Riots! Floods! Gangsters! Art Heists! Louis Lépine Dealt With Them All

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Louis Lépine was a legendary figure from the Belle Époque whose name was inextricably tied with the city of Paris. Lépine was Prefect of Police for the city, although his popularity at the time was debatable. He quelled major riots, stopped an infamous group of anarchist gangsters, and investigated the theft of the Mona Lisa. He was responsible the modernization of the Paris police force and created an influential exhibition of inventions that still operates to this day.

Born in Lyon in 1843, Louis Lépine was a student of law in his hometown and continued his studies in Paris and the German city of Heidelberg. He was awarded the Médaille Militaire for his bravery in in the Franco-Prussian War. After the conflict he became a lawyer and public administrator posted to various locations around France.

Louis Lépine became Prefect of Police for the Seine region in 1893 during a volatile period in Paris’s history. The position was akin to that of a chief of police & emergency services with a degree of political influence as well. Lépine’s reputation for maintaining public order ensured he held this position for many years.

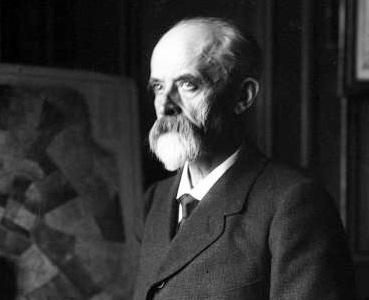

Louis Lépine shortly before his retirement. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Riots of the Bal des Quat’z’arts

Lépine was originally brought on board in July of 1893 to take control of a serious student uprising. His predecessor had lost control of the situation. The Latin Quarter became the focus of four days of rioting, resulting from the deshabille of students at the annual ball of L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts. While showing their bohemian side, students attending the Bal des Quat’z’arts also showed too much skin, with many partygoers ending up naked in the streets. Artist-model Sarah Brown was the pivotal figure of an uprising that raged for days and resulted in one death and many injuries.

Poster of the Quat’Z’Arts ball in 1901, work by Ricardo Flores. Photo credit © Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Bal des Quat’z’Arts was named for the four traditional arts – architecture, painting, sculpture and engraving – and this was only the second year it was held. At the Moulin Rouge students set up elaborate tableaux where their model friends acted out the roles of historical and mythological characters. They used the rhetoric of “high art” to justify any decadence that might ensue.

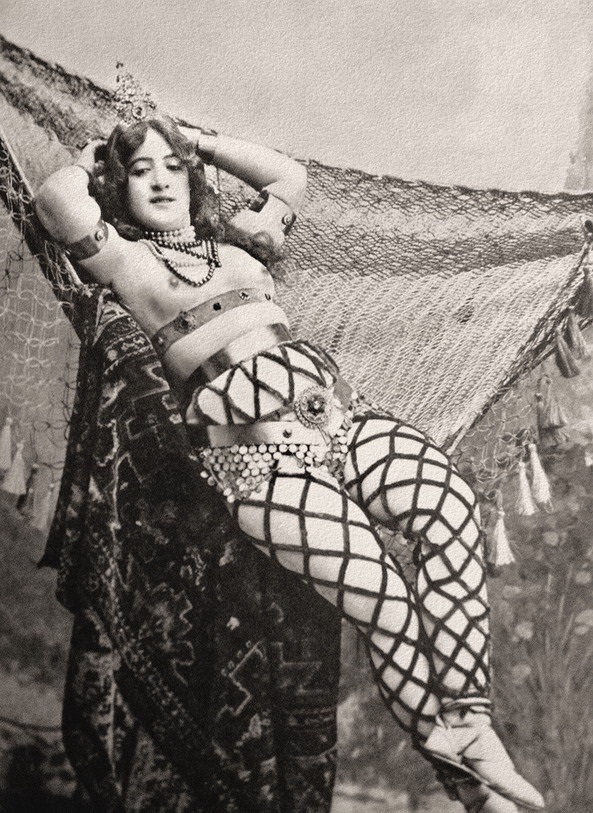

Sarah Brown’s near-nude representation of Cleopatra caused a stir, attracting the curious from throughout the city. Brown, three other models and one organizer were arrested and fined, but the trouble had only just begun. A crowd of Left Bank protestors gathered, comprised of students and simpatico workers’ organizations. When a gendarme volleyed an ashtray back to the crowd, it dealt Antoine Felix Nugent a fatal blow in the head. Rioters filled the streets for four days. It was a violent uprising that aimed to take control of the city. Twenty-thousand troops were deployed to quell the unrest. The police had lost control.

Sarah Brown, dressed as Cleopatra. Author unknown. Public domain.

It was against this backdrop that Louis Lépine succeeded to the Prefecture of Police. Using skillful and clever strategy, Lépine allowed various factions to march through Paris, but effectively kept apart, arriving at the planned rendezvous in stages. In the years following this, there were no deaths due to rioting during his almost 20-year tenure. It was impossible to avoid injuries but Lépine ensured that the army and guards of the Republic never met with demonstrators. The Bal des Quat’z’Arts was allowed to flourish without fear of future interference from the authorities.

Paris Crime Scene Investigations

Lépine is credited with overhauling and modernizing French policing. He took control of a corrupt force – one at very low point. The trust between the police and the public had been eroded. If this trust was not regained Lépine recognized that the city would once again have to relinquish itself to a very undesirable military state.

Louis Lépine & Georges Clémenceau 1908. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Lépine carefully set an agenda of reform from the ground up. He improved the professional quality of the Paris police force with the introduction of promotions and examinations in the areas of forgery and criminal psychology. He codified police procedures and regulations, updated the force’s equipment and tactics, and introduced forensic science into investigative work – it was during his tenure that fingerprinting was established as a means of identification.

Lépine was the first to organize regular police patrols and also created the Seine River police brigade and police bicycle units armed with whistles and truncheons. In a day without access to a phone in every home, he installed 500 telephone boxes to alert the fire brigades. He also reorganized traffic flow throughout the city. He insisted on a greater standard of politeness, especially toward women. Undercover work ensured the police arrived before the trouble did.

Paris flood. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Lépine was a man of many hats, and most likely Wellington boots. In late January 1910, the Seine, swollen due to months of torrential rain and faulty flood management, had peaked to 20 feet above its usual level – the highest the river had measured in 250 years. The differentiation between Left and Right bank had been erased with murky, debris-strewn water which turned streets into canals and public squares in lagoons. Flood waters rendered entire sections of the city impassible. Residents were trapped, telegraph lines toppled, and metro and surface trains were useless.

The intrepid Lépine’s responsibilities as Paris’s Prefect of Police now included street and river traffic, train schedules, fire-management, communications, and the supply of food. He managed public health concerns – the specter of typhoid haunted the city. The flood also gave rise to looting, street violence and food shortages. Fortunately, Lépine was just the man to handle these crises. He was endowed with a military sense of discipline, stoicism and courage, but also with an earnest desire to keep Parisians safe.

Paris flooding. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Don’t Cry for Me, Mona Lisa

The curator of the Louvre boasted that the Mona Lisa was unstealable. But one summer morning in 1911, a caricaturist intent on satirizing the woman with the mysterious smile, set up his easel in front of the Mona Lisa, but she was gone – stolen away in the night. Louis Lépine took charge of the investigation, acting with his usual decisiveness. More than 100 policemen were ordered by Lépine to clear the museum. Inch by inch his police inspectors searched the miles of museum galleries, cellars and roofs. Lépine’s theory was that it was a disgruntled employee committing an act of sabotage or blackmail. He should have listened to his intuition.

His team interviewed all the museum staff including past employees. He ordered the museum to be closed for a week while forensic analysis was carried out. With the aid of Alfonse Bertillon, a figure considered the founder of modern forensic policing, they dusted the site for fingerprints, and found a mysterious print on the Mona Lisa’s discarded frame. With the scant evidence found at the scene, Lépine pieced together a reconstruction of the theft. But for all his efforts, Lépine had no leads. Parisians were in denial about La Joconde’s disappearance. They paid their respects to the empty space like mourners at a funeral. Everyone thought that she was lost forever.

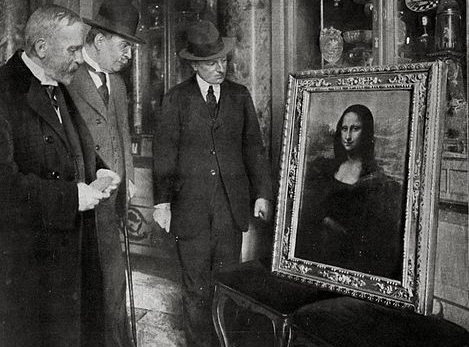

The Mona Lisa on display in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

General consensus was a gang of thieves must have made away with the work, but to resell the Mona Lisa was a fool’s game. The crime was ultimately solved more than two years later when a suspicious responder – code name Leonardo – answered a prominent Florentine art dealer’s advertisement “that he would pay generously for fine artwork.” The thief was Vincent Peruggia, an Italian who thought the masterpiece should be returned to its homeland. Peruggia had in fact been working in the Louvre and helped to make the special frame on which Bertillon found the fingerprint. The array of overlooked clues that Peruggia left behind dented Lépine’s great reputation.

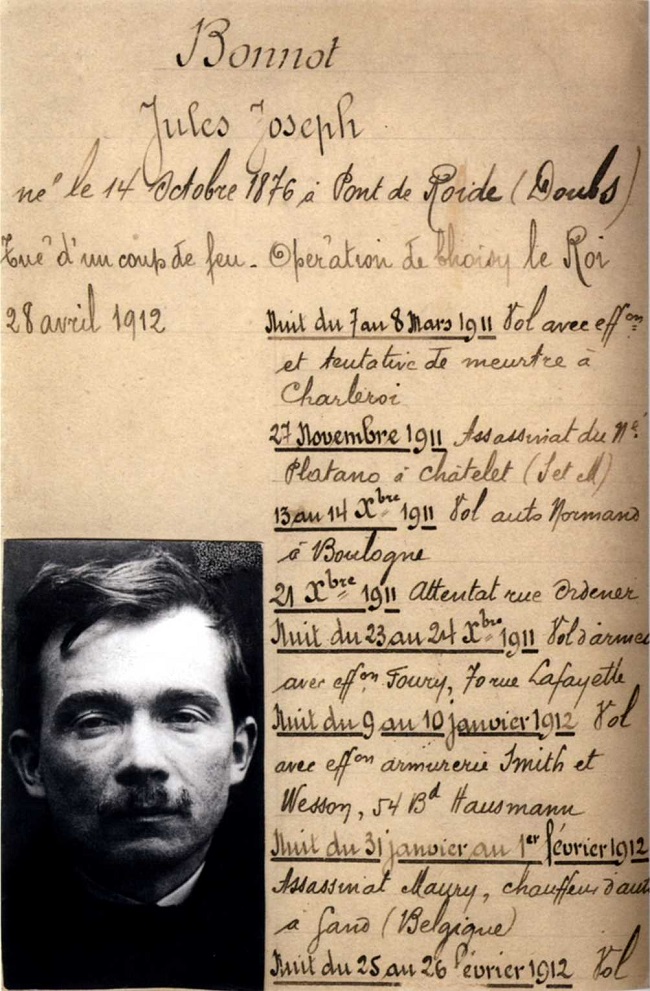

The Bonnot Gang

Lépine stated that “the criminals in Paris are numbered in their thousands.” Many of the criminals shaking Lépine’s world were what were then called Illegalists – perhaps what we would call anarchists today. They had strong ideological motives behind their actions and raged against government interventions. One such political activist was a skilled mechanic named Bonnot. His reputation as an agitator closed many doors to him. He tried his hand for a time in England, winning the position of Arthur Conan Doyle’s chauffeur. Back in France he was intent on carrying out his anarchist plots and appropriated large sums of money for his cause, killing civilians and police in his wake.

Bonnot. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

At the headquarters of l’Anarchie magazine he accumulated a gang of followers. They carried out their robberies using large, flashy getaway cars – the first crooks to do so. In April of 1912, Paris police narrowed down the whereabouts of France’s most wanted criminal ensuing in a lengthy armed siege. Bonnot was drawing up his will when Lépine decided to dynamite Bonnot’s hideout. Lépine was fearless and his mere presence seemed to calm the crowd. Lépine delivered the coup de grace.

In 1909 Lépine founded the Musée des Collections Historiques de la Préfecture de Police with pieces that had been assembled for the 1900 World’s Fair – l’Exposition Universelle. The museum concentrated on the forensics of policing and grew to contain evidence, photographs, letters, and memorabilia that reflects France’s famous criminal cases, characters, and conspiracies. It also contains many notable historical documents including the arrest orders of Charlotte Corday and the poisonous recipes of Landru. Visit the museum where it’s now located on the 3rd floor at 4 Rue de la Montagne Sainte Geneviève in the Latin Quarter.

Concours Lépine. Photo credit © Wikipedia, Public Domain

The Exposition Universelle also provided the impetus for Lépine to create a competition for inventors. Created in 1901, the Concours Lépine was originally intended to stimulate French invention and battle against imports. It first featured small French toy and hardware manufacturers but over the years it has grown into an annual event that includes a multitude of innovative ideas and is synonymous with audacity in invention.

We have the Concours Lépine to thank for the ballpoint pen, contact lenses, the Moulinex and the steam iron. The fair is held annually to this day, most recently at the site of the Concours’ premier, the Foire de Paris, Porte de Versailles.

Louis Lépine’s name also adorns the square adjoining the headquarters of the Prefecture of Police on the Île de la Cité. Place Louis Lépine is where the lush Paris flower market is held seven day a week.

Lead photo credit : The return of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. Photo credit © Wikipedia

More in crime, Floods, Louis Lepine, mona lisa, Riots

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY