Giacometti and Beckett: Existential Expats in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Alberto Giacometti was one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. Samuel Beckett was one of the century’s most influential playwrights. They were an unlikely pair, but as expatriates in 1930s Paris, not only did they share mutual friends within Paris’s Surrealist and Existentialist circles, but they also shared the same philosophical viewpoints. The friendship between the Swiss artist and the Irish writer slowly grew into an enduring one that lasted almost 30 years.

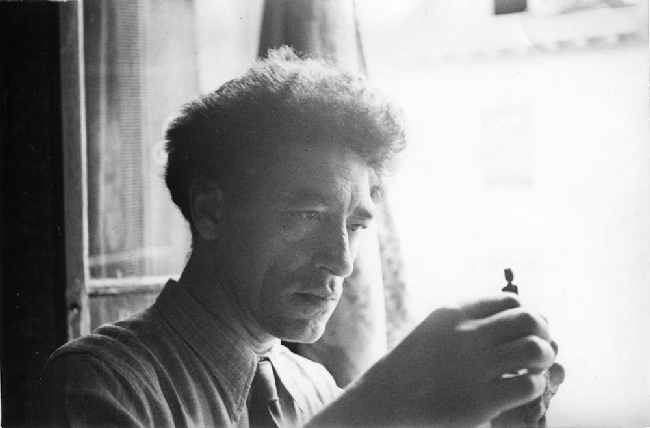

Giacometti 1944 Photo – Eli Lotar, Collection Fondation Giacometti,(c) Succession Giacometti Fondation Giacometti, Paris et ADAGP, Paris

Since adolescence, Alberto Giacometti had been a very capable sculptor: his lean and distorted statues are what he’s renowned for. His art was influenced by artistic movements such as Cubism and Surrealism. His philosophical questions about the human condition led him to be compared to the literary Existentialists.

Born in Switzerland in 1901, Giacometti was precociously artistic and was encouraged by his father and grandfather, both artists themselves.

Giacometti working on the plaster sculpture for L’homme qui marche – The Walking Man 1958 – the Tate

Alberto Giacometti arrived in Paris in January of 1922 to study sculpture. Until 1926, he regularly attended classes by the famed sculptor Emile-Antoine Bourdelle at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Giacometti moved to his Montparnasse studio in December 1926. The door was always open to his fabled workspace and he would maintain his studio for the rest of his life. Giacometti soon became popular among the Paris avant-garde. In 1929, he met Jean Cocteau and soon ran in the same circles as the Surrealists. Giacometti was best man at André Breton’s wedding.

The two-dimensional angularity of ancient Egyptian art was Giacometti’s source for the stylized striders he sculpted. His first twig-like sculptures made between 1938 and 1944 were tiny, reaching only 7cm (2.75”). He made these matchstick men small enough to render them isolated and alone in a perspectival space. Giacometti was expelled from the Surrealists in 1935 when the new life-like human heads he had created were deemed too real for Surrealist aims.

Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture “Walking Man” at UNESCO. Photo: Andy Quan

Post World War II, Giacometti created his most famous sculptures. As tall and thin as a late-afternoon shadow, Giacometti’s scarred metal wraiths reflected the psyche of post-war Paris. An essay on his art by the French existentialist writer Jean-Paul Sartre described Giacometti as having an Existentialist worldview. Giacometti enjoyed a rapid rise to fame and was a legendary figure for the post-war generation.

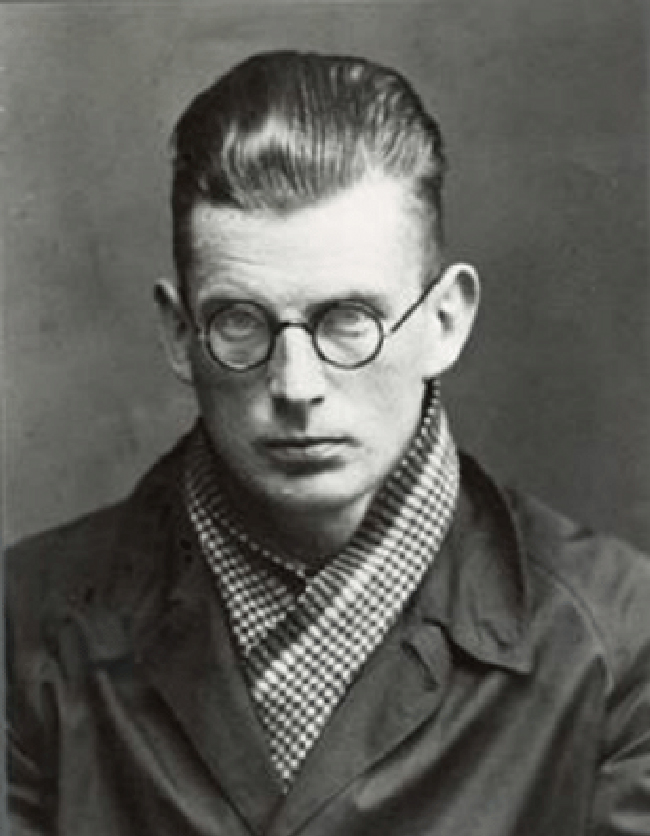

Samuel Beckett, born in a Dublin suburb in 1906, was an author, critic and playwright. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969 and today is best known for his play, Waiting for Godot.

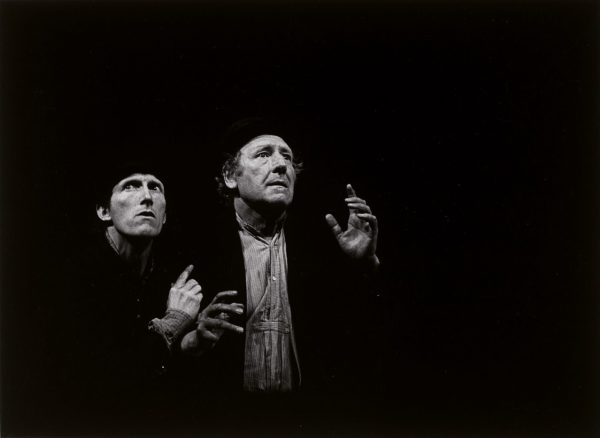

Waiting for Godot, text by Samuel Beckett, staging by Otomar Krejca. Avignon Festival, 1978. Rufus (Estragon) and Georges Wilson (Vladimir) / photograph by Fernand Michaud.

In 1927, Beckett graduated from Trinity College, Dublin. With a bachelor’s degree under his belt, Beckett moved to Paris at age 21 to teach English at the École Normale Supérieure. There he joined the circle of the self-exiled Irish writer James Joyce. Beckett returned to Ireland in 1930, but after four terms lecturing at his alma mater, he began a nomadic existence, traveling restlessly throughout Europe before settling permanently in Paris in 1937. Beckett was soon a known face in and around the Left Bank cafés. Although Beckett was a prolific writer before the war – composing short stories, poems, reviews, and essays on James Joyce and Marcel Proust – relatively few of his early works were published.

Photograph of Samuel Beckett as a student in the 1920s, Public Domain

As a citizen of Ireland, a country neutral during World War II, Beckett was allowed to remain in France after the occupation of Paris by the Nazis, stating, “I preferred France in war to Ireland at peace.” With his partner, he joined an underground resistance group in 1941 and translated secret Axis reports. They fled to France’s unoccupied zone, walking south for over six weeks to Avignon when the Gestapo was at their heels. In 1945, Beckett volunteered in the building of a military hospital in Saint-Lô, Normandy. Beckett was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his work with the French Resistance.

The period following World War II was Beckett’s most productive, writing more short prose and a trilogy of novels. His most famous play, Waiting for Godot, was staged in January of 1953 at the small Théâtre de Babylone in Paris.

“I think; therefore, I am,” the words of Descartes, Beckett’s favorite philosopher, rang in his mind as he tried to capture the essence of being for the play’s two characters, Vladimir and Estragon. Projecting a befuddled – Why am I here? – the two characters standing by a tree stripped bare were an allegory for the pointlessness of life. Waiting for Godot was a success and Beckett rose to world fame.

The friendship between the sculptor Alberto Giacometti and the writer Samuel Beckett isn’t a widely known one, but it was an enduring one. They most likely met at the Café de Flore in the autumn of 1937, introduced by mutual friends. They were in the same orbit as other Existentialists but their first encounters were random and infrequent. Their friendship didn’t immediately take off. Beckett was prone to long, uncomfortable silences, whereas Giacometti was notoriously gabby. Their connection strengthened gradually, no doubt due to their shared artistic philosophies. It was inevitable they would become friends.

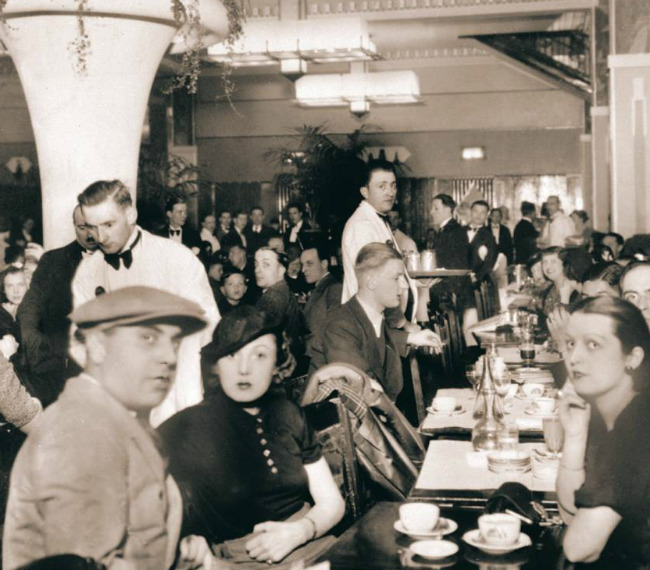

Café de Flore. Photo credit: Arnaud 25/ Public domain/ Wikimedia Commons

Though working in drastically different media, they strived to create a meaning for life materially through their respective works. Giacometti always continued to question his artistic path and searched for ways to challenge reality. Beckett’s characters embodied his search for life’s meaning.

When Giacometti and Beckett first met, the playwright was boarding at the Hôtel Libéria, a favorite of the local artists now known as Hôtel a la Villa des Artistes at 9 Rue de la Grande Chaumière. Located down a narrow alleyway, Giacometti’s studio and home at 46 Rue Hippolyte-Maindron (in Montparnasse) was a 20-minute walk from Beckett’s accommodation. At night, the two would meet in one of the Parisian cafés – the Café de Flore, Le Dôme or La Coupole – to drink and socialize with the intelligentsia of the period, other artists and thinkers, such as philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean Genet.

A historic scene at La Coupole, the famous brasserie. Photo: La Coupole

The pair would often leave the cafés in the wee hours of the morning and ramble around the city together. They frequently discussed each other’s work during their nocturnal strolls. Research undeniably proves that Beckett and Giacometti’s nights routinely concluded with a visit to a brothel – their favorite being the legendary Sphinx located behind Gare Montparnasse – where one could have an enjoyable evening without always having to pay for a room.

Walking through Paris at night had its perils. On 12 January 1938, Beckett was almost fatally stabbed in his lung by a pimp on the Avenue Général Leclerc. While recovering in the hospital, Beckett met Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, a piano student who would become his life-long companion.

On 11 October of the same year, while Giacometti stood at the Place des Pyramides, the sculptor was knocked down by a vehicle operated by a drunken American heiress, who crashed into a shop window leaving Giacometti unconscious on the pavement with a crushed foot.

Giacometti had a limp for the rest of his life and Beckett had trouble breathing because of these unfortunate late night encounters. Wandering through the streets at night, this weatherworn duo resembled Beckett’s most famous characters. The two heroes of Waiting for Godot, Vladimir and Estragon, erroneously referred to as tramps are merely two human beings, like Giacometti and Beckett, questioning what they were there for.

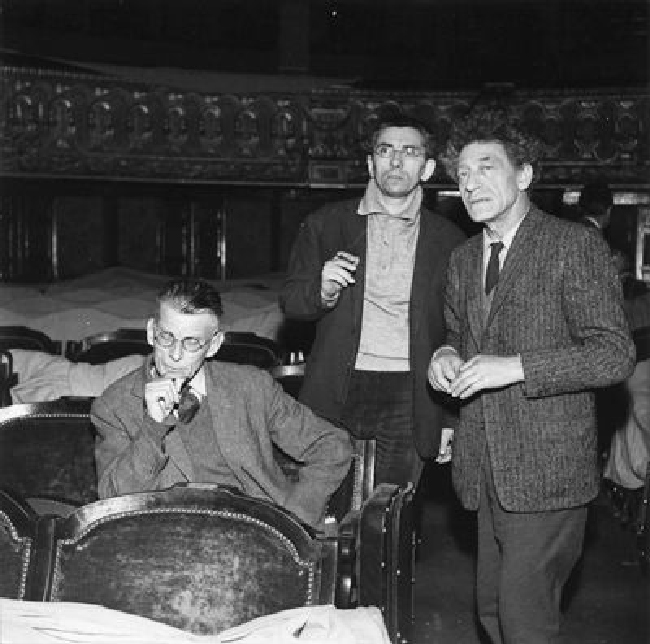

Boris Lipnitzki Samuel Beckett, Jean-Marie Serreau and Alberto Giacometti assisting at a rehearsal of Waiting for Godot, Théâtre de l’Odéon, Paris 1961

Yet, one night a prostitute who saw them sitting on a café terrace felt compelled to go inside and tell the proprietor, “It’s your luck to have two of the great men of our time sitting together on your terrace, and I thought you ought to know it.”

Giacometti spent the war years in Geneva where he met Annette Arm, the woman who would become his wife. She joined him in Paris in 1946. Beckett was exiled in the south of France with his partner and fellow resistance fighter Suzanne. In 1945, the two artists returned to Paris and their relationship grew closer. Beckett deliberately took an apartment on the Rue des Favorites, choosing to stay close to the cafés and Giacometti’s studio. This period from 1945 – 1960, when they maintained their closest contact, is also the time in which both artists produced many of their most celebrated works.

National Gallery of Ireland credit Alexander Liberman, Alberto et Annette Giacometti dans d’Atelier, 1951. © J. Paul Getty Trust

Giacometti sat in the audience of Beckett’s original 1953 production of Godot at the Théâtre de Babylone, a theater converted from a shop. In May of 1961, Estragon and Vladimir were again waiting for Godot to arrive. Beckett was now world famous. No longer was their stage a makeshift locale, but the Odéon in Paris. His steadfast friend Giacometti was also renowned by this time.

The scenery for this production of Godot was stark – a single tree – which Beckett entreated his friend Giacometti to create for him. Giacometti had retained his Surrealist taste for the absurd and readily accepted. His final design consisted of a single plaster tree, in pure Giacometti-style. Reportedly, Giacometti and Beckett’s iconic tree was destroyed during the May 1968 Paris Riots by students occupying the Odéon. A freely-made choice that the duo might have looked upon with favor.

L’Odeon Theatre. Photo: Marilyn Brouwer

At the age of 64, Alberto Giacometti died from heart disease in Chur, Switzerland and was buried in his home town of Borgonovo. Samuel Beckett grieved his friend’s death. “Giacometti dead?” he wrote in January of 1966, “take me off to Père Lachaise jumping all the red lights.” Beckett wanted to be buried on the spot.

Beckett continued to live in the Paris area until 1989, doing most of his writing in a small, secluded house in the Marne valley. He shunned publicity and in 1969 when he received the Nobel Prize for Literature, he accepted the award but declined the trip to Stockholm to avoid the public speech at the ceremonies. Beckett died in 1989 and was buried in Montparnasse cemetery.

Montparnasse cemetery © Meredith Mullins

Throughout their careers, both Giacometti and Beckett were concerned with the nature of human existence. Their thoughts were as deep and profound as their friendship.

Lead photo credit : Giacometti and Samuel Beckett in Giacometti's studio 1961, Public Domain

More in Alberto Giacometti, Beckett, Giacometti, Parisian history, Samuel Beckett

REPLY

REPLY