germain de l’Auxerrois, she had another residence built on the site of the Bourse du Commerce, the Hôtel de Soissons. Of this grand building, only the famous Medici column remains. (This column can be seen outside the newly opened Bourse de Commerce, the museum housing the Pinault Collection.)

The old medieval Louvre (background) and the Tuileries (foreground) linked by the Grande Galerie along the River Seine, in 1615 (C) created by XIII/ CC BY-SA 3.0

King Henri IV’s marriage to Catherine de Medici’s daughter Marguerite (1572) was proposed as a token of peace between Catholics and Protestants, but the Wars of Religion did not end until 16 years later. Henri IV (1553-1610) lived at the Louvre Palace when in Paris. He was responsible for initiating the “Grand Design”, a project joining the Louvre and Tuileries Palaces via a 450-meter gallery parallel to the Seine. Henri IV particularly liked the Tuileries Garden, but made many changes, including planting 15,000 white mulberry trees for the production of silkworms. Rarely idle, he oversaw the building of the Pont Neuf and the Place Royale. Henri IV was assassinated in 1610. He was the father of Louis XIII and the grandfather of Louis XIV.

Portrait of Henry IV (C) Public Domain

The first person to actually reside at the Tuileries Palace was Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans in 1627. She was known as the Grande Mademoiselle, first cousin and lover of the Sun King, Louis XIV. At the King’s request the architect Louis Le Vau (1612-1670) reinvented the Tuileries Palace once again. Among the many transformations, he razed the pre-existing buildings and destroyed Philippe de l’Orme’s magnificent staircase. He and his assistant François d’Orbay also renovated the interiors and added a rectangular dome on top of the central pavilion.

They created a colonnaded vestibule on the ground floor and the Salle des Cents Suisses (Hall of the Hundred Swiss Guards) on the floor above, as well as a new grand staircase, installed in the entrance of the north wing. The king’s luxurious suite of rooms were on the ground floor, facing toward the Louvre Palace, and the queen’s on the floor above, overlooking the immense garden redesigned by Louis XIV’s landscape gardener Andre Le Nôtre. Louis XIV lived there until 1641.

Portrait of Anne Marie Louise d’Orléans (C) Attributed to Gilbert de Sève. Public Domain

When Louis XIV moved from the Tuileries Palace to Versailles, it was divided into official accommodations for retired artists and people with honorary responsibilities. By the middle of the 18th century, on the eve of the French Revolution, it was in a state of disrepair. In 1789, the storming of the Bastille took place. The Revolutionaries forced King Louis XVI, Queen Marie-Antoinette, and their children to leave Versailles and move back to the Tuileries Palace where they remained under guard. Less than two years later, in 1791, the royal family tried to leave France. They were captured in Varennes-en-Argonne, Lorraine, and brought back to the palace which, once their home, became their jail. The royal family escaped again, fleeing through the Tuileries Gardens, but were apprehended again. Unwilling to cede his royal power to the Revolutionary government, Louis XVI was found guilty of treason condemned to death in 1793. He was guillotined on what is now the Place de la Concorde. Nine months later, Marie Antoinette was also convicted of treason, and followed her husband to the guillotine.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) made the Tuileries Palace the centre of his imperial power. In 1808, as Emperor, he ordered the construction of the northern gallery. His nephew Napoleon III (1852-1870) also made the Tuileries the official seat of the Second Empire, lavishly refurbishing and redecorating the interiors. In the northern wing of the palace, the chapel, Galerie de la Paix, and the Salle de Spectacle were added. The southernmost pavilion, the Pavillon de Flore, served as the backstairs to the palace. Service corridors led to it. One could get from there to the sprawling basement, lit with innumerable gas lamps, where a railway had been laid down to bring food from the distant kitchens under the Rue de Rivoli.

The storming of the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792 and the massacre of the Swiss Guard. (C) Jean Duplessis-Bertaux/ Public Domain

In the aftermath of the French defeat against Prussia, the insurrection of the Paris Commune raged against Napoléon III’s government. In May 1871 the Tuileries Palace was captured and opened to the public. On May 20, a fire broke out inside the palace, skillfully set with kerosene, turpentine, tar, and explosives. It was orchestrated by the members of the Commune, the Communards. The palace burned for three days. Fortunately, all of the furnishings and artwork had previously been removed for safekeeping during the Franco-Prussian War. Today, the furniture and paintings remain in storehouses and are not on public display due to the lack of space in the Louvre Museum.

The ghostly shell of the Tuileries Palace stood undisturbed for the next 11 years. The remains of the palace were finally bought at auction by the entrepreneur Achille Picard for 33,500 francs. He, in turn, sold them. In 1883 the last vestiges of the Tuileries Palace were razed.

View of the Tuileries Palace after the 1871 fire and before the demolition of 1883. (C) Unknown author/ Public Domain

The management of Le Figaro newspaper bought pieces of marble which were cut into paperweights, and offered to subscribers. The Duke Jérôme Pozzo di Borgo and his son, Count Charles, also bought marble stones and had them transported by rail to Marseille, then transported by boat to Alata, Corsica. There, the duke had one of the Renaissance pavilions of the Tuileries Palace rebuilt into the Château de la Punta. Various other architectural pieces and sculptures were purchased and can be found in far-flung locations around the world — from Berlin, Germany to Quito, Ecuador.

The remains bought by the French State were scattered among the city and can be located at the Cour Marly du Louvre, the hall under the Carrousel du Louvre, the Jardin des Tuileries, bordering the terrace along the Seine, the courtyard of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the Trocadero gardens, Square Georges Cain, and in the Courtyard of the Special School of Architecture, among many others which are available online. Only the Pavillon de Flore and the Pavillon de Marsan have been preserved. They are located at the western ends of the Louvre Museum. The Pavillon de Marsan today houses the Museum of Decorative Arts.

The Tuileries Garden looking towards the Louvre. Photo credit: dronepicr/ CC BY 2.0

Will the Palais des Tuileries ever be rebuilt? The idea has surfaced from time to time, but is very unlikely. Another monument damaged by great fire, that of Notre-Dame de Paris in 2019, takes precedence. May 23, 2021 marks the 150th anniversary of the palace’s destruction.

Lead photo credit : The Tuileries Palace and the Louvre on the 1739 Turgot map of Paris, during the reign of Louis XV (C) Public Domain

More in history in Paris, marie antoinette, Napoleon, Royal

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY