Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The playwright Samuel Barclay Beckett was born in Ireland in Dublin on April 13th, 1906. He was to spend most of his life in Paris, doing most of his writing in French, before translating it himself back into English, but Samuel Beckett was to remain forever Irish, complex, black humored and not averse to a drink or three.

His education at the prestigious Trinity College Dublin– where he studied French, Italian and English and was elected a Scholar in Modern Languages– enabled him in 1928 to take up the post of lecteur d’anglais at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris for the next two years. This period was to prove a pivotal point in Beckett’s future. Beckett was perhaps unusual as his brilliant intellect went hand in hand with his physical prowess. Not only an accomplished golfer, Beckett also excelled in cricket as a left-handed batsman and a left-arm medium paced bowler.

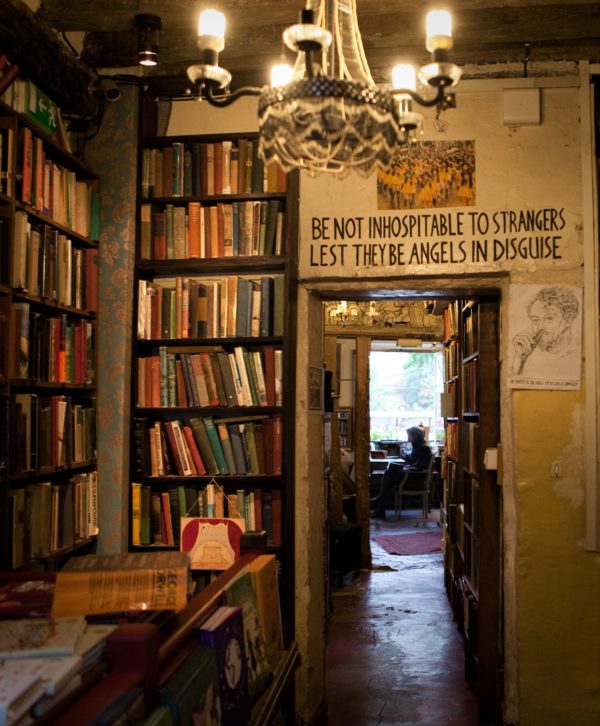

Beckett was introduced to James Joyce by his close friend, the poet Thomas MacGreevy, and the young Beckett fell under his spell. Like others before and after him, Beckett was only too eager to assist Joyce in any way possible and began the research, for what was to become Joyce’s acclaimed novel, Finnegans Wake. Joyce introduced Beckett to Adrienne Monnaie’s book shop in Rue de L’Odeon and thence to Sylvia Beech’s Shakespeare and Co, and also showed him his favorite bars in Paris (often frequented nightly). Beckett was adept at helping Joyce home after a particularly heavy session. Beckett himself was not averse to a drink and frequented the Cochon de Lait in the Rue Corneille.

Shakespeare and Company, Entrance to Reading Library, 2015. Image credit: (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Paris in the 1920s was a fertile cultural ground for artists of all persuasions, be they writers, artists, poets, filmmakers or entertainers. ‘Les Années folles’– as well as producing the likes of Josephine Baker and Mistinguett– drew together painters of astonishing talent, including Picasso, Chagall, Mondrian, Bonnard, Matisse, Dali and Miro. Writers were an obvious addition to this heady mix and Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Edith Wharton and T.S. Eliot all made Paris their home. Montparnasse was literally bursting at the seams with all the brightest shining lights of the time.

Beckett began writing but later acknowledged that his first works were too influenced by Joyce’s style. Beckett had become very close to Joyce’s family by now, but the result had detrimental and unintended consequences. Joyce’s daughter Lucia, a professional dancer, with the undiagnosed signs of schizophrenia, had decided she was in love with Beckett who did not reciprocate her feelings and rejected her.

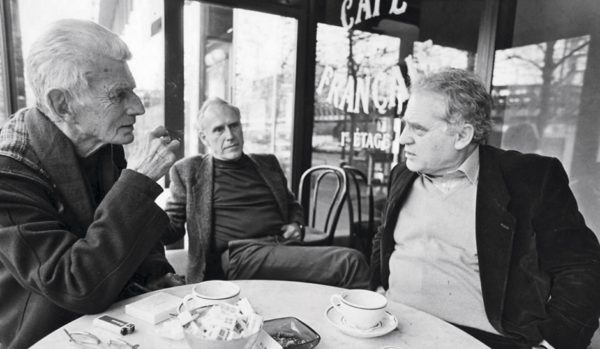

Jack Garfein with Samuel Beckett & his editor Barney Rosset in Paris in the 1960s. Image credit: PMPProd (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Joyce, for whom Lucia was his beloved muse, never wanting to acknowledge his daughter’s mental fragility, blamed Beckett for Lucia’s distress and their relationship cooled. Whether this influenced Beckett’s departure from Paris or not, he returned to Trinity College as a lecturer in 1930. By 1931, Beckett’s very brief, academic career had ended and he began writing in earnest: poems, critical essays, short stories, and finally in 1932 his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women. (This failed to get published until 1992, three years after Beckett’s death.)

Beckett spent the next five years between Germany and Ireland. He was disturbed by the underlying atmosphere and the inexorable rise of Nazism in Germany. His father’s death in the family home Dublin in 1933 had an enormous effect on Beckett and doubtless affected his future writing. Family life in his childhood home with his mother proved to be too fraught for Beckett and in 1937 he returned to Paris with the famous quote, ‘Nothing changes the relief at being back here.’ Beckett rented an apartment back in the 6th arrondissement at 12, rue de la Grande chaumière.

The quote still held true for Beckett a year later, despite being stabbed by a pimp whose advances he’d rejected, the injury serious enough for him to be hospitalized. Beckett refused to press charges, being quite taken by the pimp’s name, Prudence. It was while recovering in hospital that Beckett was visited by Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil who would later become his wife more than 20 years later. The intervening and subsequent years were interspersed with numerous affairs.

Beckett’s first novel, Murphy, was published in 1938. It was written in what was to be Beckett’s trademark style: bleak, minimalist, filled with gallows humor and black comedy, known with perfect accuracy, the Theatre of the Absurd, and uniquely Samuel Beckett.

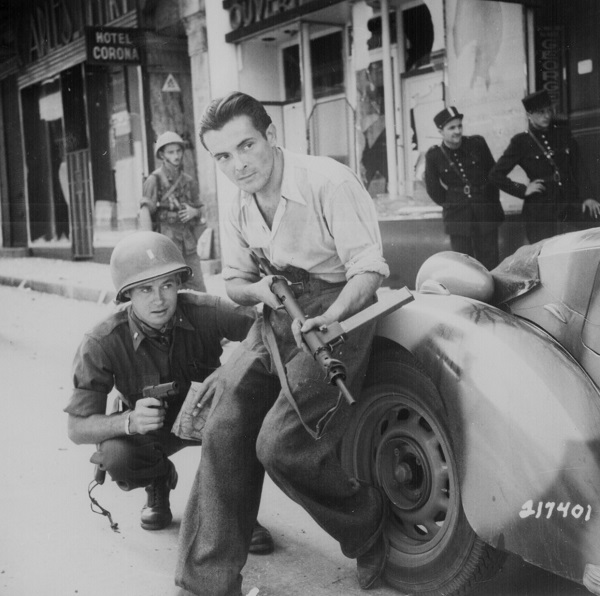

American troops parade the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, after the Liberation of Paris, in the ‘Victory’ Parade’. August 1944. Image credit: Wikipedia, public domain

But war was on the horizon and Beckett, with an Irish passport in Europe, was in an invidious position. However he had no intention of staying in neutral Ireland during a war against the Nazis who Beckett had found so repulsive during his time in Germany. Instead he returned to Paris and joined a small resistance movement in Paris. The network was called GLORIA SMH and worked in conjunction with the Special Operation Executive. Beckett, along with Suzanne, translated intelligence reports which were then transcribed onto microfilm and smuggled to London. In 1942, their network was betrayed by a priest and Beckett and Dumnesil escaped. Ten minutes later and their fate would have been in the hands of the Gestapo who were in close pursuit. Many of their cell were captured and sent to concentration camps. Many did not survive, causing Beckett intense grief. Beckett and Dumnesil then walked for six weeks through France before hiding out near Avignon. They still did whatever they could for the resistance but Beckett was in constant danger of being informed on. Although he spoke fluent French, he still retained an Irish accent and collaborateurs were not rare in Vichy France. It was a period in Beckett’s life he rarely spoke of despite being awarded the Croix de Guerre by General de Gaulle and the La médaille de la Reconnaissance française. Despite the dangers and the hardships of living in the Vaucluse at this terrible time, the seeds of Waiting For Godot were growing.

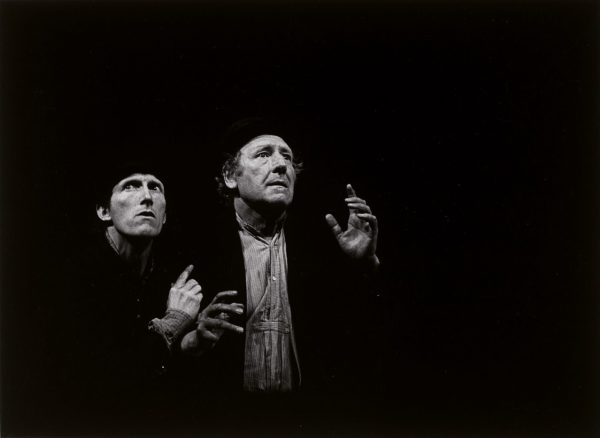

When the war ended, Beckett returned to Ireland for six weeks to see his ailing mother. It was here, watching crashing waves, that Beckett had a sort of epiphany and decided to write all of his future works in French to distill his use of language. Waiting for Godot was the result and had its first showing in the Babylone Theatre in Paris in 1952. There had never been anything like it and there was no turning back for Beckett. His two tramps waiting around for Godot had captured the imagination further afield than France and Beckett was persuaded to translate the play into English. Waiting for Godot revolutionized post war theatre. It was first performed in London in 1955. More than 60 years later the play is in still in constant production and still much loved by actors, producers and audiences.

Staged photo of an American officer and a French partisan crouching behind an auto during a street fight in a French city, ca. 1944. 111-SC-217401. Image credit; Wikipedia, Public Domain

Beckett has been described as a lonely genius, intransigent and solitary, suggesting Beckett was unapproachable, a misogynist even, but there was so much more to Beckett than a tortured writer. He married Suzanne Deschevaux Dumnesil in 1961. By now living in 38, Boulevard St Jacques, each with their own bedroom and separate entrances, Beckett continued his affairs and his long term relationship with Barbara Bray. He gambled at the Salle Wagram in the 17th arrondissement, played billiards in Les Trois Mousquetairs in Montparnasse and drank at the Falstaff and the Closerie des Lilas or in a little bar in Rue St Jacques.

His bleak humor hid a warm, compassionate man who was known as much for his kindness as his austere persona. Harold Pinter, the renowned British playwright, recounts an evening out with Beckett in Paris. Beckett had driven in his little car at great speed from bar to bar ending up in Les Halles. Pinter, after a surfeit of alcohol and onion soup, was feeling more than the worse for wear with unbearable indigestion and heartburn. Finally he had laid down on a table. Waking up a little later, he found he was alone in the restaurant. Some time later Beckett appeared with a tin of Andrews Liver Salts he’d driven around Paris at 4am to buy for Pinter.

Billie Whitelaw, the renowned British actress who appeared in several of Beckett’s plays, notably, ‘Not I‘, adored Beckett and remembers her first meeting with Beckett as a shy man with pale blue eyes and disheveled hair and a kind face. ‘Not I‘ was a play where Whitelaw was strapped into a chair and masked with a black hood and blackened face, only her mouth on view. It was a 16 minute monologue which affected Whitelaw deeply.

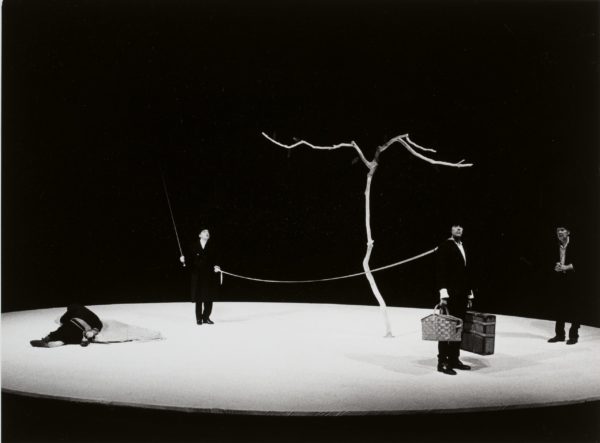

Waiting for Godot, text by Samuel Beckett, staging by Otomar Krejca. Avignon Festival, 1978. Rufus (Estragon) and Georges Wilson (Vladimir) / photographs by Fernand Michaud. Image credit: Fernand Michaud (CC0)

After the success of Waiting for Godot, Beckett wrote Watt, 1953, Endgame 1957, Krapp’s Last Tape, 1958. Happy Days, 1961, Ohio impromptu 1981. All this alongside his short stories, prose and poetry and The Theatrical Notebooks which somehow fitted in with Beckett himself directing all his major plays performed in London, Paris and Berlin. Beckett envisaged the staging of all his plays presenting solutions to practical problems. Where his work was concerned, there is no argument that Beckett was obsessed with the detail, overseeing productions and taking copious notes.

But this was the same man who drank with his countryman Peter O’Toole (an actor famed for his capacity for drink) and ‘wailed’ at the novelist Edna O’Brien’s piano. Sian Phillips, the actress wife of Peter O’Toole, described him as a “beautiful bird of prey, incredibly handsome, a merciless God.” She said she knew she was in the presence of a ‘great man’ and that working with Sam was one of the best things that ever happened to her. Although insisting that his way of getting things done was “the only way, he was never anything but courteous, and he wasn’t a bully.” This description of Beckett is repeated in similar form by almost everyone who ever worked with him or indeed knew him outside the theater.

In 1969 Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his writing, which-in new forms for the novel and drama-in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation.’

Samuel Beckett died in Paris on December 22nd, 1989.

He is buried in Montparnasse Cemetery. The greatest writer of the 20th century.

Purchase his famous work on Amazon below:

Lead photo credit : En attendant Godot, 1978 Festival d'Avignon, directed by Otomar Krejča. Image credit: Fernand Michaud (CC0 1.0)

REPLY

REPLY